Change of Scene amid Deep Recession (1981-1990)

By 1981, Greece was a full member of the European Community. Its membership marked the addition of 3,942 ships to the European merchant fleet, doubling its size. The combined European merchant marine accounted for over a quarter of the global fleet, as Greece had just overtaken Japan and was only second to Liberia in world rankings.

At the time, market levels were still satisfactory and no one could predict the impending storm. A crisis that broke out shortly afterwards within the tanker market was a bad omen for the industry. Many owners began to realise it would not take long for the dry cargo sector to befall the same fate.

Whilst the shipping industry was preoccupied with the collapsing market, the popularity of the New Democracy government under Georgios Rallis was fast losing ground. At the same time, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) of Andreas Papandreou was steaming towards power, largely supported by working class people and most trade unions.

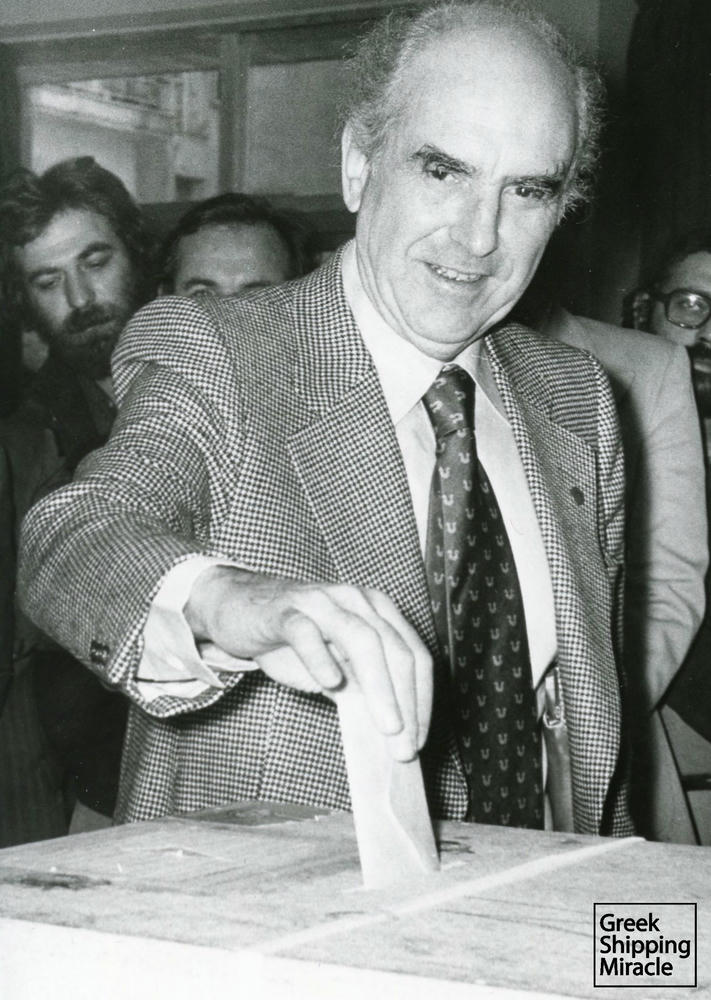

PASOK’s electoral dominance was confirmed in October 1981, with almost one in two Greeks voting for the socialist party. At this time, world seaborne trade began experiencing its most dramatic crisis since the Second World War.

The excessive growth in the world fleet during the previous decade, along with the unprecedented energy crisis, had a detrimental effect on very large crude oil carriers. Many of them were sold for scrap before they had even completed 15 years of operation. Soon, the crisis spread to the dry cargo market, resulting in massive lay-ups of vessels in various parts of Greece. It was not long before the scenes of lay-up sites in the country were reminiscent of mass decommissioned Liberty ships in rivers in the USA during the post-war period.

