Explosive Growth and World Domination

(1971-1980)

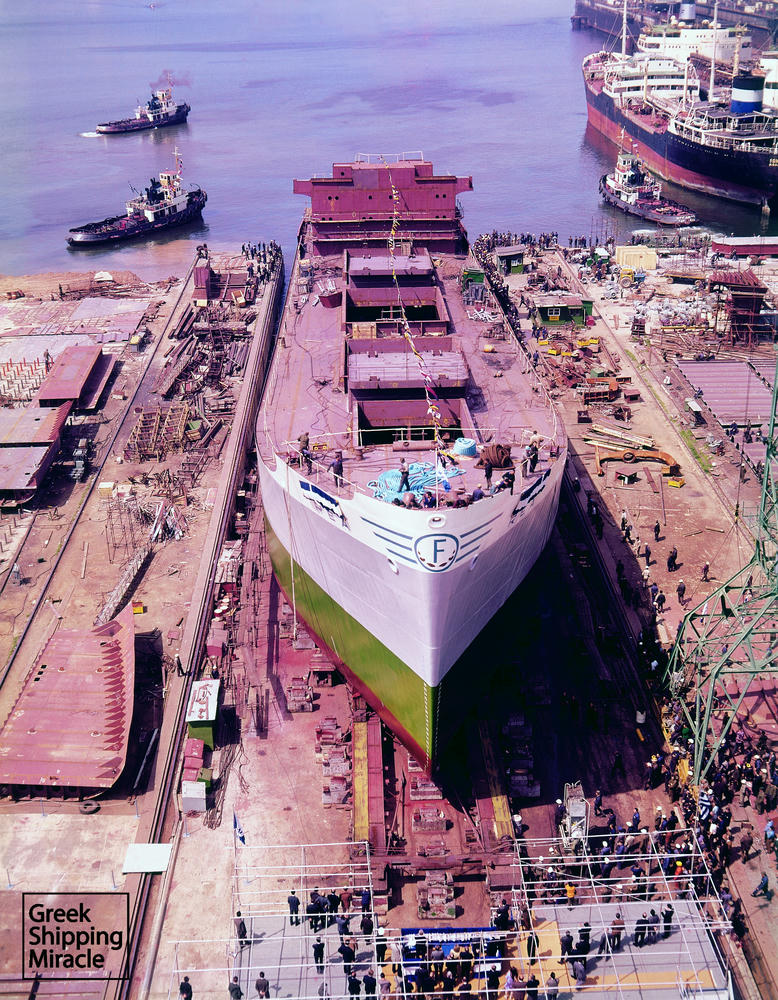

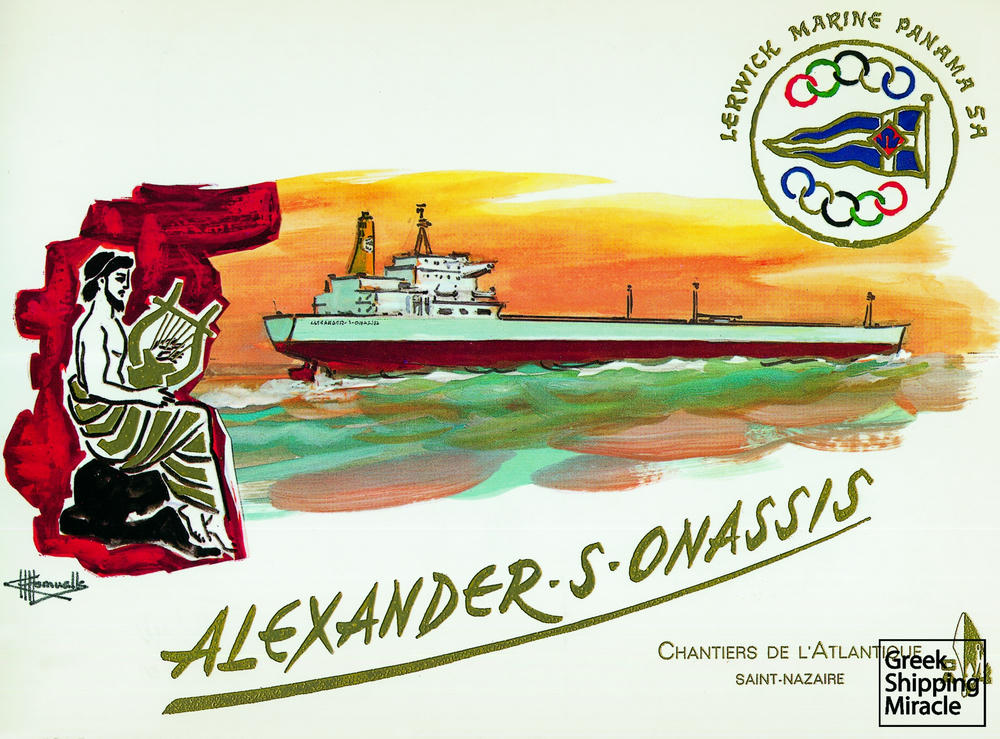

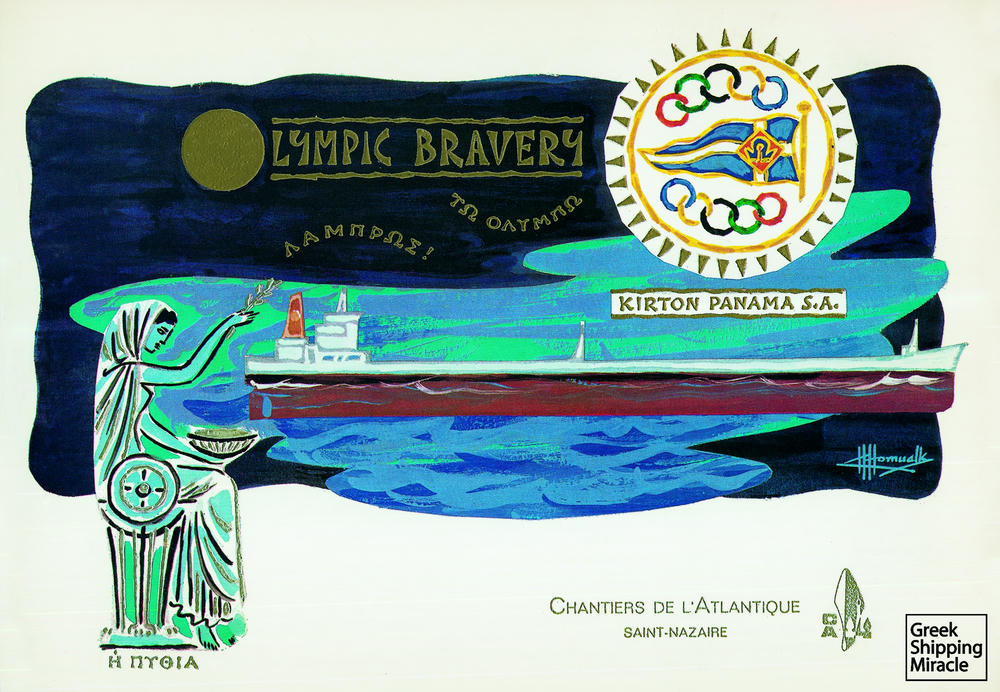

At the beginning of the 1970’s, the freight market started weakening, causing worries that shipping was once again in danger of facing a period of recession. Despite this, Greek shipowners continued investing, both in second-hand acquisitions as well as in the construction of ships, especially in Japan, where the vast majority of Greek-owned newbuildings were built since the middle of the previous decade.

The colonels’ regime was at the time striving to boost the Greek registry, while the simultaneous establishment of approximately 300 shipping enterprises, operating offices under the special legislation introduced in 1967, led to the rapid transformation of Piraeus into an important shipping centre of international character.

However, the policies adopted had, beyond obvious positive results, their negative side. The almost uncontrolled flow into the industry, led to many opportunists becoming active in Greek shipping. The performance of several new entrants damaged the image of the industry in following years.

