Shipping in Wartime (1912-1918)

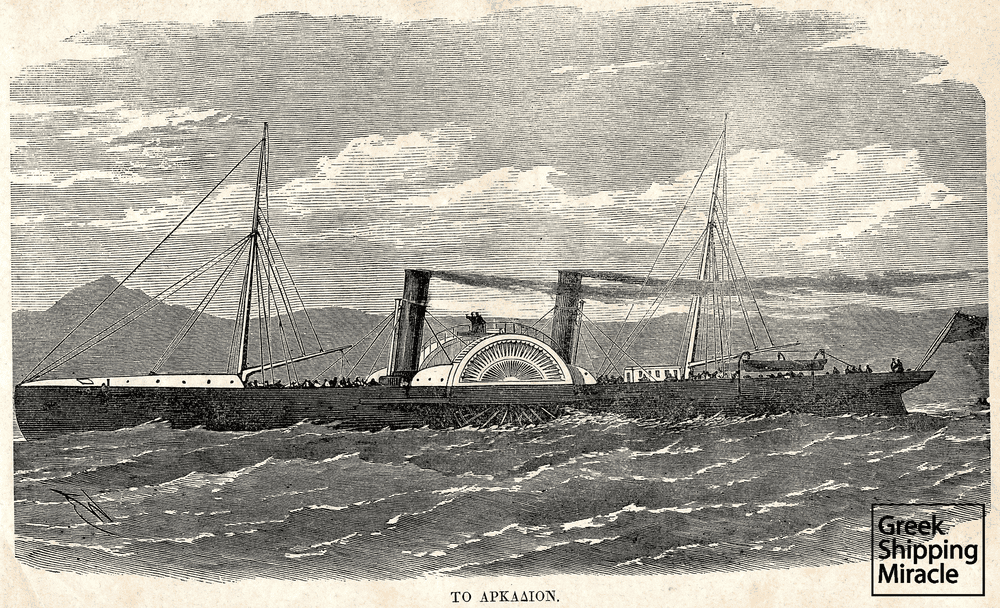

Since the mid-19th century, Greek steam shipping had contributed to the attempts to free Crete from Ottoman rule from 1866 to 1896 and during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. Regrettably, the unfortunate outcome of the latter did not allow the Greek Maritime’s contribution to stand out. On the other hand, the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 were set to establish a completely different picture.

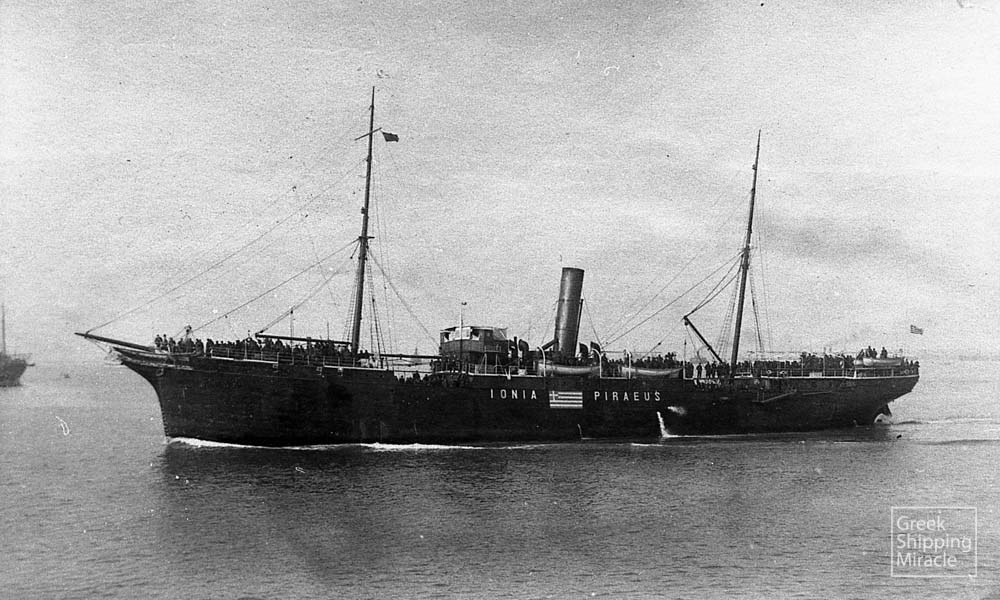

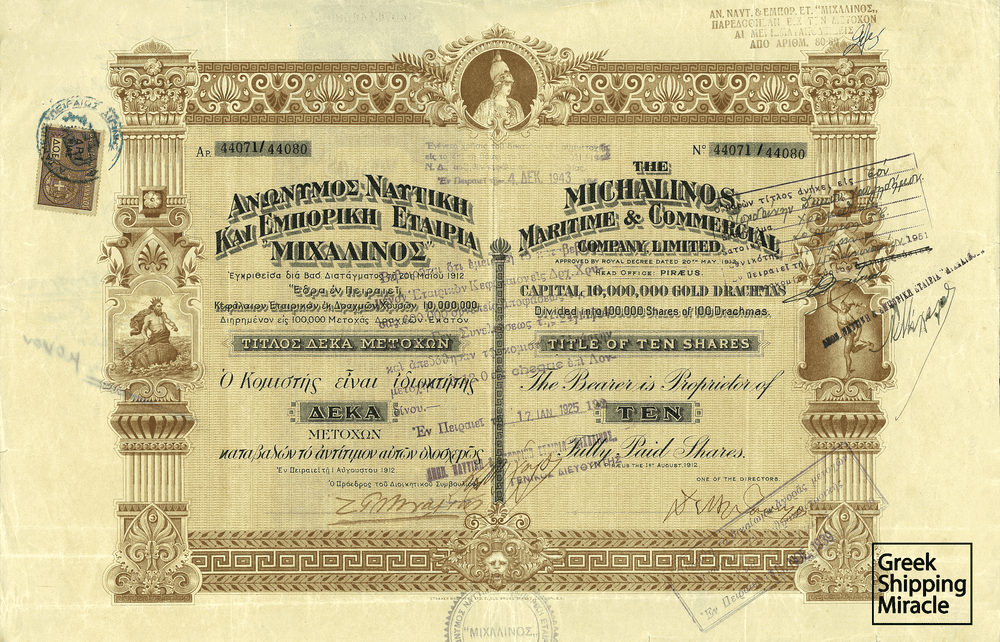

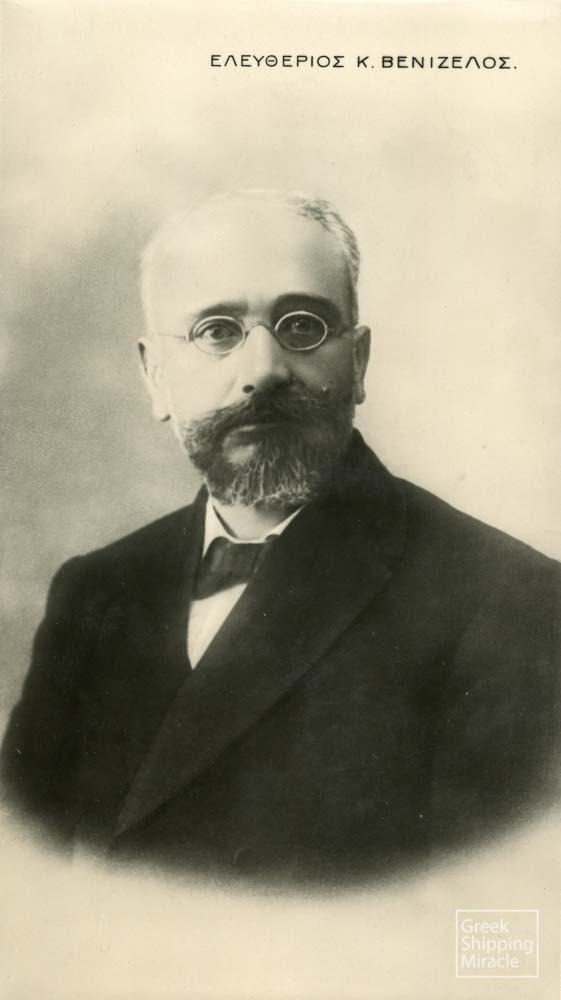

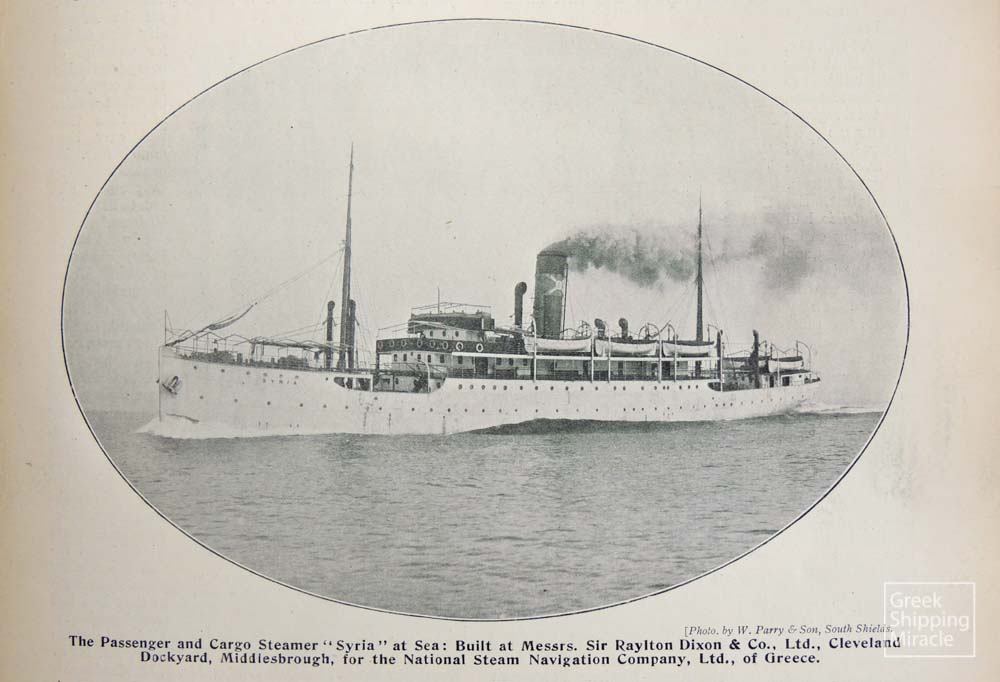

From the very beginning of 1912, Eleftherios Venizelos, the Greek Prime Minister, was working hard in realising his vision of re-establishing the status of Greece as a great country. At the same time, the Greek-flagged steamship fleet had expanded to 350 vessels. The prevailing circumstances encouraged the fleet’s further expansion and, as a result, by September 1912, when the declaration of a war was imminent, 40 more steamers were sailing under Greek colours.

