From a War to a Crisis (1919-1929)

At the end of the First World War, even though Greece was among the victors, it did not manage to capitalise on Venizelos’ decision to join the triple Entente and translate the victory into long-term profits. His vision to recover Greece’s territory had been achieved, but he unexpectedly lost the elections in November 1920. This led to an extremely tense and divided political environment that troubled and disorganised the country as 20 consecutive cabinets were sworn in before Venizelos returned to power in July 1928. During this period, Greeks suffered the tragedy of the Asia Minor destruction, which affected Greece in an immense way for many years.

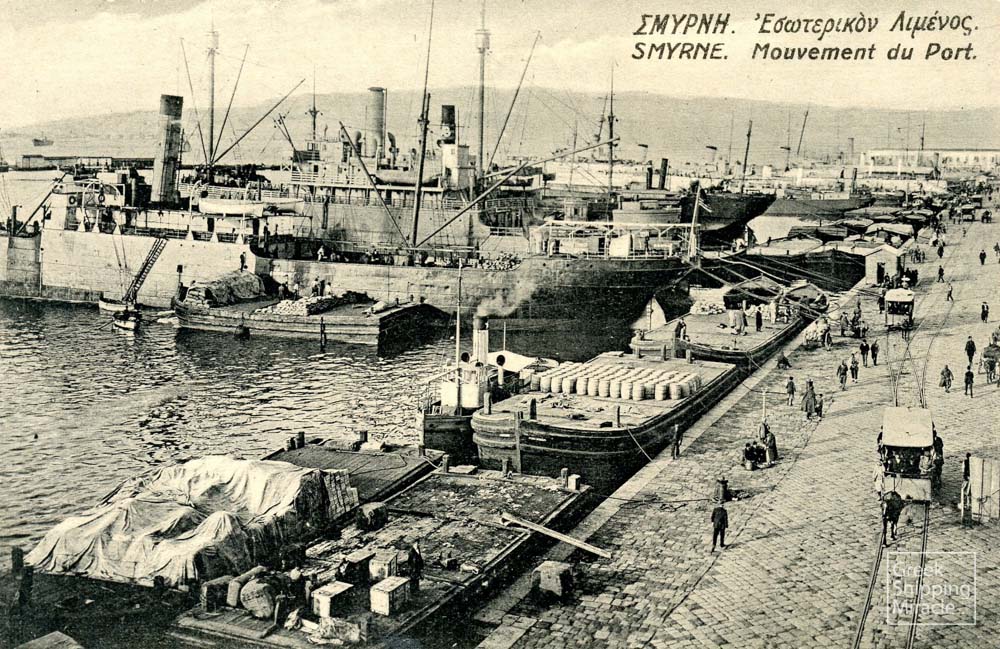

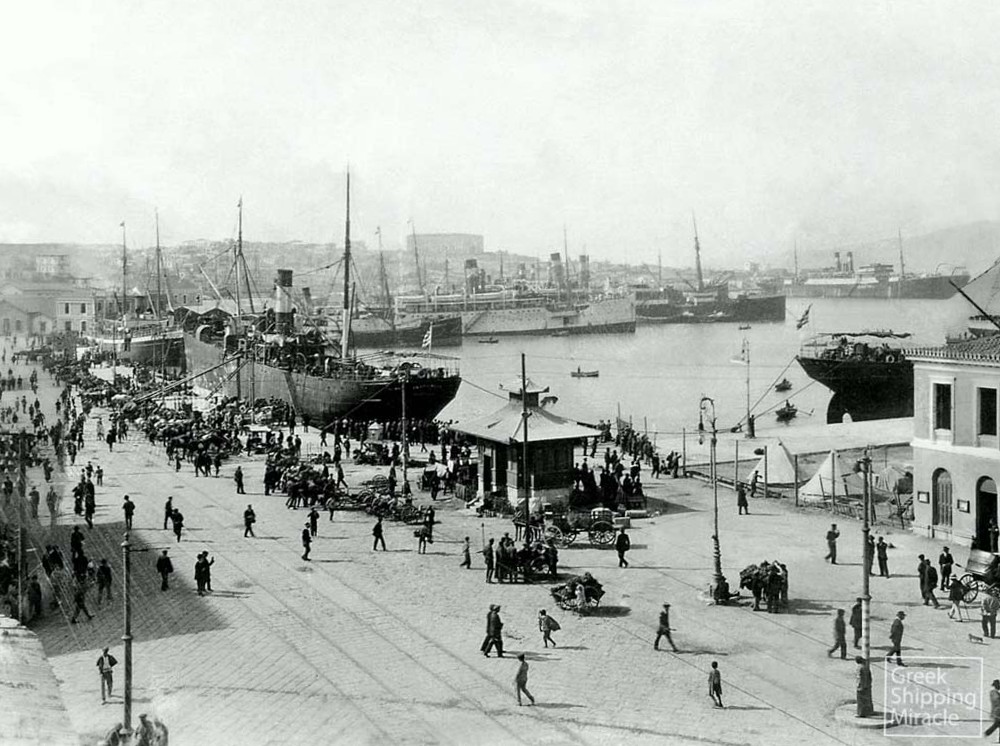