In August 1971, the regime unexpectedly abolished the administrative body of the shipping industry, in contrast to its policy over the past five years towards this important sector of the economy. The entire maritime activity was placed under another ministry dealing with various sectors, namely the Ministry for Shipping, Transport and Communications. This initiative deregulated any efforts for further strengthening of the Greek registry. Thus, despite the continuous growth of the national registry, almost half of the Greek-owned fleet was still sailing under foreign flags in 1972.

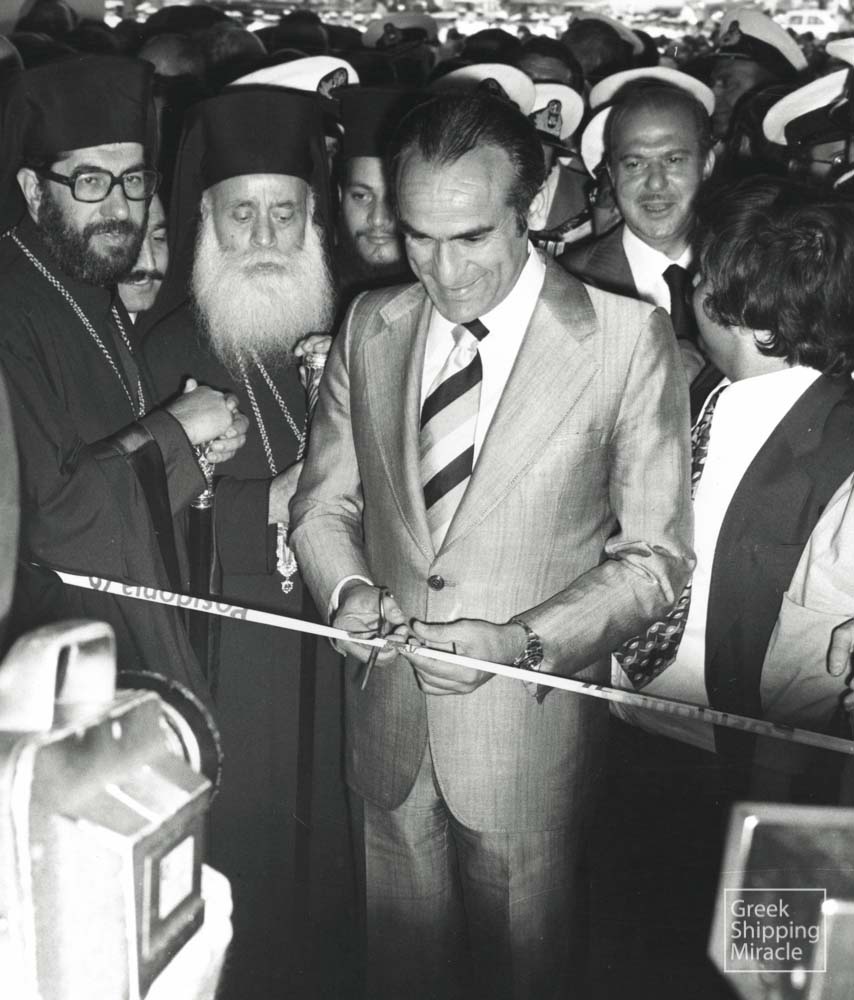

By mid-1973, after massive acquisitions of vessels of any type and size by Greek owners, the total registry entries exceeded 3,000 ships. This milestone was celebrated in a ceremony held in Piraeus. In September 1973, however, following the unsuccessful operations of the newly-established Ministry of Shipping Transport and Communications, an independent Ministry of Merchant Marine was re-established. A few weeks later, the regime of Georgios Papadopoulos collapsed following serious popular pressure and a new dictatorship, headed by a former partner of his, took power.

Meanwhile, world seaborne trade was in complete turmoil due to the developments in the Middle East. The severe oil crisis highlighted by the shortage of this invaluable product and the dramatic increase in its price affected the entire globe. The foundations of many powerful economies were jeopardised. Shipping, oil’s major transporter, continued operating for some months in a satisfactory but unstable freight market. During this period, Greek owners continued investing heavily, both in terms of second-hand acquisitions, as well as by placing newbuilding orders.