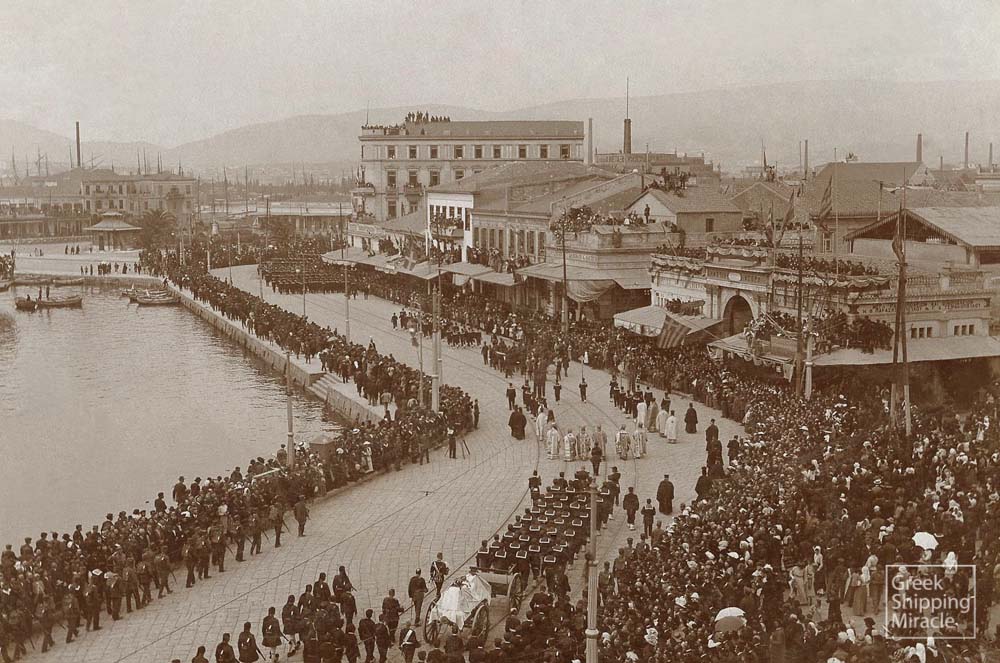

On 20 September 1912, several days before the outbreak of the imminent Balkan Wars, the Greek government requisitioned all merchant ships at the port of Piraeus. Additional ships were requisitioned in other ports of Greece, whilst Greek steamers in foreign ports were given orders to sail full speed to Greece.

However, the whole process was overshadowed by an unfortunate incident. No one in charge thought to notify Greek steamers in ports under the control of the Turks. The latter, taking advantage of this oversight and in breach of international law, withheld all Greek steamships a few days before the declaration of the war. As a result, several Greek vessels did not participate in the war and even worse, were placed at the service of enemy forces. Ultimately, 40 of these ships sailed to Constantinople, where they remained inactive until the end of the war.

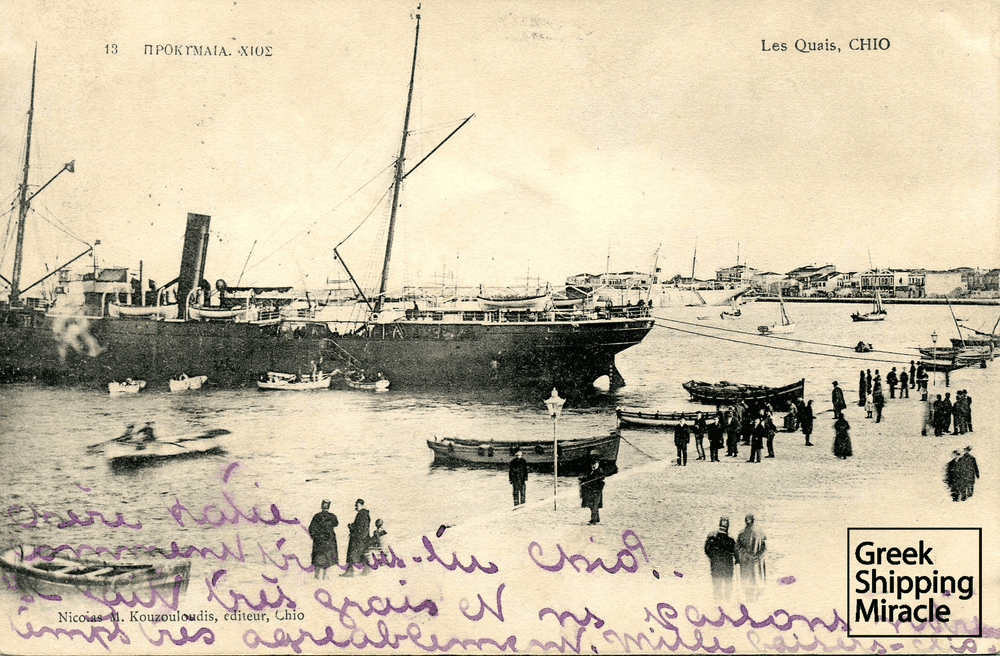

The victory in the Balkan Wars resulted in the recovery of Greek territories which were under Ottoman occupation for centuries. Amongst these were the island of Chios and the adjacent islands of Oinousses. Both were destined to play a key role in the course of Greek shipping during the course of the 20th century. Many seafarers from these islands, who had already demonstrated outstanding performance since the middle of the 19th century, went on to become world-class shipowners over the next decades.

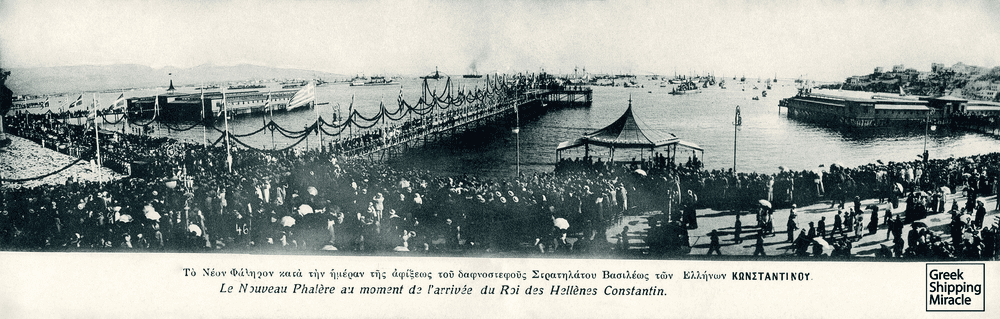

The major contribution of the merchant fleet to the successful outcome of the Balkan Wars provided shipping with two prominent supporters, Eleftherios Venizelos and admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis, an officer whose leadership was instrumental to the war’s successful. Both had witnessed and appreciated the invaluable role of shipping, especially in terms of the rapid transportation of troops and supplies.