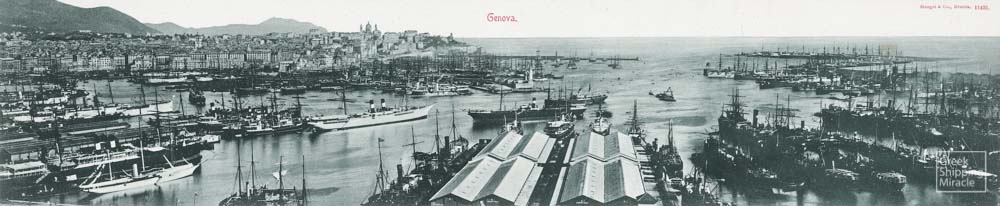

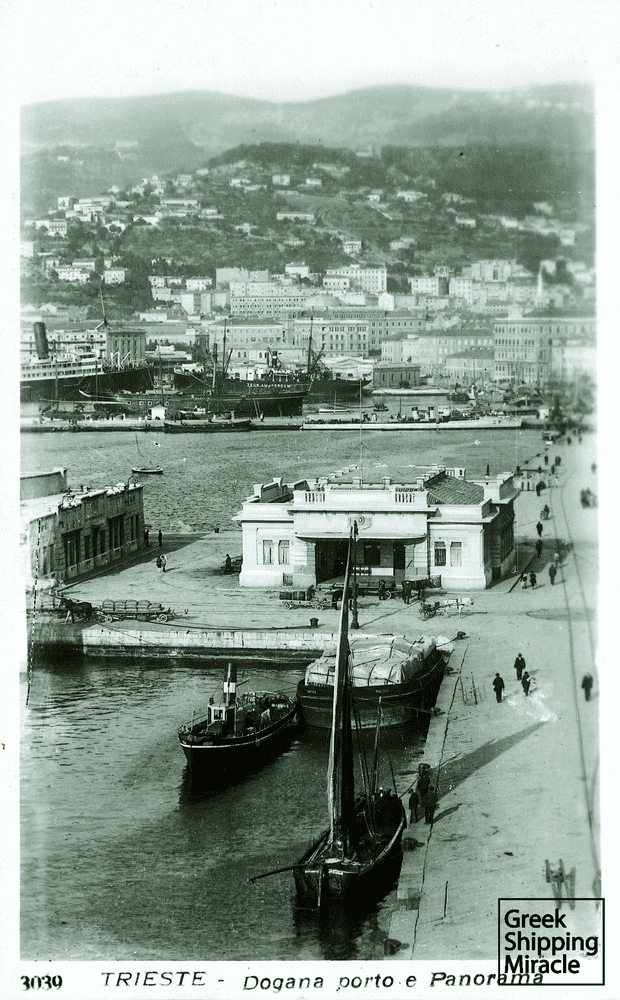

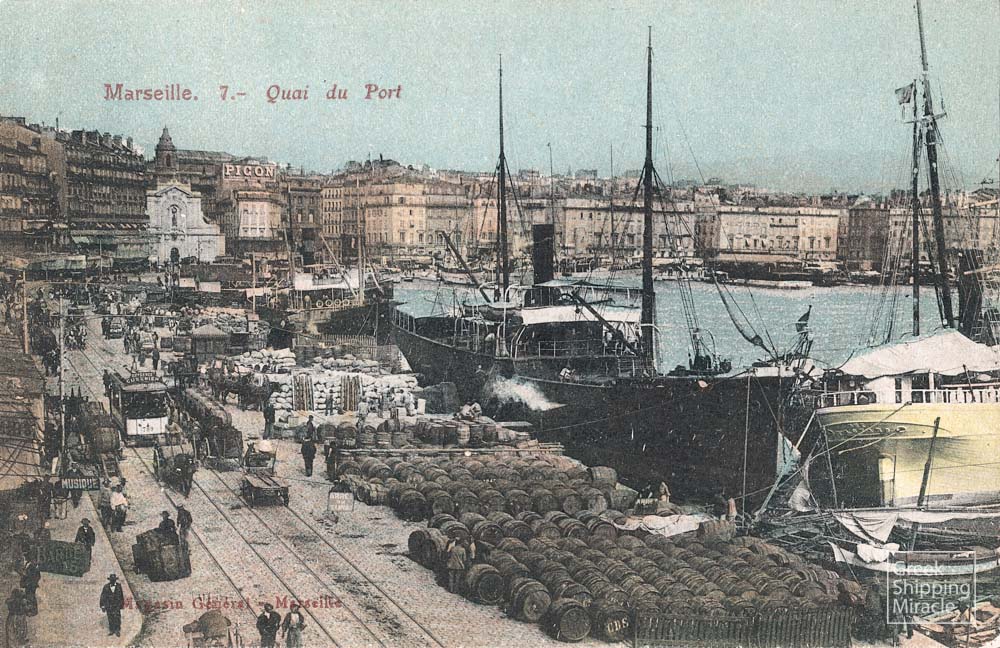

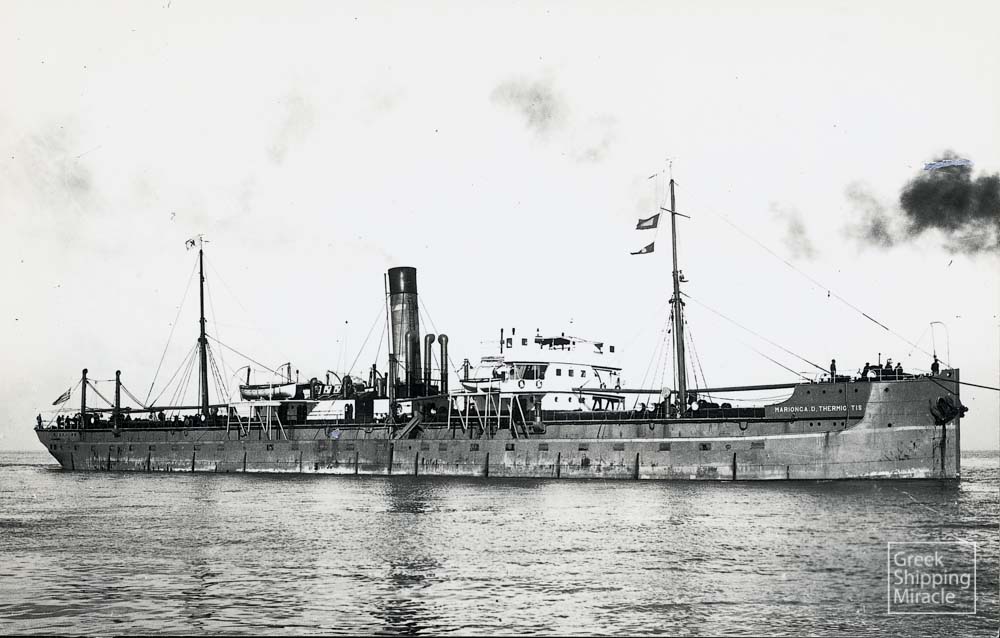

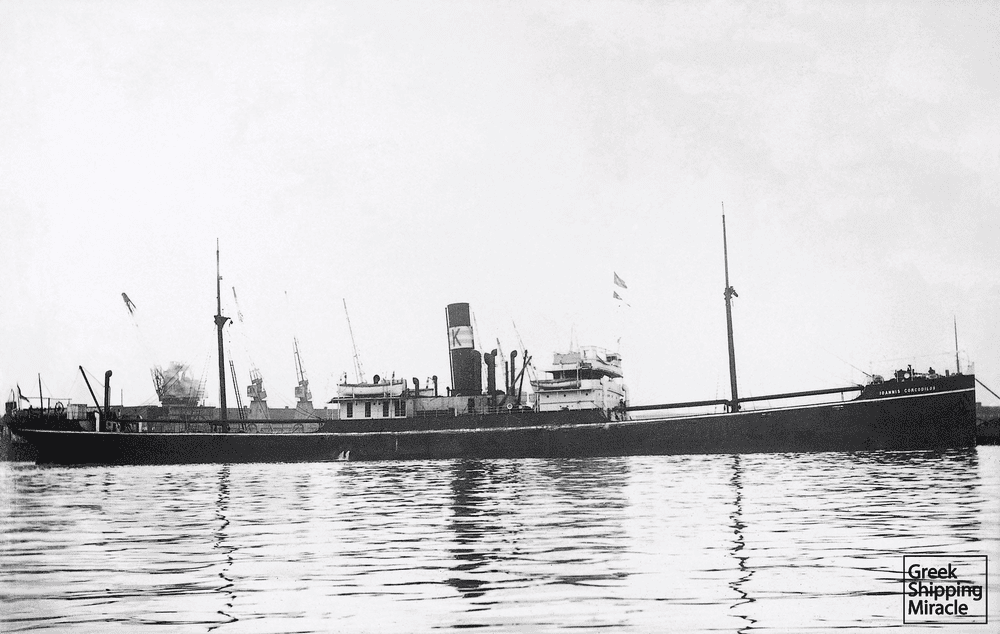

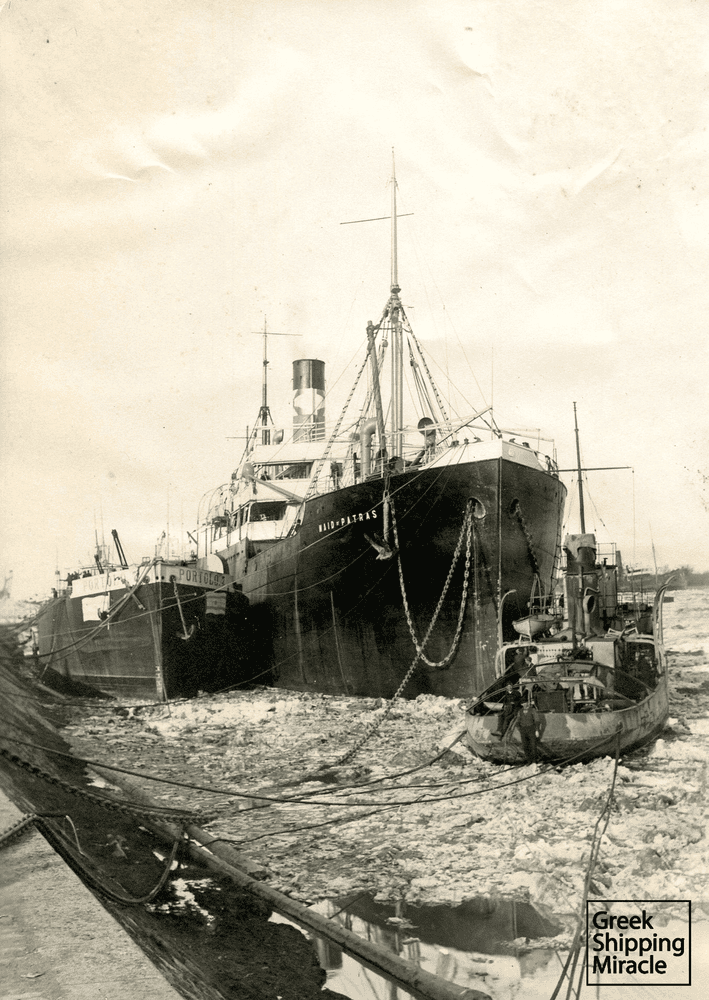

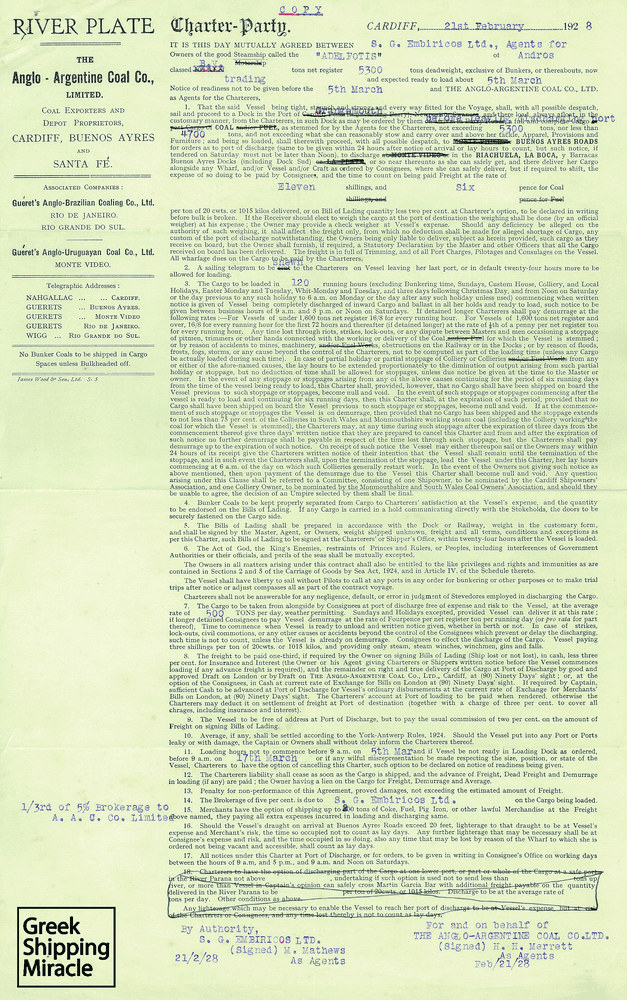