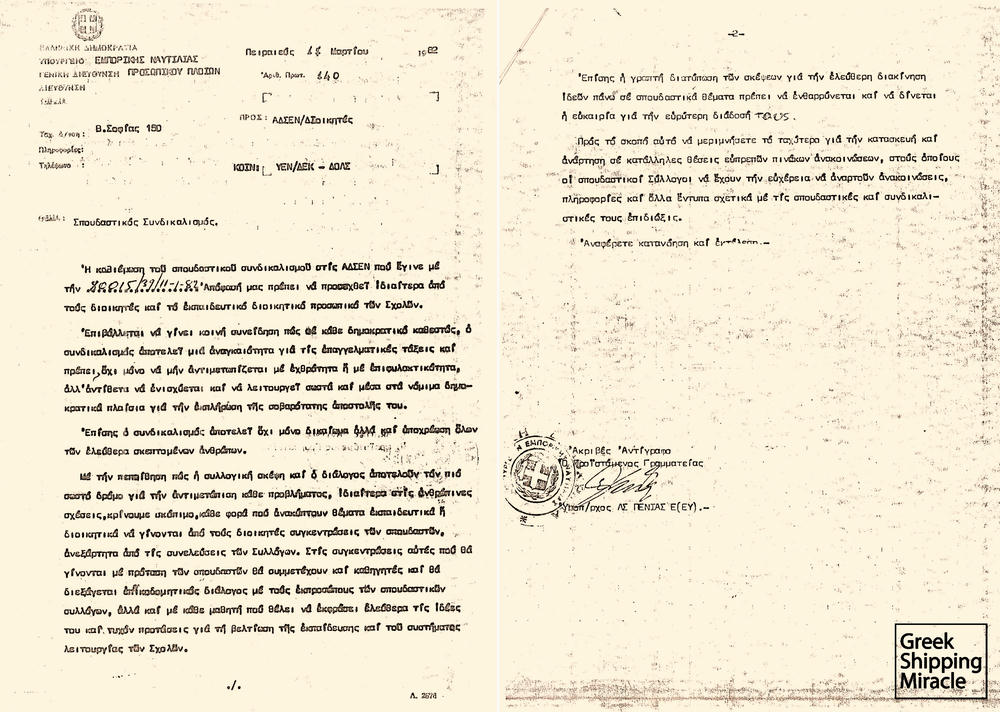

The Papandreou administration faced the challenging task of protecting the Greek registry during this difficult phase. The Prime Minister was well aware of most issues concerning the industry; however, the first signs of the shipping agenda caused concern. Instead of dealing with pressing issues such as the competitive status of the Greek-flag ship, the Minister of Merchant Marine urged students of the maritime school in Aspropyrgos, Athens to shed their uniforms and establish Unions in order to fight for their rights “with stubbornness and consistency”.