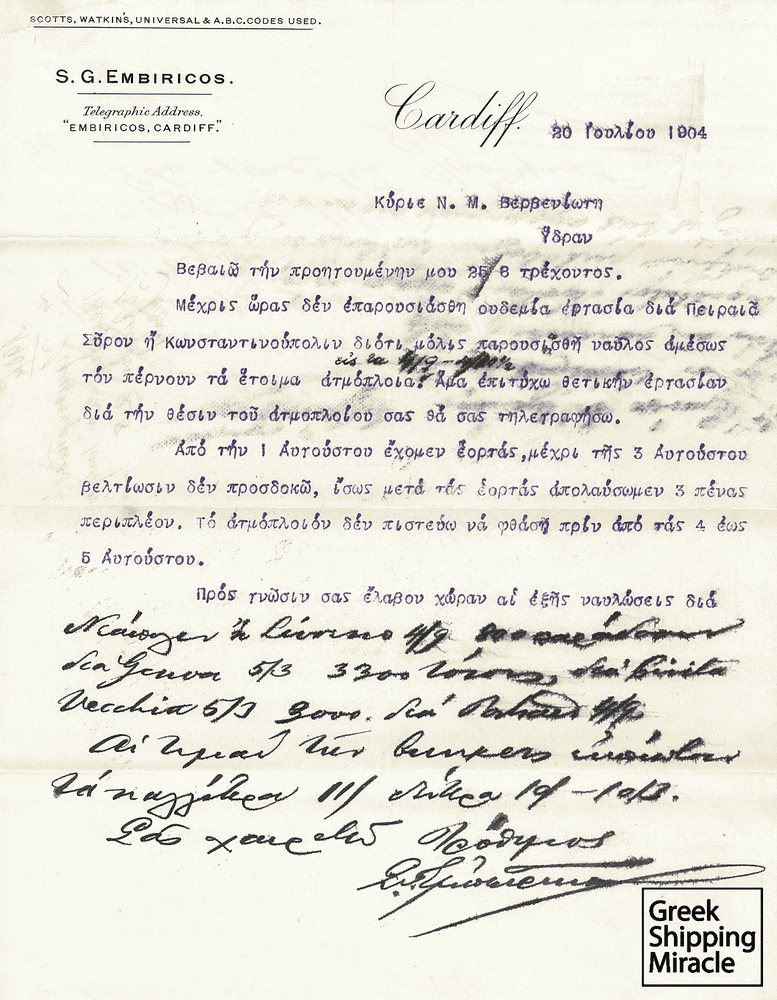

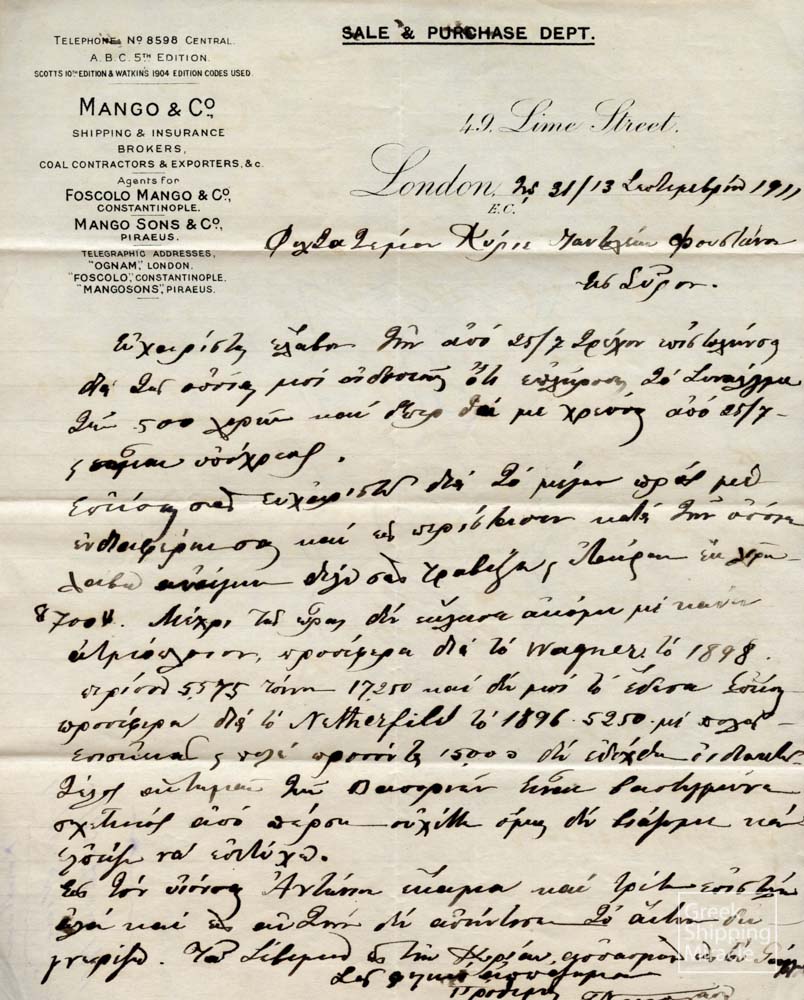

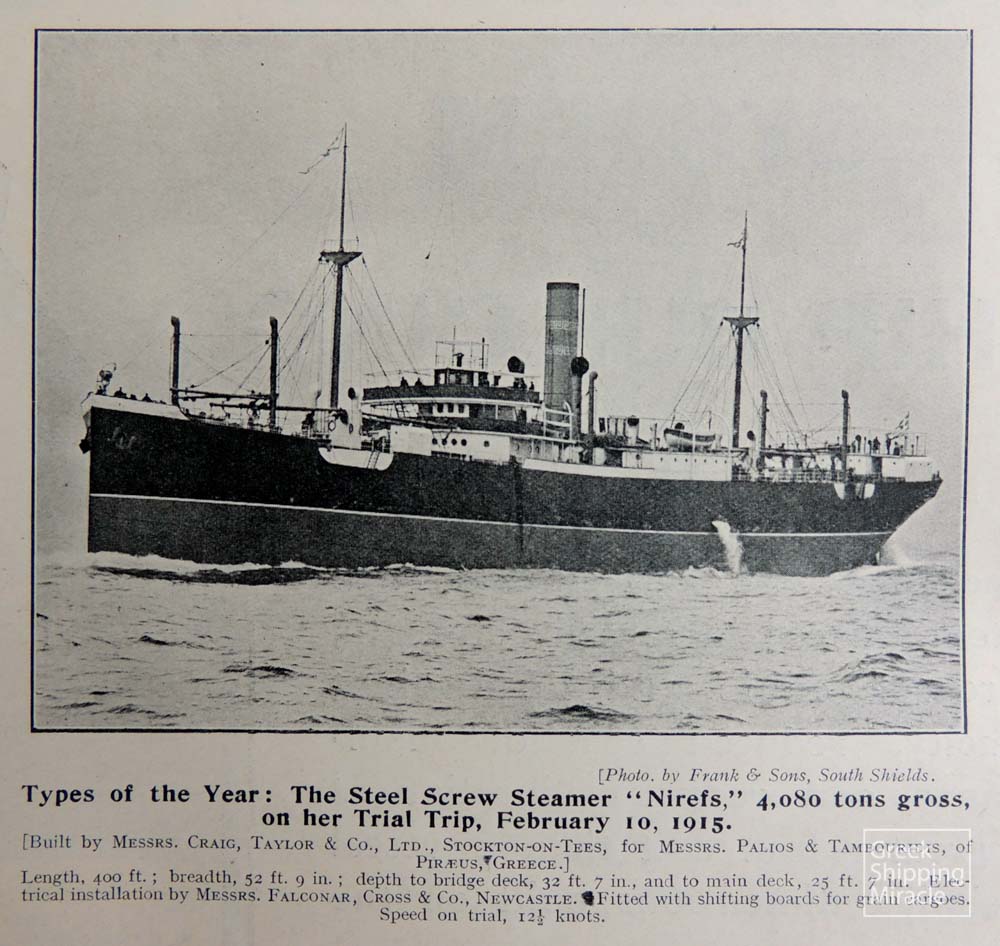

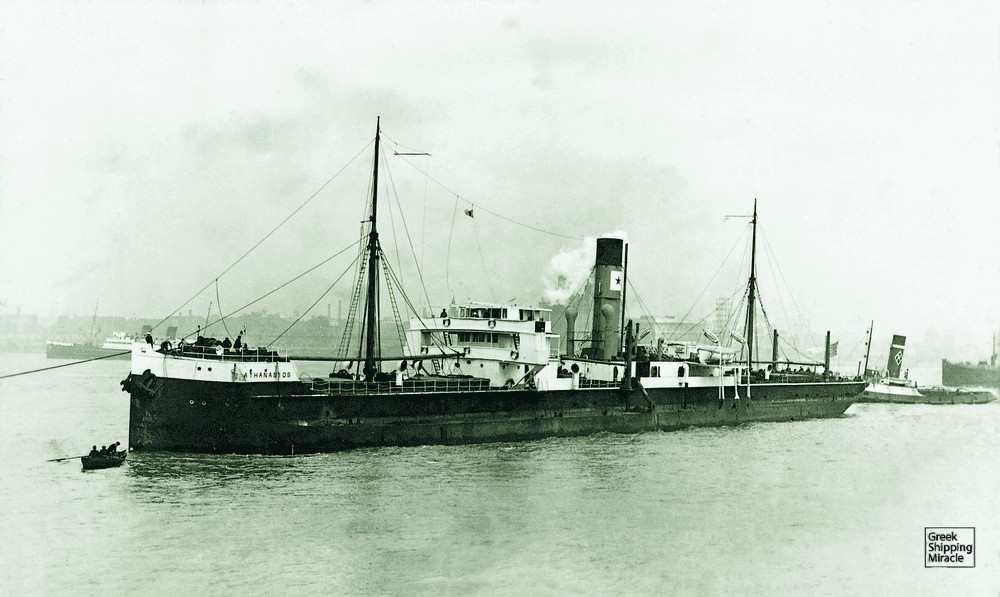

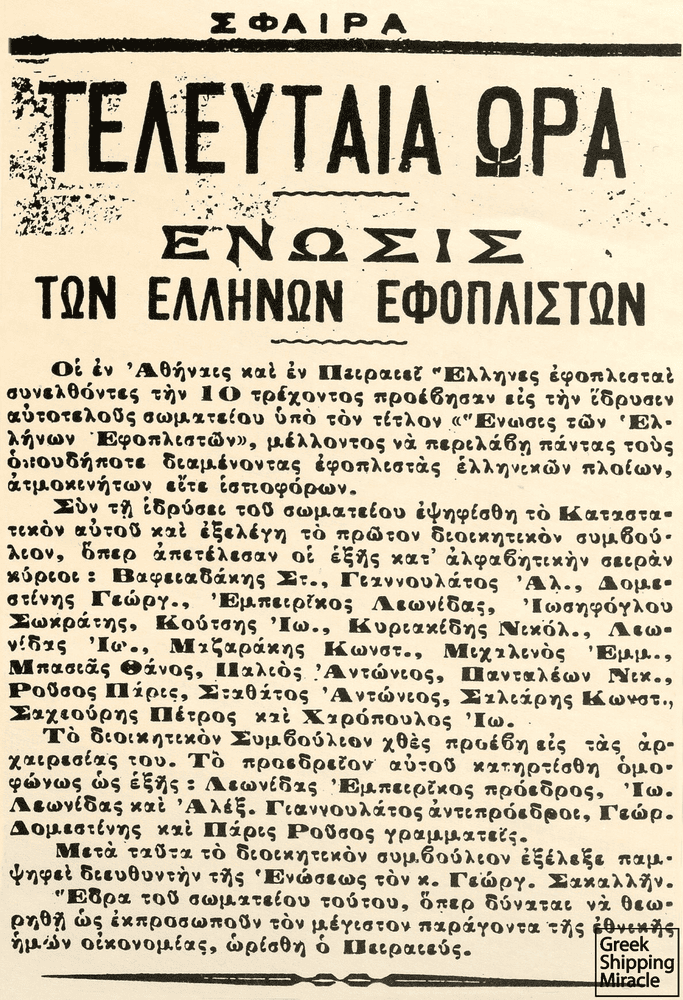

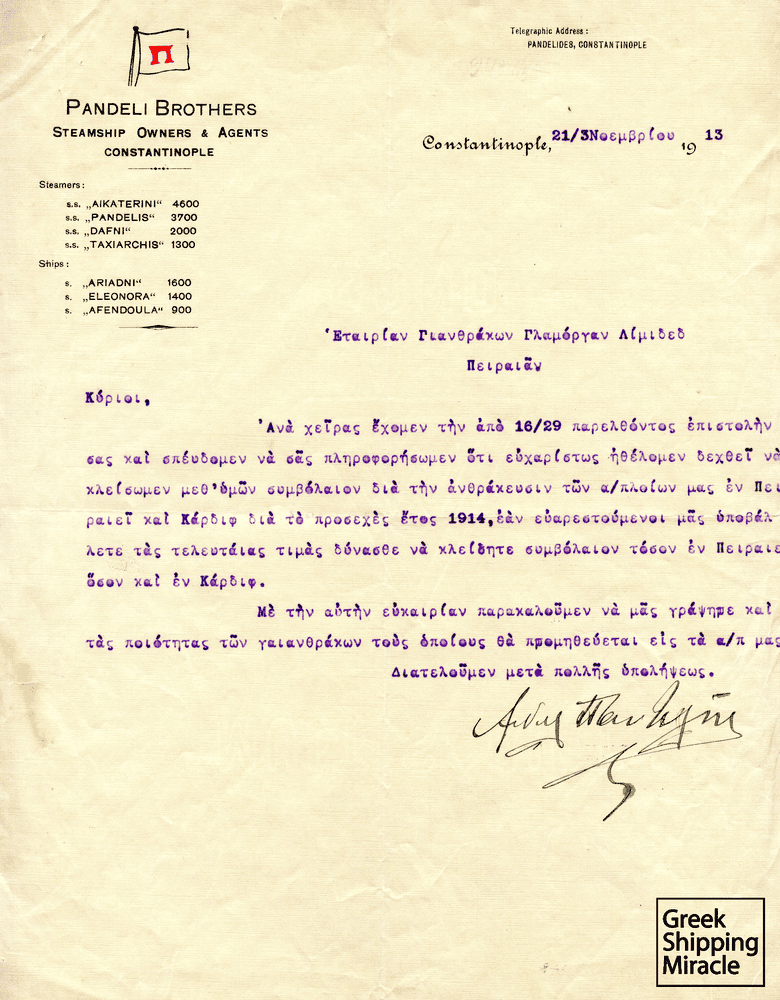

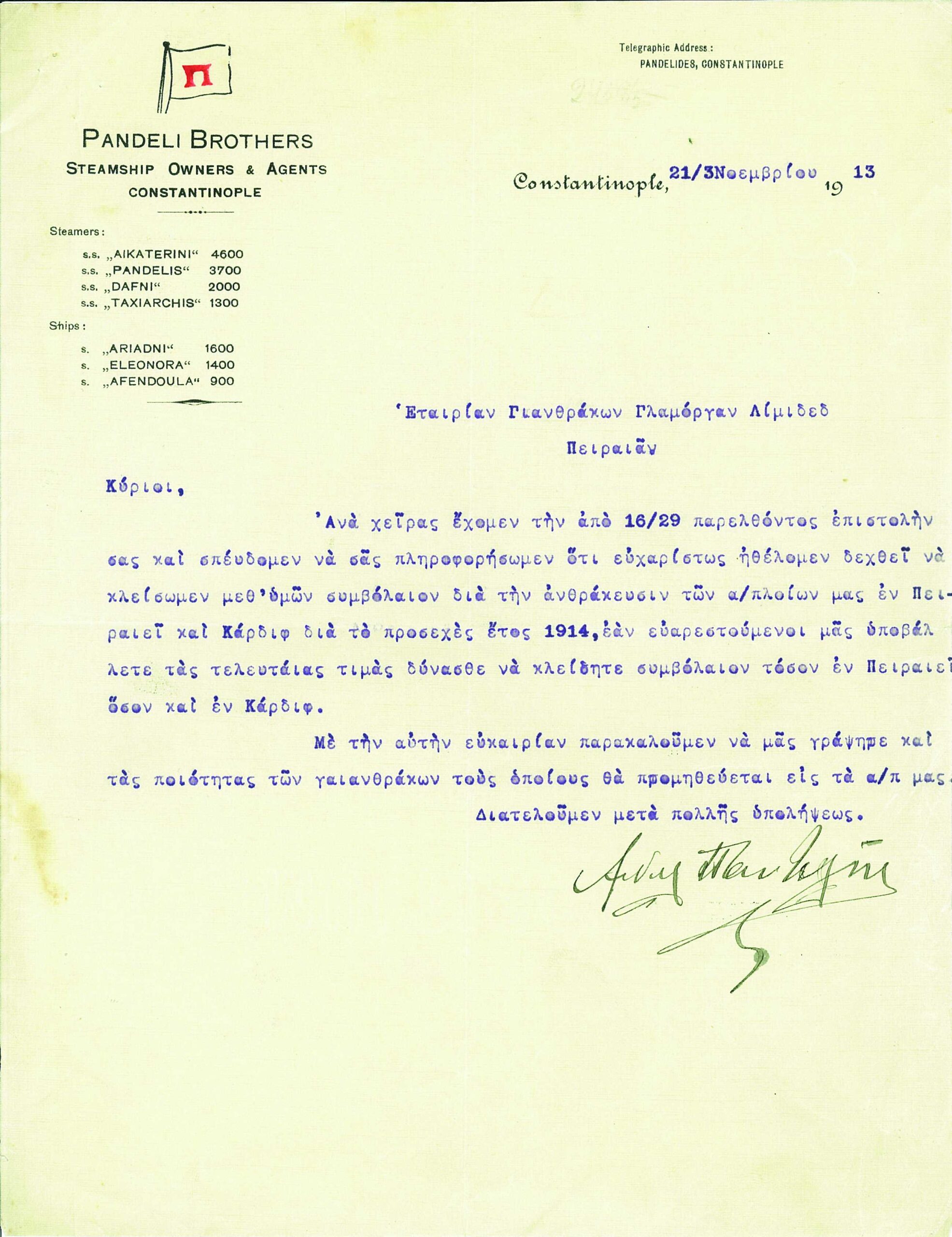

At the same time, the experience gained through various events during the Balkan Wars gave rise to strong concerns on the part of the shipowners. Several of them, led by Ghikas Coulouras, a master mariner from the island of Hydra, supported the need for the establishment of an association to safeguard the interests of the industry. However, this was not a simple issue at the time