It did not take long for the market to collapse, reaching catastrophic dimensions. At the same time, Greece was experiencing challenging times. Following the dramatic events in Cyprus in July 1974, the dictatorship was collapsing. One of the devastating consequences of its rule was the standstill in the dynamic development of the Cypriot registry that had until the invasion of Famagusta by Turkish forces contributed decisively to the development of Cyprus.

After eleven years of self-exile in Paris, Constantine Karamanlis returned to Greece on 24 July 1974 to undertake the difficult task of restoring democracy and uplifting the morale of the people. Most Greeks were on his side, while the shipping industry rushed to offer its support to his efforts.

In a meeting attended by a large number of shipowners, held a month later, it was decided that each Greek ship was to contribute one US dollar per deadweight ton. Within a short period, 60 million dollars was raised and made available to the Greek government. The seafarers’ contribution was also surprising. They held fundraisers on board to collect money to assist the national effort.

In January 1975, Anthony Chandris, a renowned personality within the international maritime community, became the new president of the Greek Shipowner’s Union. Among the first issues that needed to be addressed was shipping’s public image at a time when democracy was being restored.

The previous regime had demonstrated an unprecedented interest in the shipping industry. This led many people to believe that the maritime community was in line with the colonels’ dictatorship. That perception was made even worse by some individual cases within the industry that were generalised by the media. Despite the fact that none of the traditional and prudent owners were involved in such actions, the image of Greek shipping industry was seriously damaged.

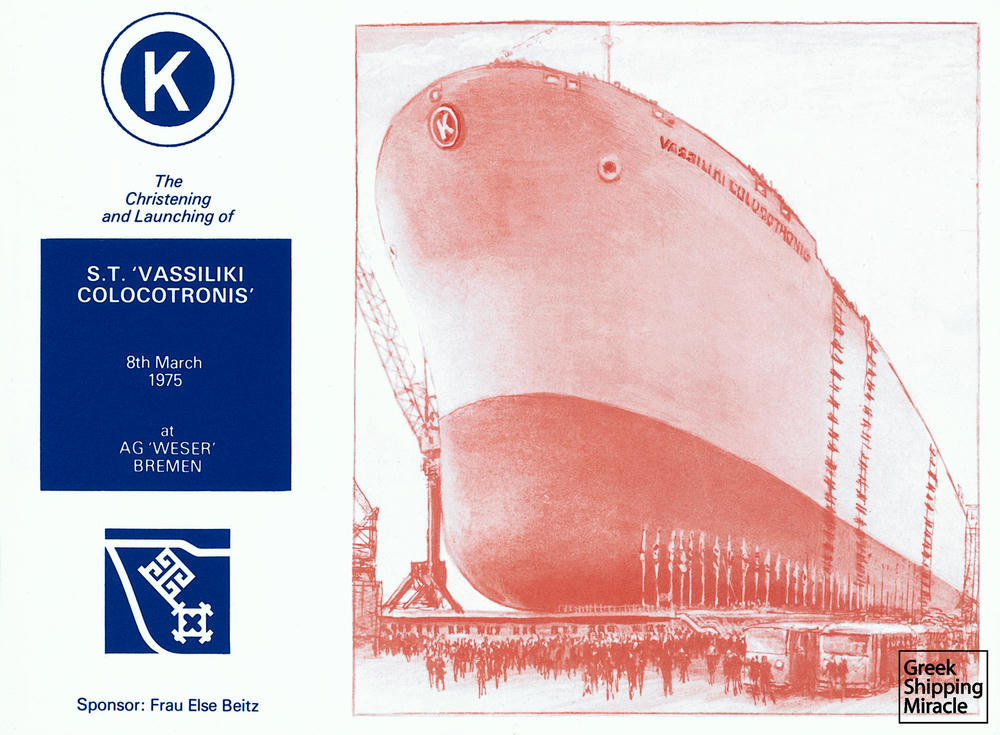

Facing a lot of pressure and serious problems at the time, the new government failed to deal with an issue dramatically undermining the role and importance of the industry. On the other hand, Karamanlis was well aware that his efforts to restore political and financial stability in the country would be based to a significant extent on the international prestige and the dynamic power of the sector whose performance only in newbuildings during that particular decade marked the delivery of 779 oceangoing vessels!