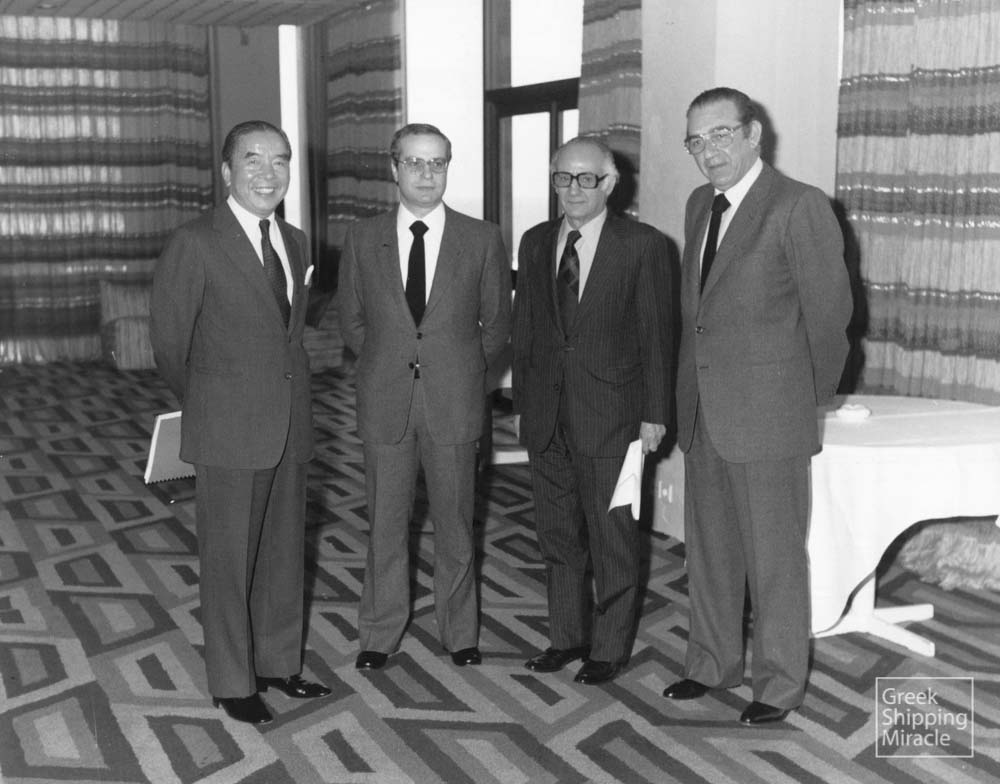

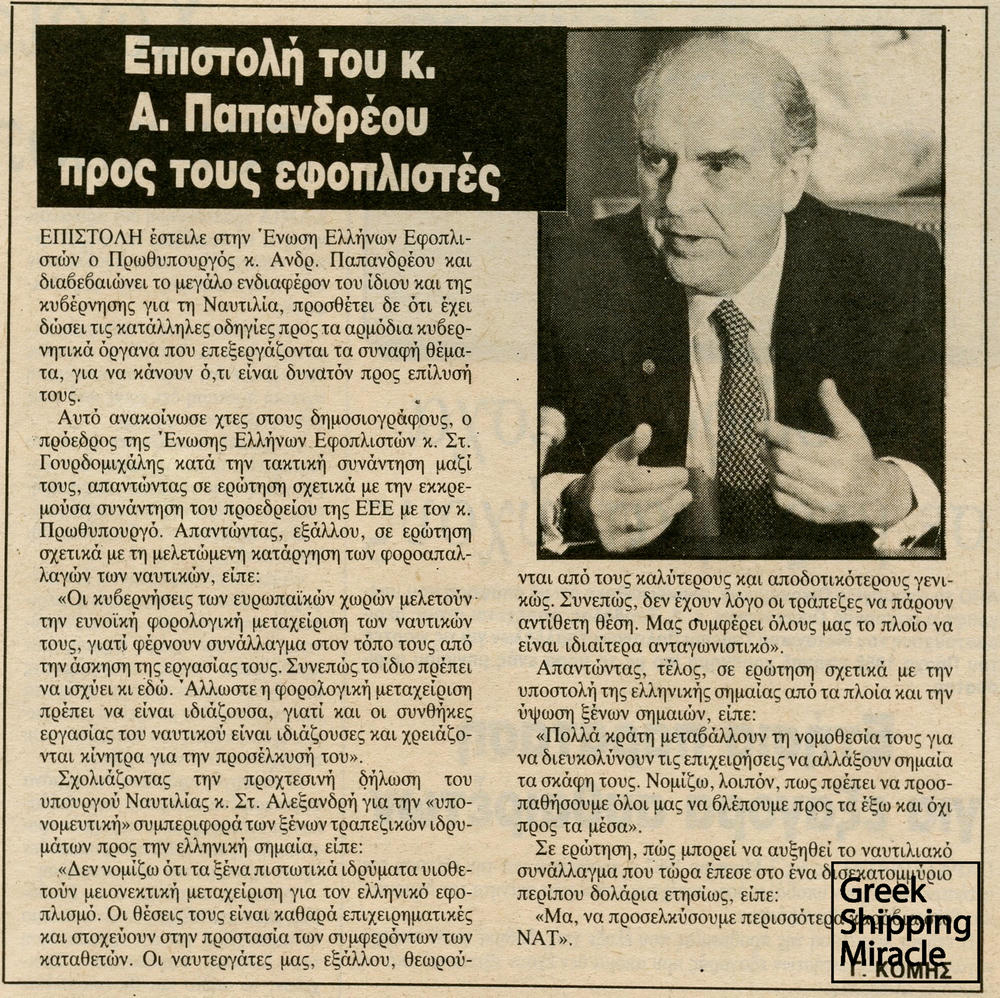

The Prime Minister held an official meeting with shipowners, during which he outlined government measures to combat the consequences of the crisis; however, time went on without any action being taken.

On 4 June 1982, a joint commitment by the Union of Greek Shipowners and the Panhellenic Seamen’s Federation, led to the realisation of a unique project. The establishment of the Hellenic Marine Environment Protection Association, known as HELMEPA, based on an idea by George P. Livanos -who was also the driving force during the first period of the association’s operation- demonstrated the sensitivity of people engaged in Greek shipping towards the sea long before the introduction of any measures aiming at the protection of the marine environment at an international level.