as on the one hand most shipowners were masters of their own vessels and, on the other, the majority of the few Greek shipping offices were based in the United Kingdom and specifically in London, Cardiff and Newcastle. As a result, nothing changed until the outbreak of the First World War, in September 1914, apart from the fact that approximately 100 steamers had been added to the Greek fleet.

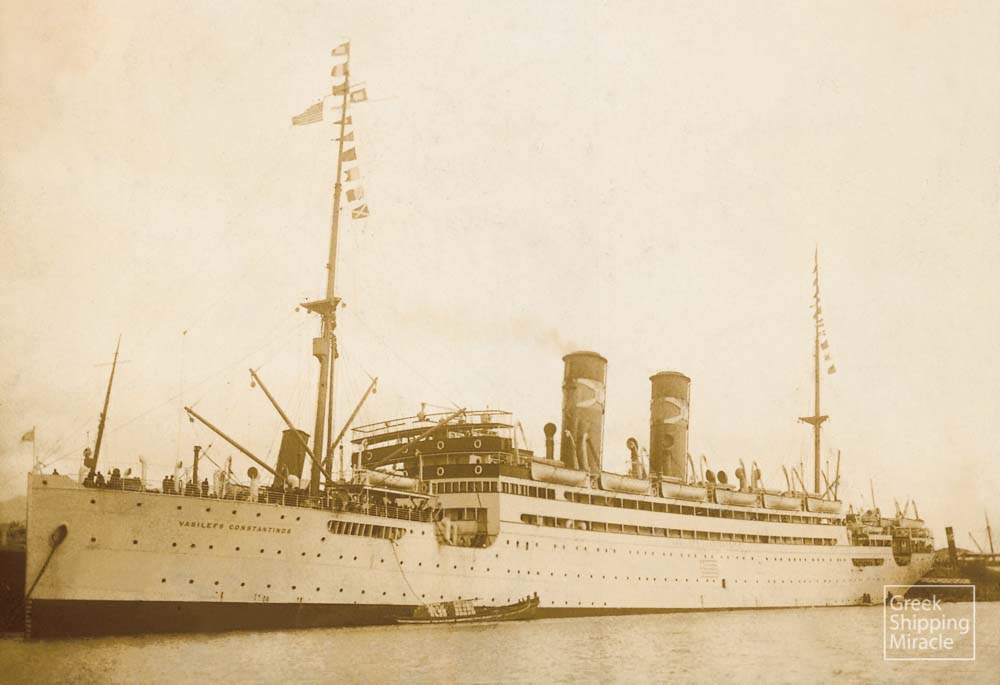

A disagreement between King Constantine and Prime Minister Venizelos resulted in Greece remaining neutral. By March 1915, the Greek fleet of 500 steamships was ranked 11th in the world, with excellent prospects of further development.