In terms of other issues concerning the industry at the time, the viewing of the Constitution by the government resulted in the introduction of tonnage tax, i.e. an annual levy based on the gross tonnage of each Greek-flag vessel. At the same time, there was serious concern over the government’s decision to nationalise the entire business activities of the Andreadis group in Greece, including Elefsis shipyards. This action, intensified at the time due to pressure exerted by trade unions opposing private enterprise, ultimately led to the complete disorganisation and collapse in the operation of the four major shipyards in Greece established by outstanding members of the Greek shipping community, namely Stavros Niarchos, Stratis Andreadis, N.J. Goulandris Sons and John C. Carras.

This new outlook also affected seafarers’ trade unions. The views expressed by several leaders of the 14 unions belonging to the Panhellenic Seamen’s Federation was a clear sign that the industry was entering an era highlighted by strong opposition between seafarers and shipowners. What made things worse was that shipping was also facing the side effects of yet another recession, forcing owners to cancel newbuilding orders at high cost, while a large number of them were not able to meet loan obligations, resulting in the collapse of many important enterprises in the coming years.

Despite the difficulties shipping encountered during this period, including crew shortage, the efforts to strengthen the registry continued unabated. Greek owners were determined to support efforts towards establishing the Greek flag as a leader in world seaborne trade. At the same time, they placed particular emphasis in enhancing relations with international maritime organizations in light of the impending imminent integration of Greece in the European Community.

Even though the industry had been in decline for some time, suffering significant losses, the improvement in the market during 1979 contributed to the Greek fleet topping the world list with a fleet close to 4,000 vessels. On 28 May 1979, Karamanlis signed the treaty marking Greece’s entrance into the wider European family. In his speech, he stressed Greece’s major contribution to Europe, the dynamic presence of Greeks in diaspora and its great shipping industry.

In order to make issues concerning an industry whose role was instrumental to the country’s growth widely known, the Union of Greek Shipowners organised a shipping conference on 8 December 1979. Speeches delivered both by members of the cabinet and shipowners’ representatives highlighted the industry’s capabilities. A few days later, Constantine Karamanlis requested from owners to intensify efforts to increase shipping’s foreign exchange inflow. The sharp rise in oil prices had dramatically affected the balance of payments in Greece. The response by shipowners in meeting the country’s needs was prompt, resulting in a sharp increase in foreign exchange inflow from shipping over the next year.