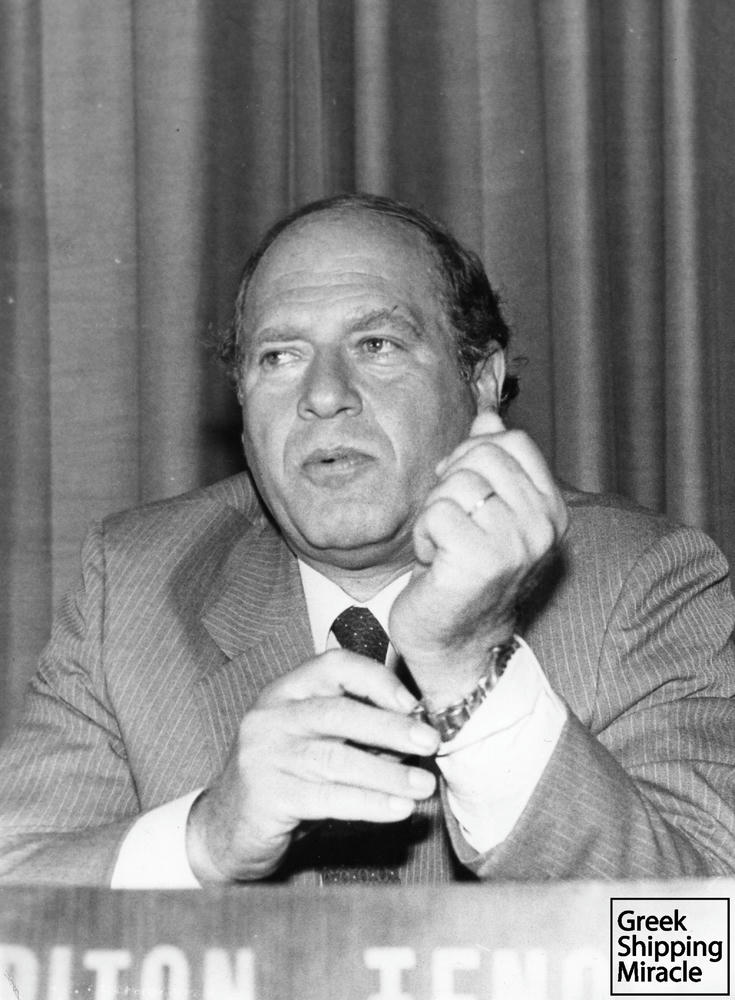

A few weeks later, George Katsifaras took over as Minister of Merchant Marine. One of his first priorities was to resume discussions with owners in order to address issues related to the future of the ailing Greek registry. However, the adoption of any measures was delayed and the only substantial change during this period was the appointment of a civilian as director of the Seamen’s Pension Fund (NAT), instead of a Coast Guard senior officer as was the norm. Over the next few years, NAT became one of the largest burdens on the Greek state budget following the government decision to provide pensions even to individuals who had never served on board a ship and had no relation whatsoever with the shipping industry.