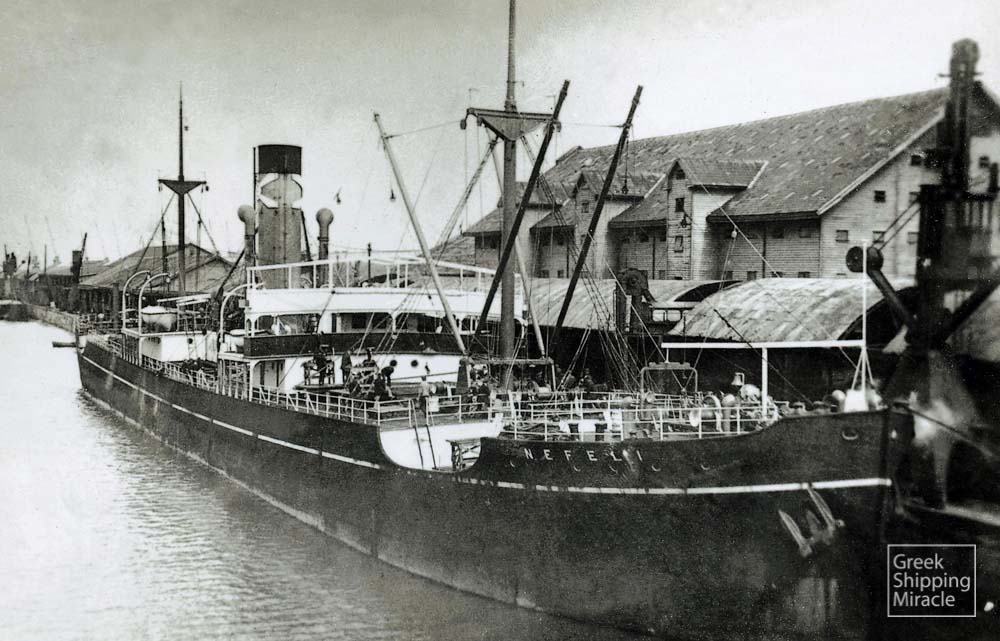

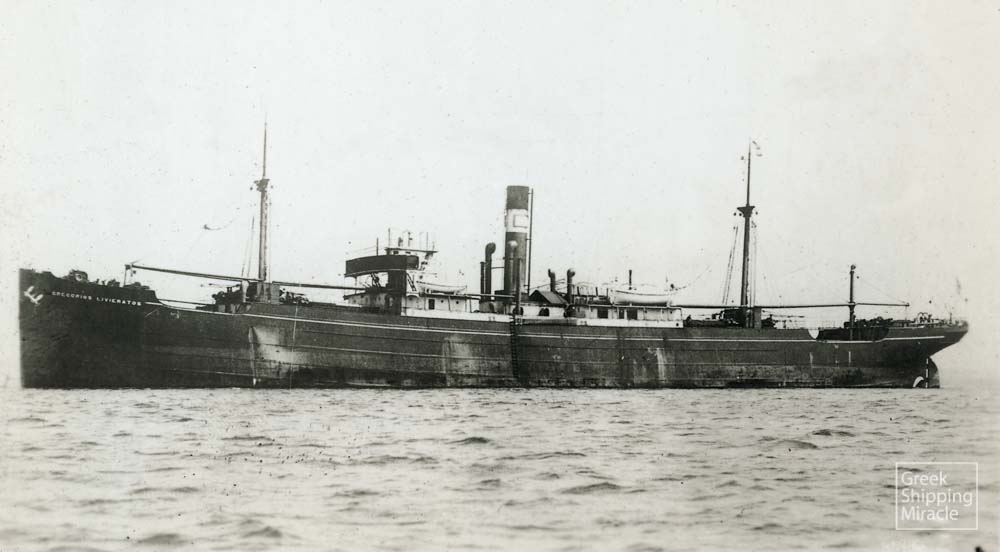

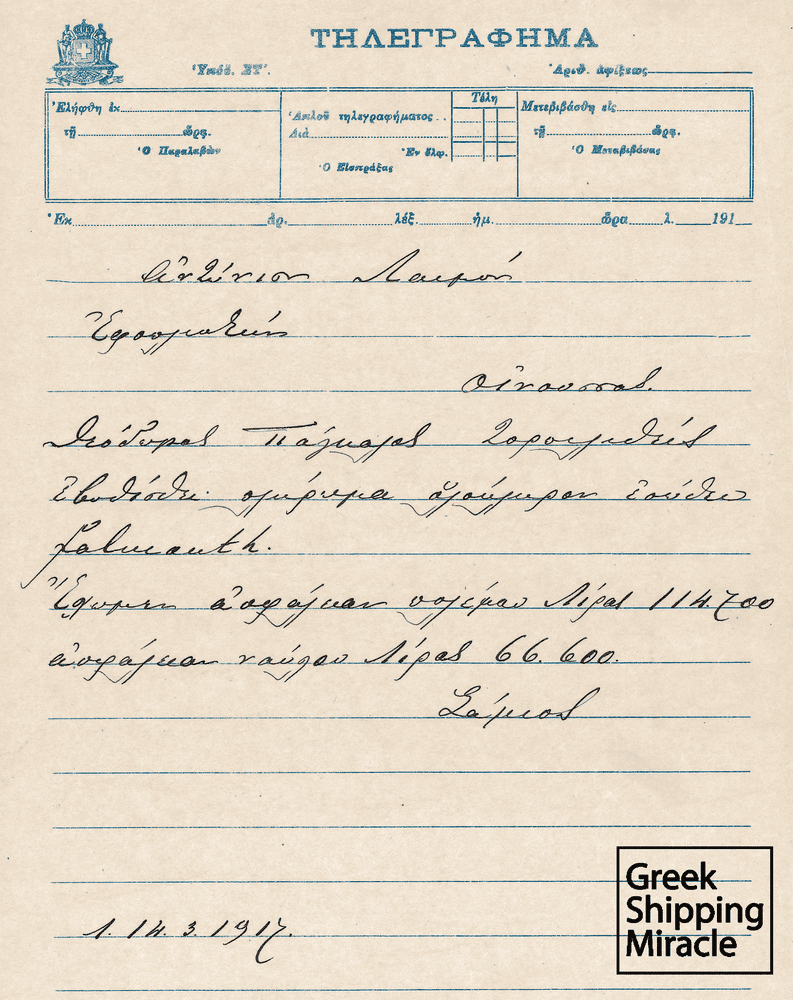

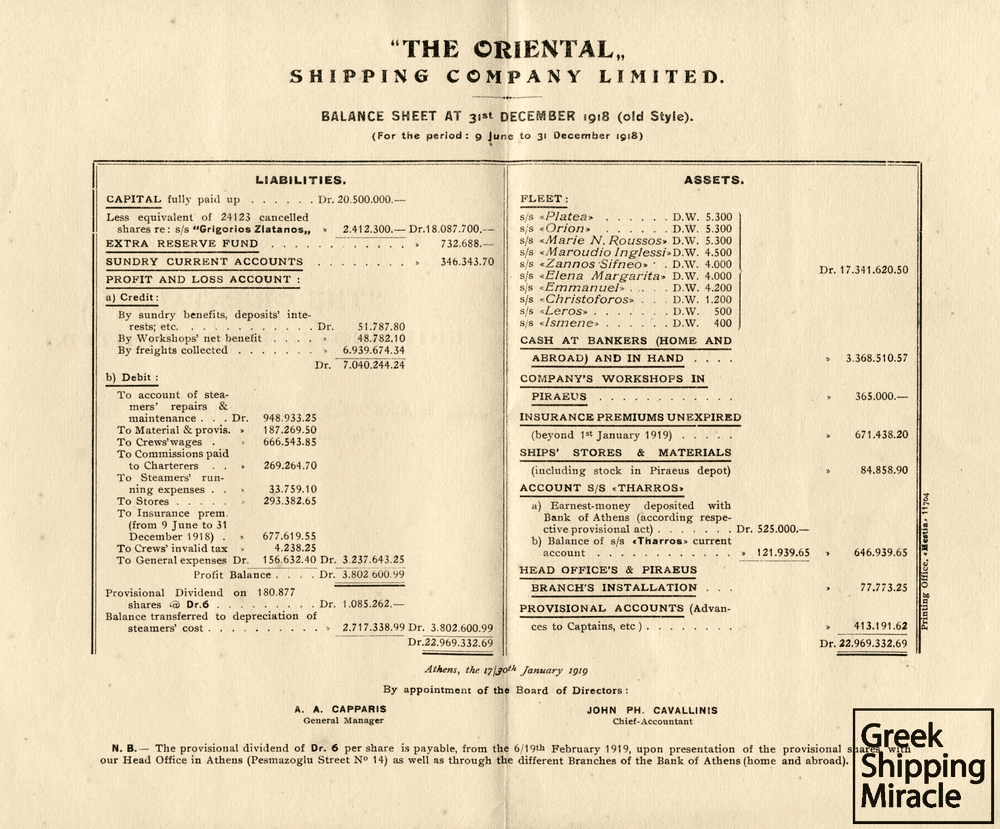

However, at this point the scene began to change dramatically. On the one hand, the state, troubled by political instability, failed to show any substantial interest to the shipping industry and, on the other hand, the absence of a collective body that could successfully address unprecedented situations created by the War on a daily basis led to adverse results. Many shipowners, influenced by the continuous rise in the value of ships, began selling their steamers. Their decision was further strengthened by the threat of German submarines, which had begun to hit even neutral Greek vessels. Within a few months, before the government realised the enormous damage done and had the sale of steamships prohibited, the Greek register had lost more than 100 ships.