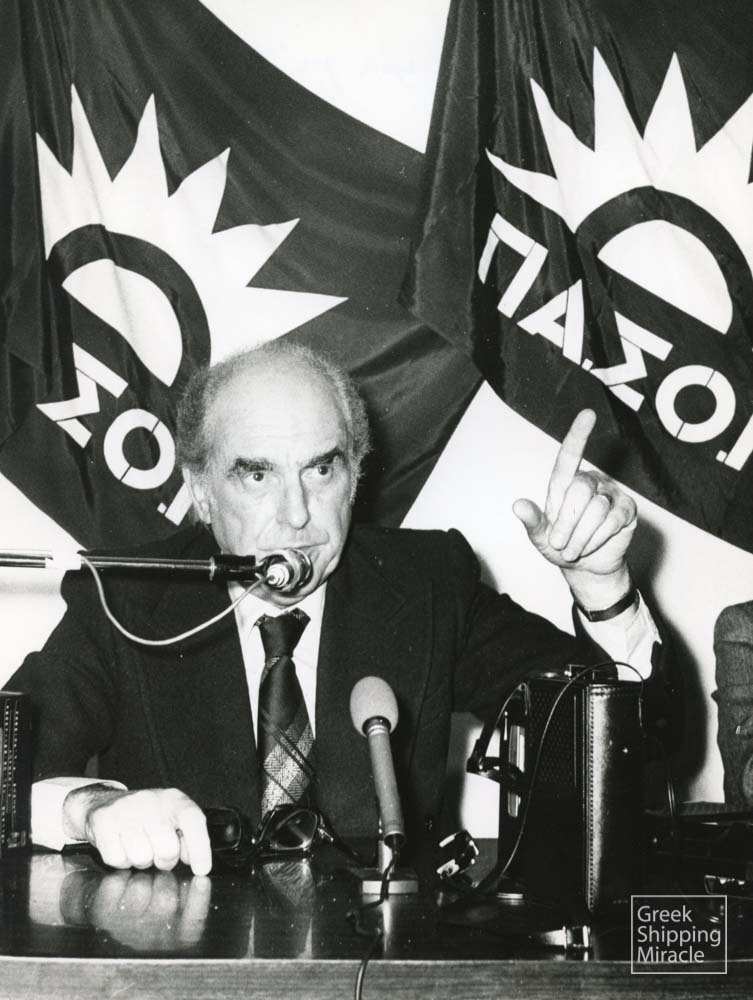

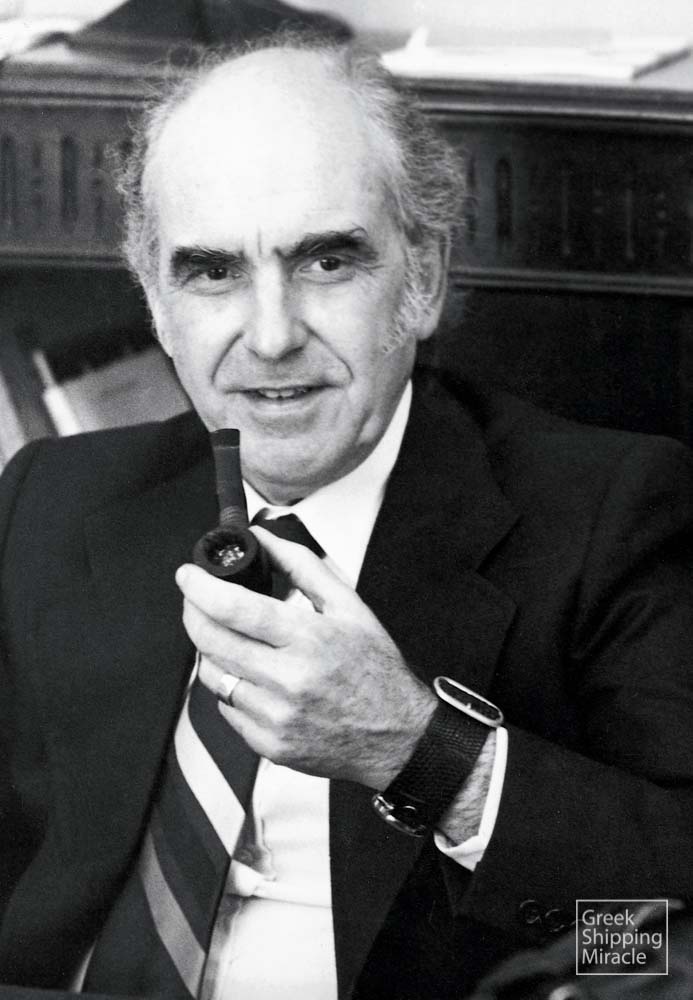

In July 1980 the Panhellenic Union of Merchant Marine Engineers called for a 48-hour strike. It was the first strike in the sector since 1948 and marked the beginning of industrial action adopted on a repeated basis over the next decade. That particular strike did not find much support among seafarers in oceangoing ships; however, it caused concern among shipowners, international financiers, as well as charterers of Greek-flag ships. At the same time, it was the herald of new mentality in addressing the industry’s issues, that was inevitably brought in by a politician who was fast coming onto the scene.