In early 1983, the government finally announced measures to address the problems that had led 700 Greek ships to lay-up berths. However, whilst the relevant bill was submitted to a vote, differences emerged with the initial agreement. The measure of compulsory recycling of marine labour led to an unprecedented confrontation between the government and shipowners, which was even transferred to Parliament. Government and opposition crossed fires; however, this did not stop the bill from passing. As a result, one after the other Greek-flag ships started leaving the registry.

The freight market continued declining at a fast pace over the next couple of years. This led several financiers to the adoption of questionable methods of managing the problems faced by the industry. Such attitudes were mainly demonstrated by US banking institutions, lacking experience in shipping finance at the time and consequently never having faced a crisis of this magnitude. The lack of realism by many senior bank officers while addressing unprecedented problems caused great losses to both banks and shipowners, leading many maritime enterprises to bankruptcy. However, there were financiers that showed understanding and tolerance, appreciating that the market would recover, sooner or later. Many owners succeeded in close collaboration with their financiers to substitute old tonnage with newer vessels whose values were highly depreciated due to the crisis. Using the same method, more and more entrepreneurs strengthened their fleets with quality ships. Nearly all these vessels were placed under foreign flags, enabling them to operate competitively despite the crisis. When the freight market eventually regained its normal levels, losses were recovered through the sale of ships at substantially higher prices.

The process of acquiring new tonnage during those critical years could be compared with initiatives taken in the immediate post-war period, when almost the entire Greek-owned merchant fleet was re-established by ships under foreign flags. This time, however, it was not only Greek owners but also other nationalities that gave preference to flags of convenience, while several European owners requested their governments to establish open registries. Everyone involved in world seaborne trade appreciated that survival and progress depended on being competitive. This led over the years to the weakening of national fleets and the reduced role of the International Transport Federation.