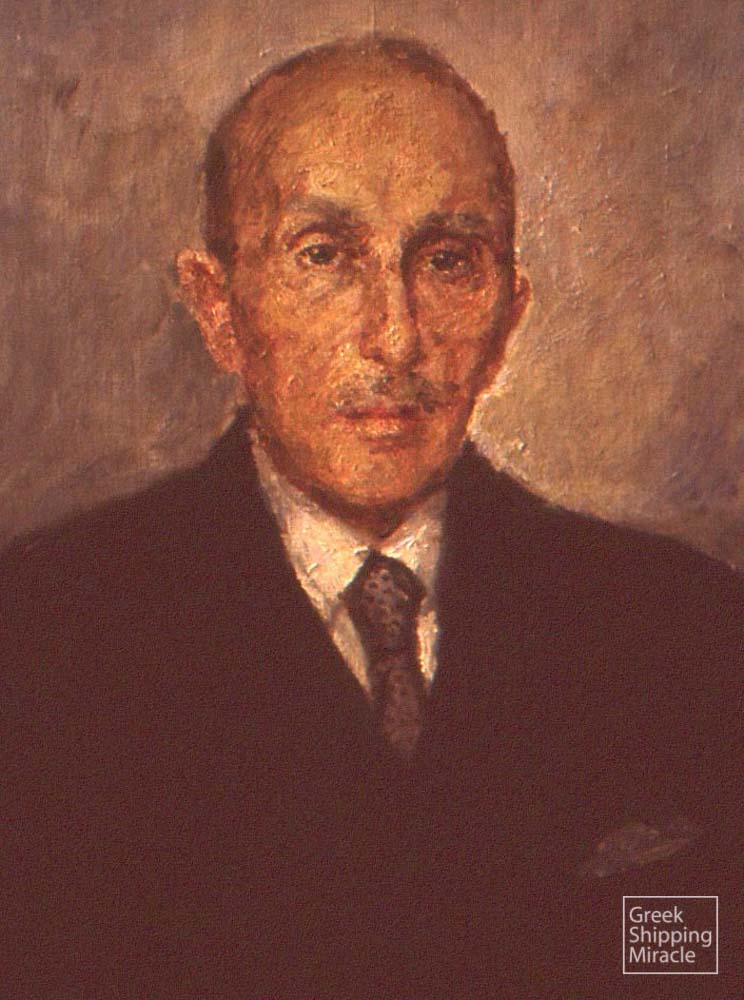

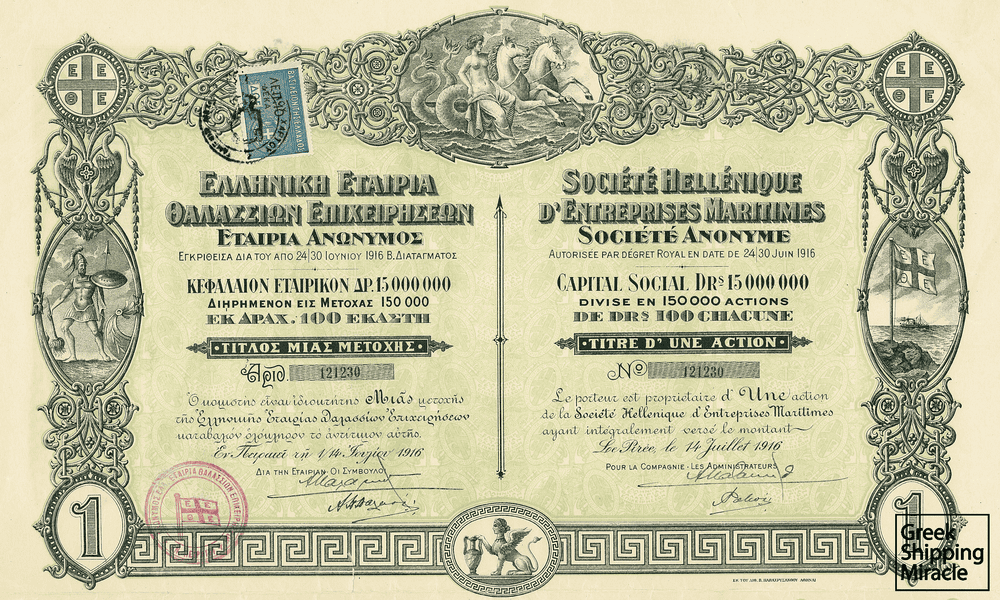

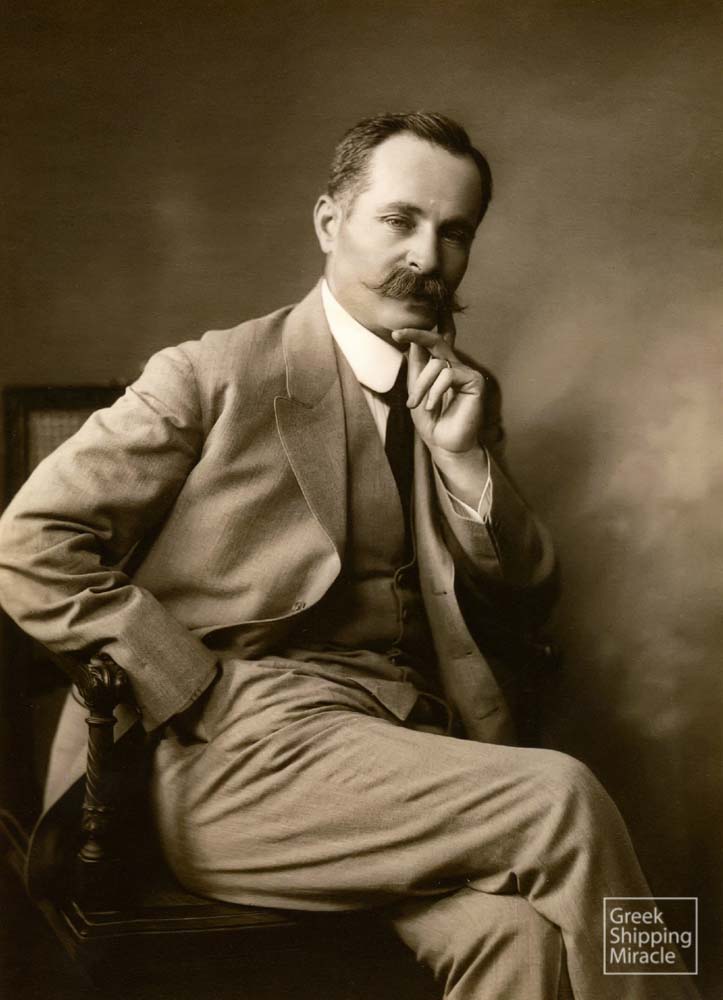

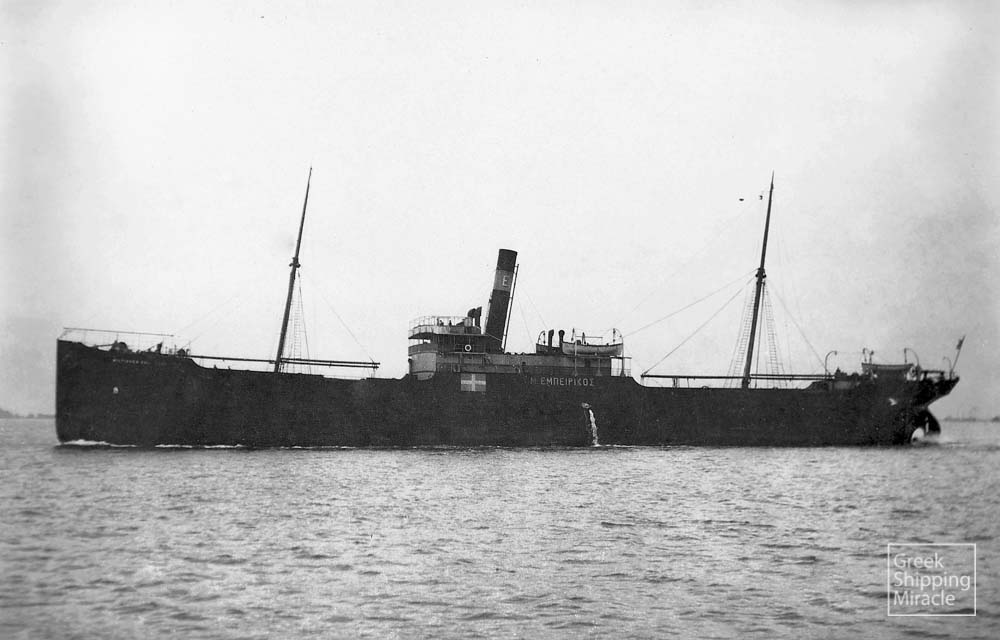

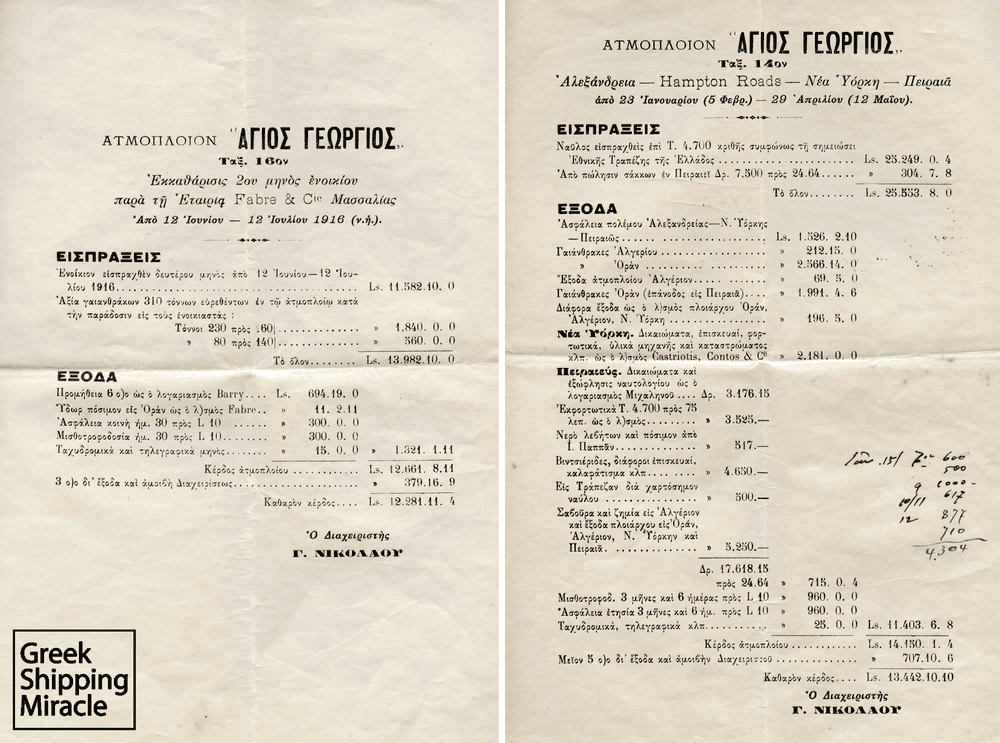

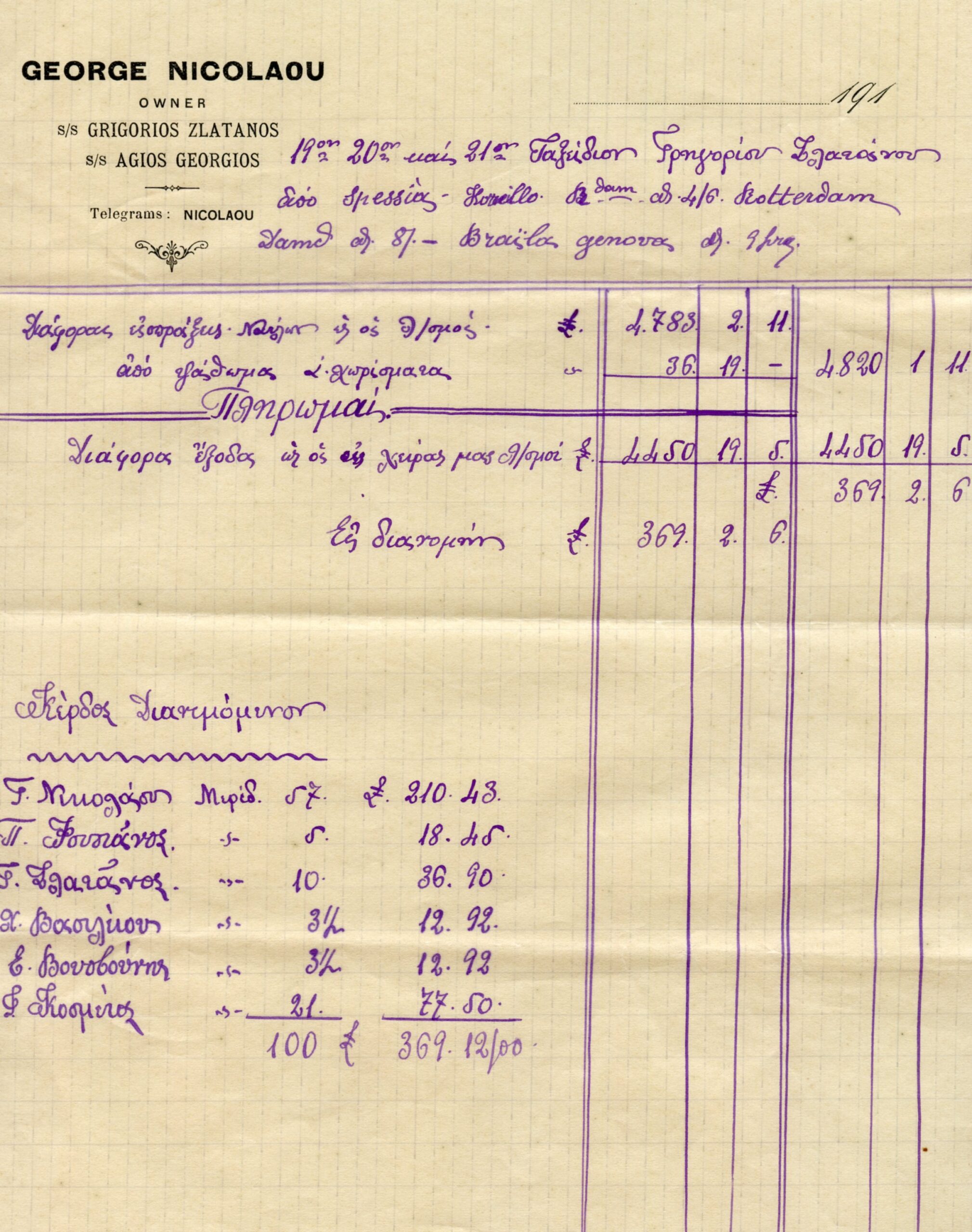

Meanwhile, the astronomical increase in the hires of steamers due to the War brought huge profits to shipowners. At the same time, the significant rise in transport costs greatly increased the price of imported goods and caused distress between Greek shipowners and people in their own country for the first time. This development revived the idea for the creation of an association aiming to address the issues concerning the industry and this led to the establishment of the Union of Greek Shipowners in Piraeus on February 16, 1916, with Leonidas A. Embiricos elected as first president. Most of its founding members belonged to the core of supporters of Venizelos’ party and followed him to Thessaloniki where he formed his new government.