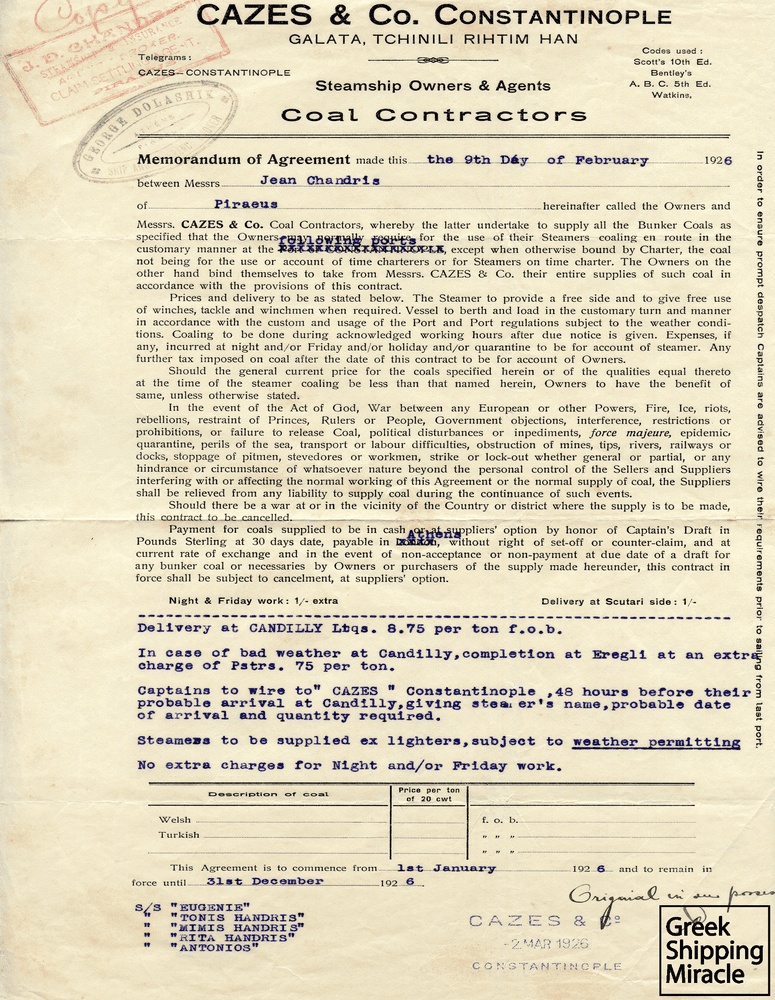

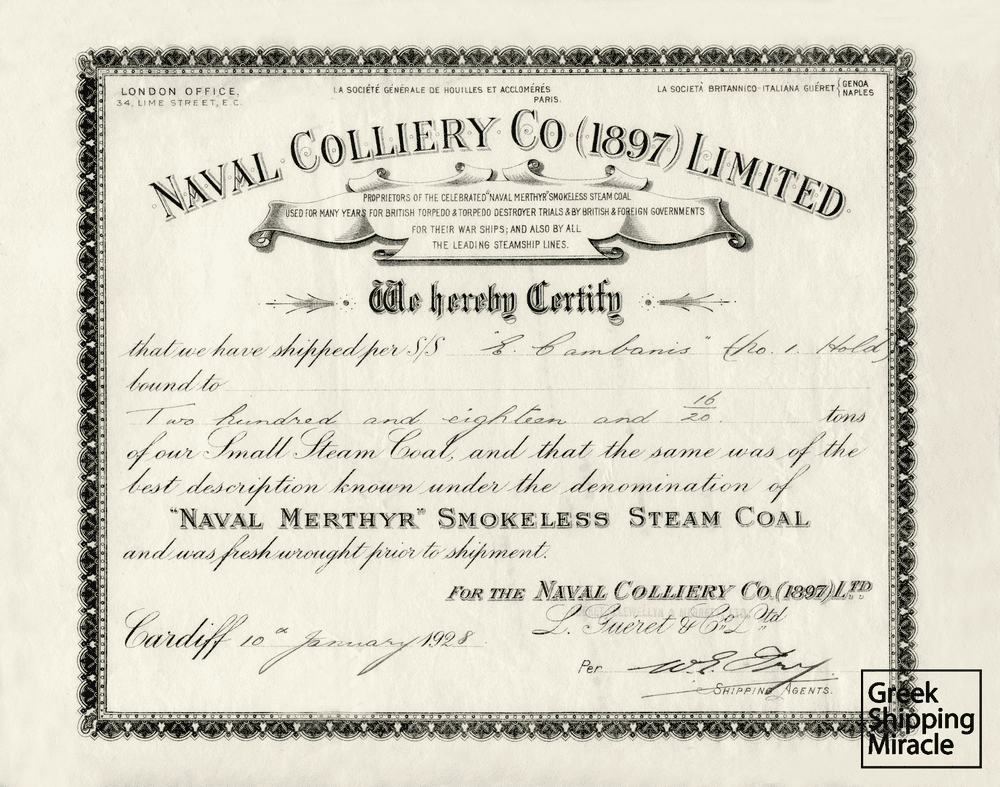

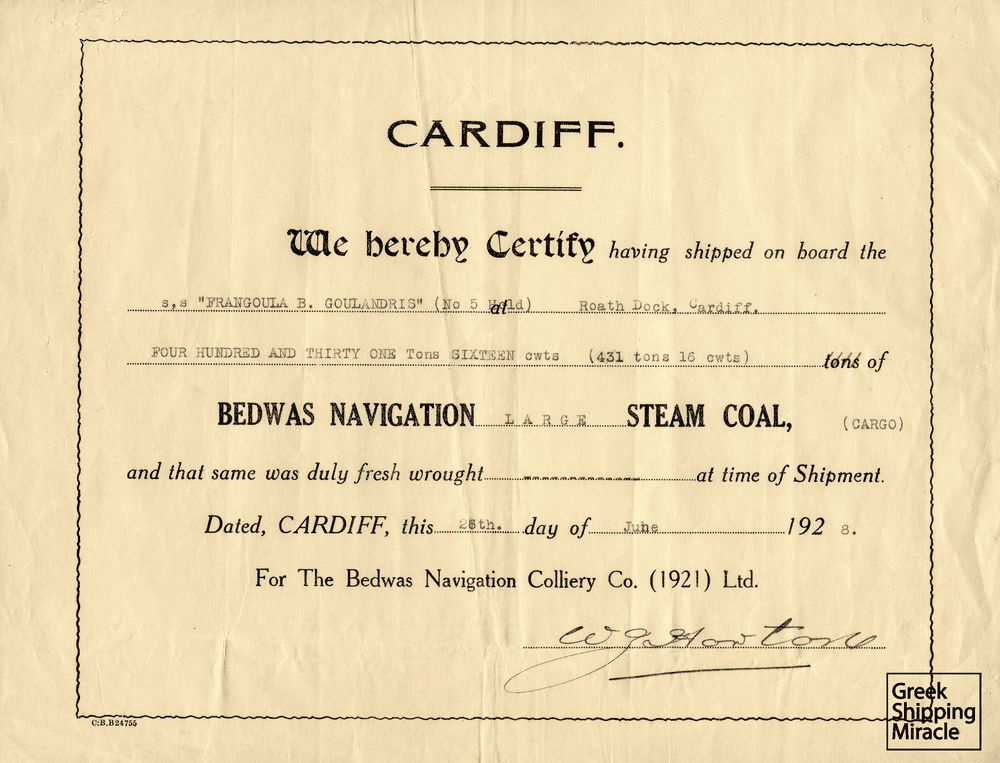

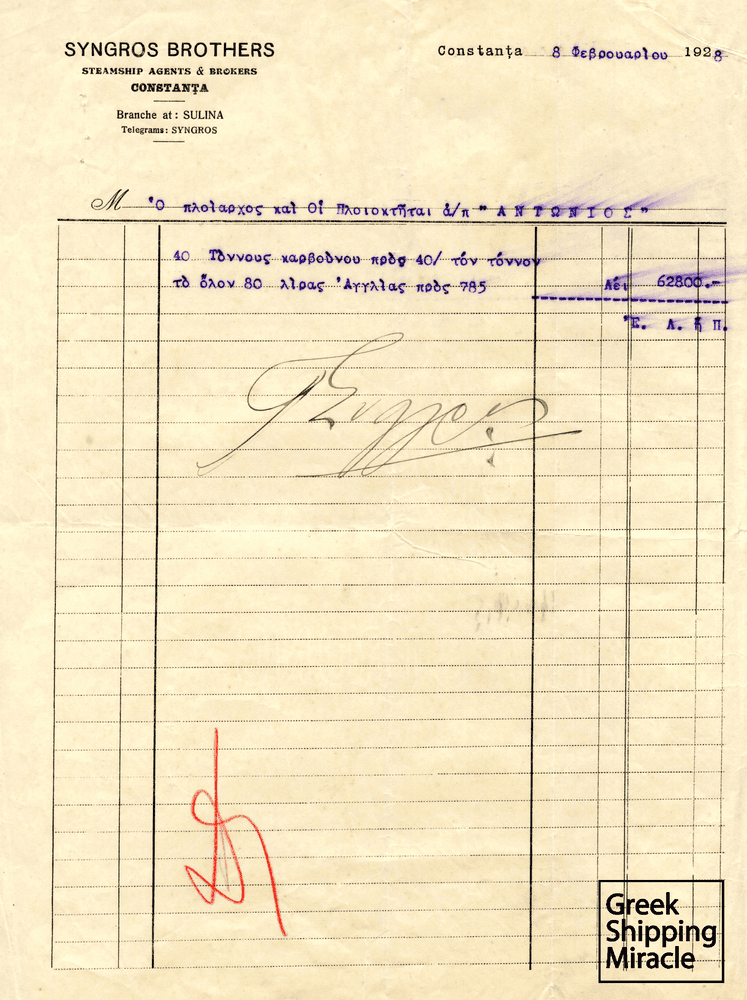

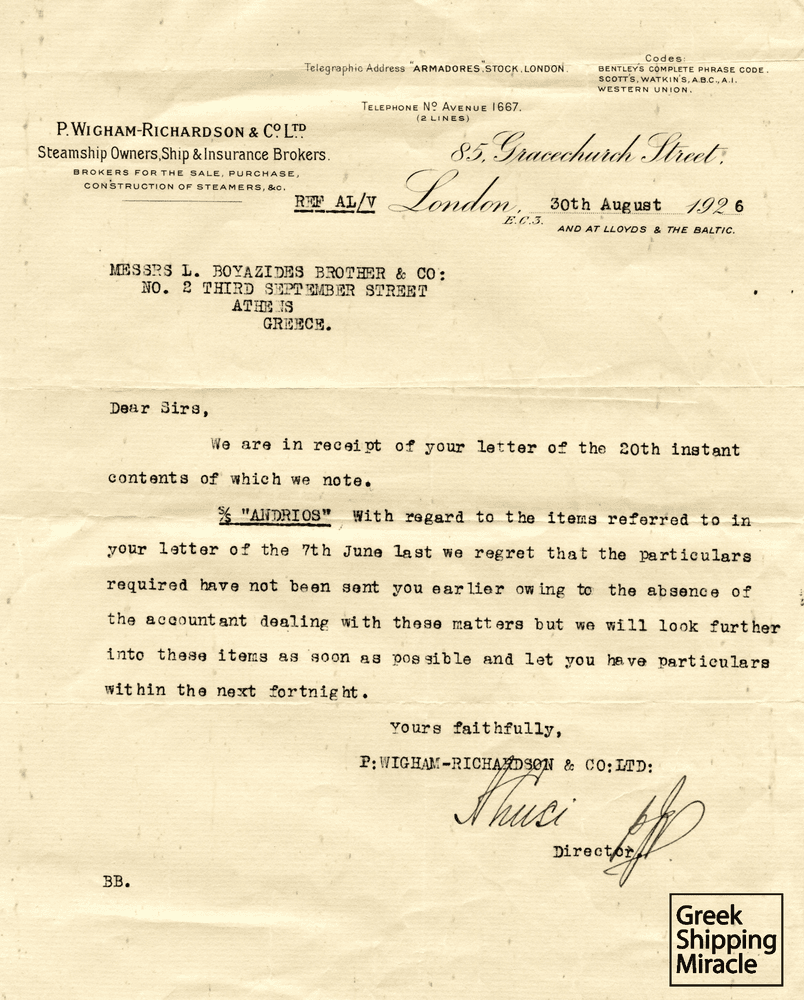

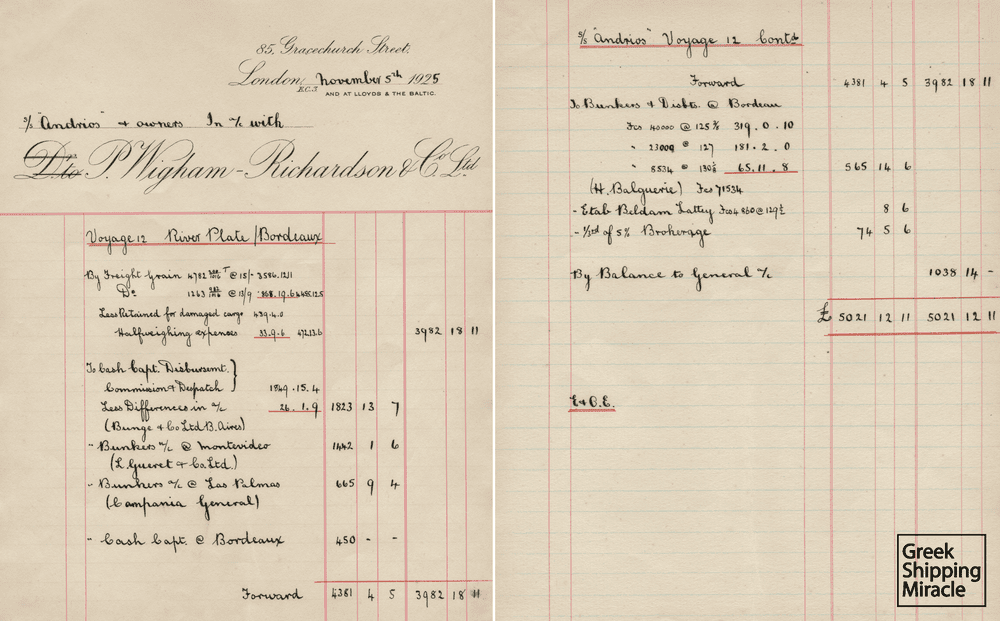