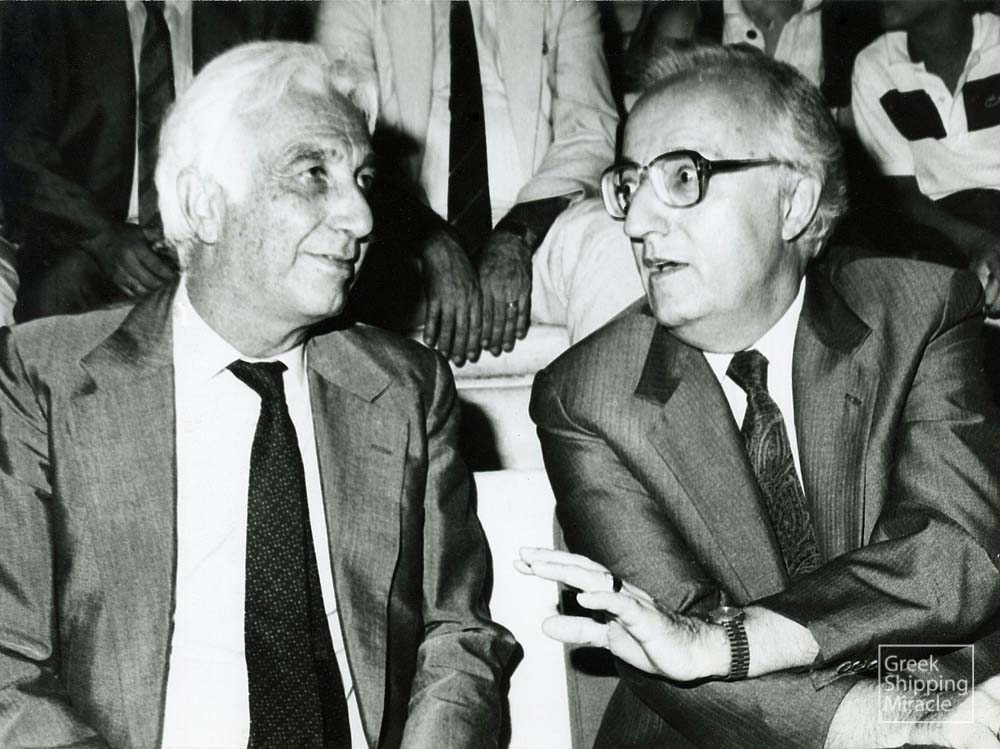

On the occasion of the election of a new president of the UGS board at the end of 1984, shipowners requested an official meeting with the Prime Minister. Andreas Papandreou, who had last officially met with industry representatives in January 1983, did not respond, maintaining this stance until he left power in 1989.

Consequently, the Greek shipping industry continued its course without any meaningful dialogue with the government, until the second victory of the governing party, in the June 1985 elections. Gerasimos Arsenis, Minister of Finance, was also sworn in as Minister of Merchant Marine. This surprising development, however, was a sign that the government was planning to abolish the Ministry of Merchant Marine.

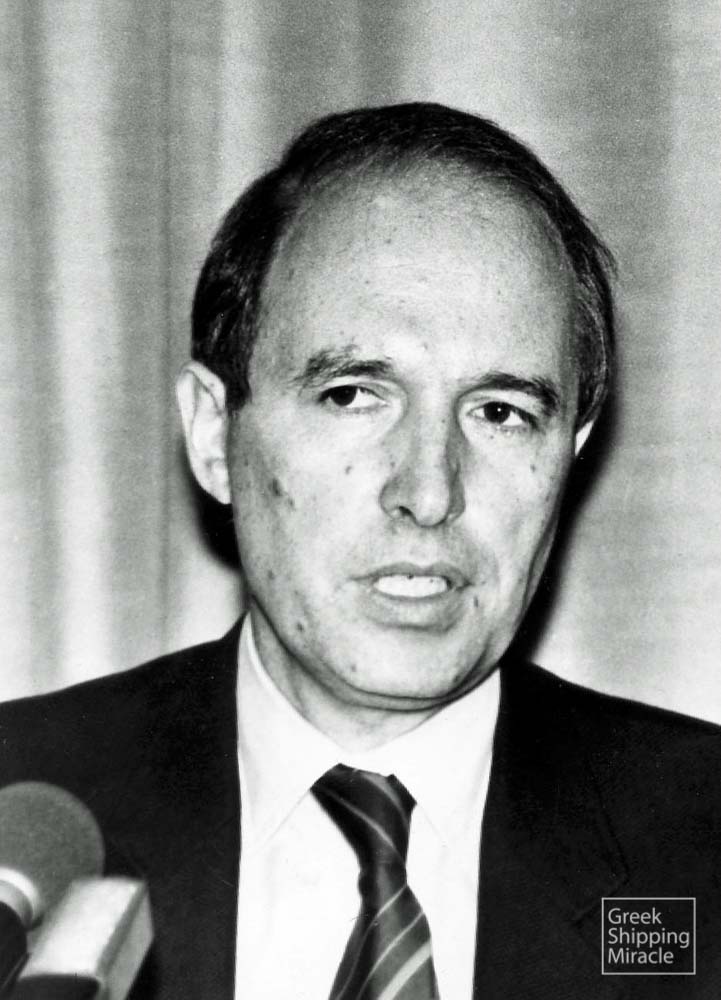

The reaction of the maritime community was immediate, forcing the government to revise its decision to abolish the Ministry. A new Minister of Merchant Marine was sworn in, while at the same time a Piraeus-elected MP, Costas Simitis, was appointed Minister of Finance. A short while later, the law for crew employment recycling was abolished by the Merchant Marine Minister, who labeled it a law for the recycling of unemployment.