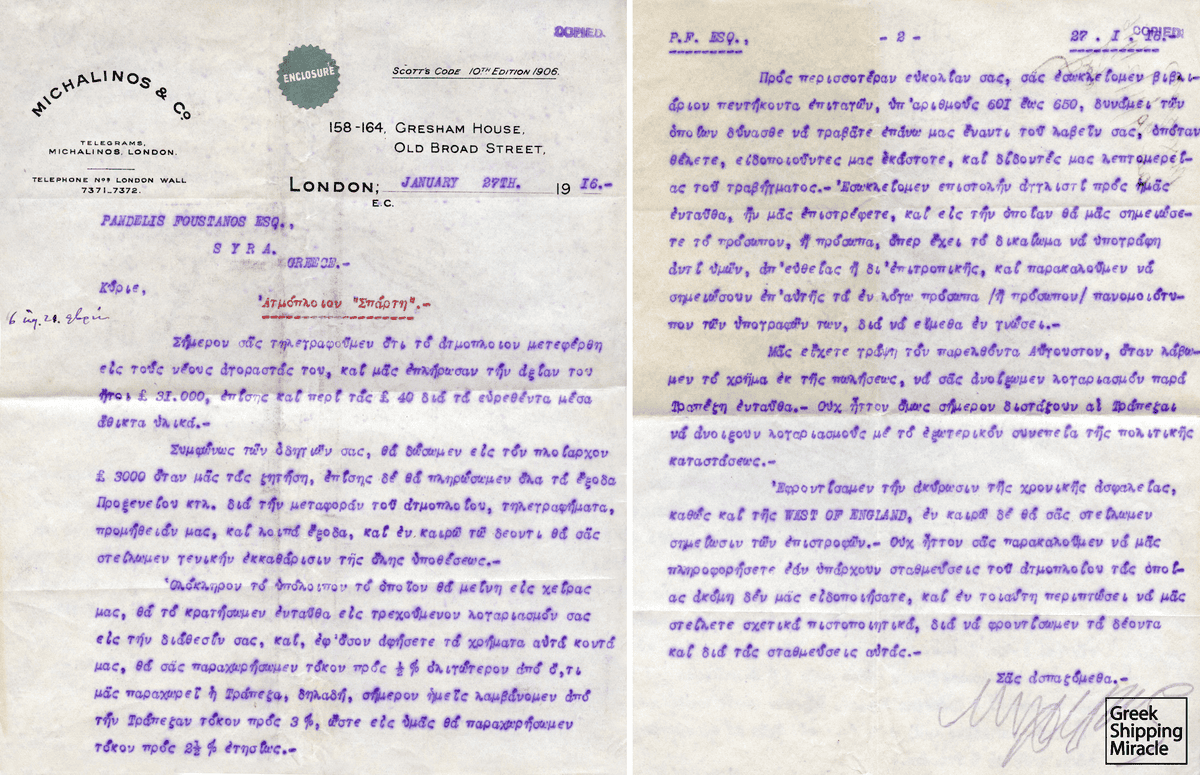

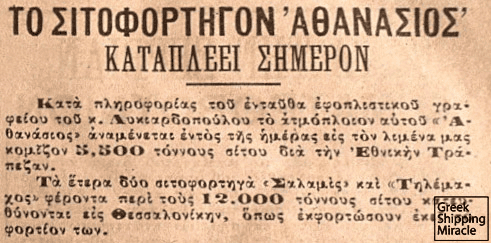

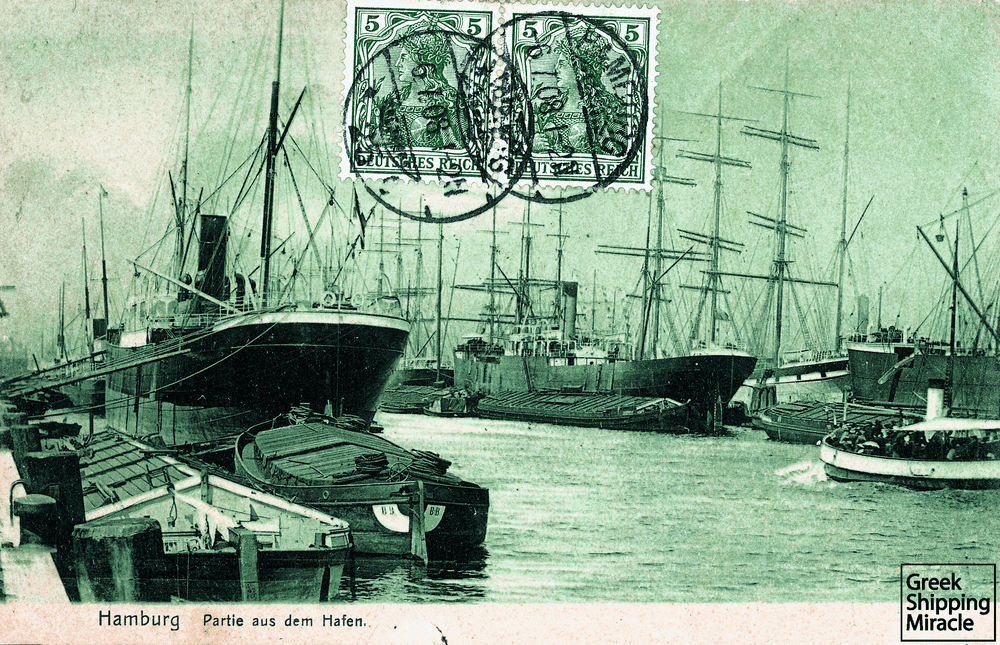

With Greece’s entry to the War in 1917, the centre of the Greek shipping activity moved to the United Kingdom, where a substantial number of Greek offices were already operating. The entire Greek steamship fleet was chartered to the British government at significantly lower rates than those prevailing at the time. Also, restrictions were placed on the amount of insurance that would be paid back to the Greeks in the event of a war loss. The ships provided by the Greeks for the Allied Forces were employed in the most dangerous routes – transporting coal from the United Kingdom to the Mediterranean and minerals from the Mediterranean to the United Kingdom – resulting in the decimation of the Greek fleet within a short space of time, mainly by German submarine fire. By the end of the War, the Greek merchant fleet had comparatively recorded more losses than most other nations and the number of the remaining ships did not have the slightest resemblance to pre-war levels.

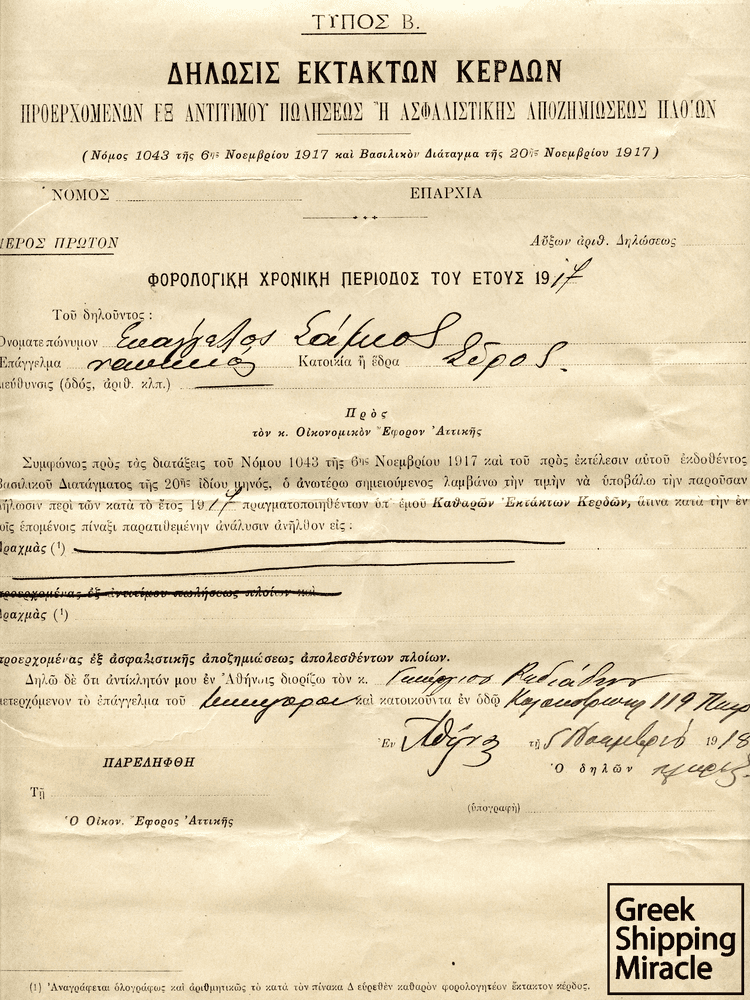

Despite the above, many Greek shipowners made extraordinary profits during the War from sales, insurance claims and the operation of their steamers, especially during the years of neutrality in 1915-1916. This was sufficient to enable them to invest again in steamships, whenever they felt that they should return competitively to the market.

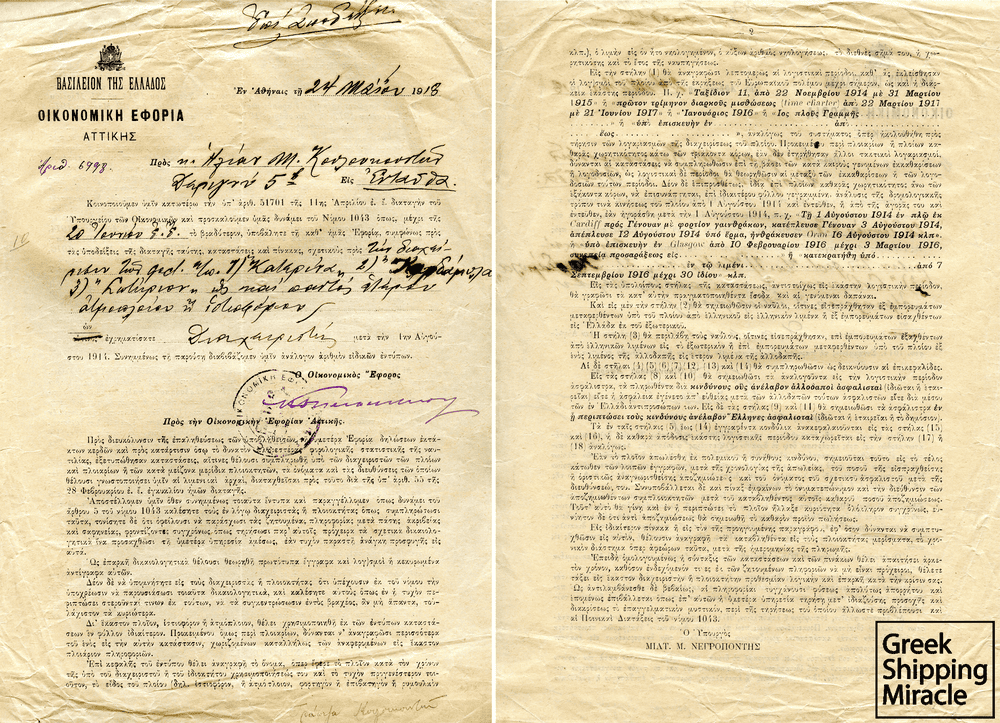

However, the Greek government had different ideas. From November 1917, a heavy retrospective tax was imposed on all shipping revenues dating back to 1915. This referred to all profits materialised through the sale, chartering as well as any insurance money paid to owners for war losses. Venizelos, who was re-elected Prime Minister, in his distress to see the Greek fleet rising to pre-war levels as quickly as possible, had a special decree incorporated in the same tax law. According to this, every owner replacing his steamship within a period of five years after the end of the War would be exempted from that particular tax. This decree, whose time limit was reduced from five years to two in 1919, led many owners to the hasty decision to invest most of their profits at the wrong time. This proved catastrophic for the majority of them, as well as for the industry, as it led to the rapid deterioration of its quality standards over the next few years.