The dramatic decline of the number of Greek-flag ships and the parallel increase in Greek-owned foreign-flag vessels finally activated the government. At the end of the summer of 1986, the freight market began to show signs of recovery. Taking advantage of improved sentiment, the Minister of Merchant Marine launched a campaign, personally visiting shipping offices, aiming in the creation of favourable conditions for the registration of ships under the Greek flag.

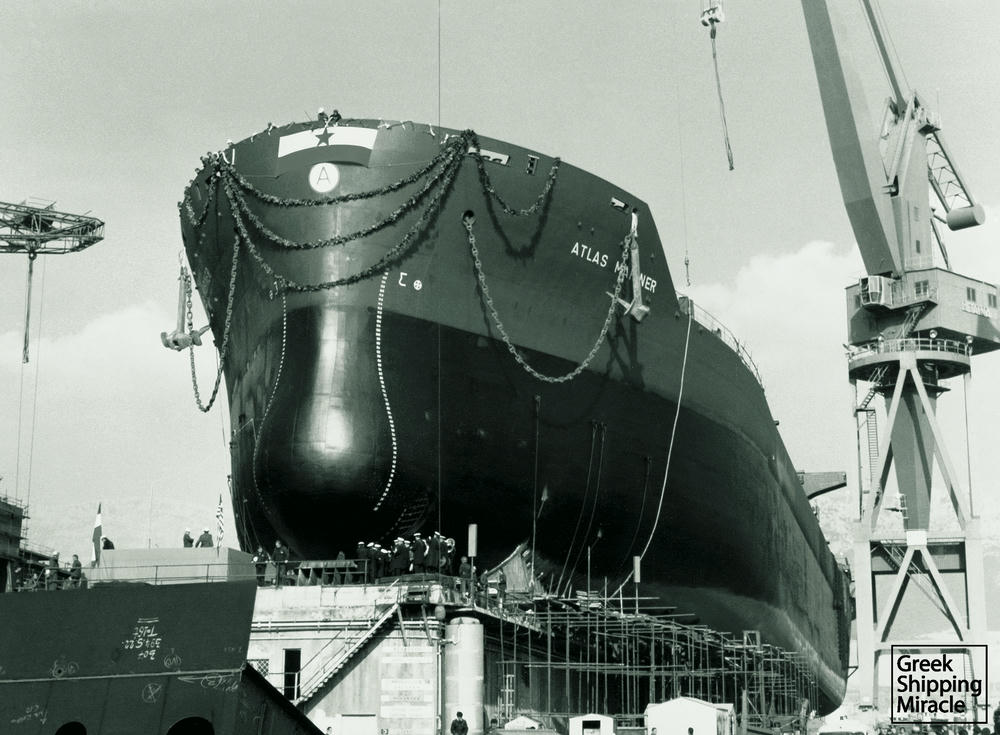

In late 1986, the Prime Minister accepted an invitation from shipowner John Latsis to attend a ceremony on the occasion of raising the Greek flag on board the giant tanker HELLAS FOS. A few months later he laid the cornerstone of the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Centre, one of the largest charity projects in Greece by members of the shipping community.

However, it was too late for the revival of the register. The shift to foreign flags offering competitive operation to ships was firmly established, not only among Greeks but also to most other nations. It was only natural for them to endeavour maximising returns after years of deep recession.

The constant change in Merchant Marine Ministers, as well as the shipping policy adopted in the following years, made things even worse. The Greek registry remained merely an observer of the explosive development of Greek-owned shipping, once again the global leader in the industry, with a renewed fleet.

In June 1989 a coalition government headed by Tzannis Tzanetakis was sworn in, following a landmark decision by the conservative party New Democracy, the Greek Communist Party (KKE) and the Coalition of the Left. One of the administration’s first decisions was the adoption of sandwich courses at maritime schools in order to upgrade the education system at a time that a census was revealing a dramatic reduction in the number of Greek seafarers.

Another dramatic reduction, which was proven irreversible, concerned 1,900 Greek-flag ships that were lost from the national registry in just a decade. It was the biggest loss Greek shipping had suffered during peacetime.