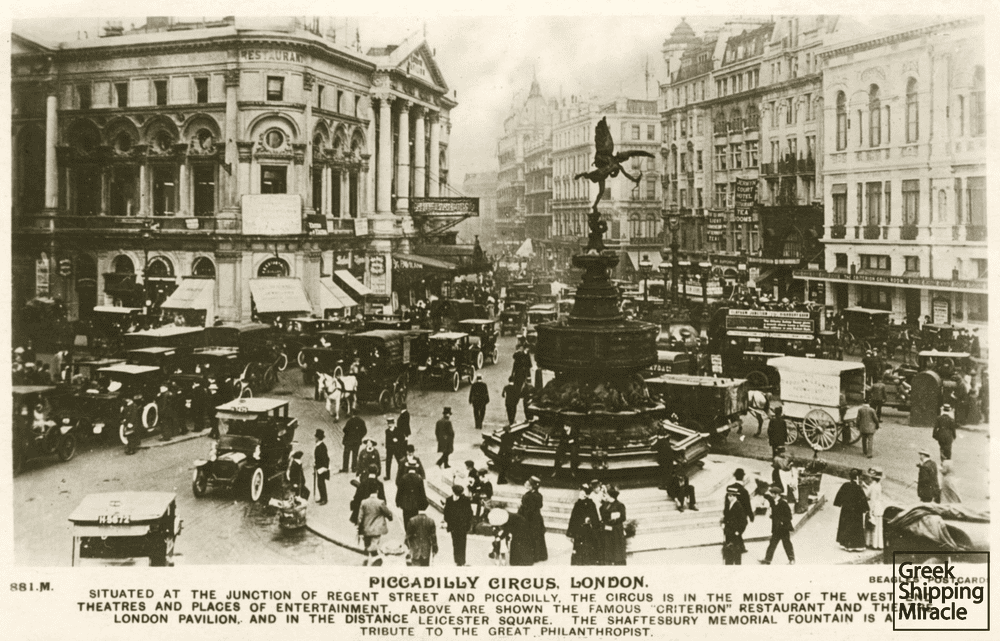

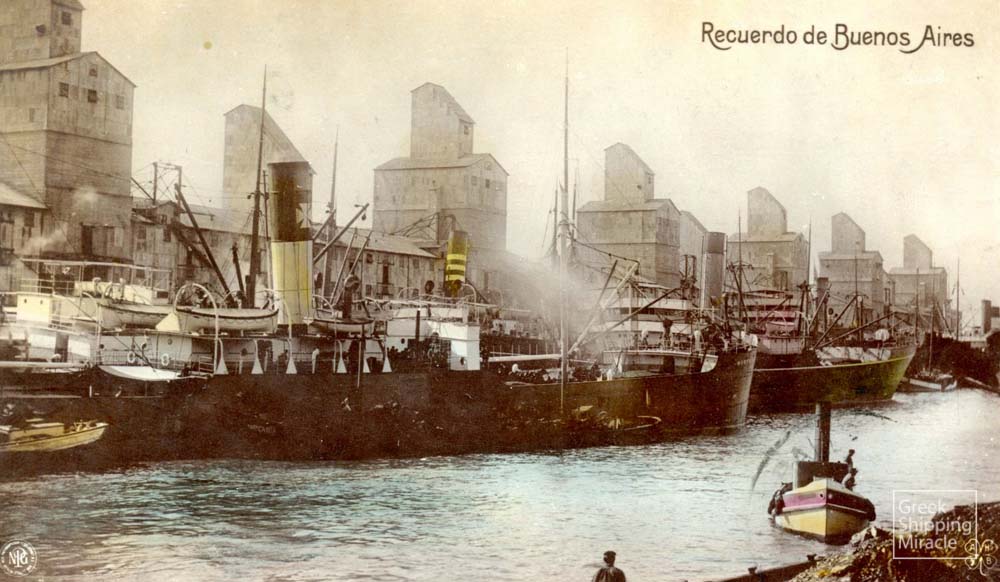

On the other hand, the First World War put the Greek merchant fleet through a great ordeal. Further to the decimation of the fleet during its course, a new operating environment for the shipping industry was established after its termination. Of particular interest was the change that occurred following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the overthrow of the tsarist regime that gave way to the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. This development created a new status quo in the transportation of goods in the Black Sea, a place where a large part of the Greek fleet had traditionally operated until the outbreak of the War. Consequently, Greek shipping had to diversify its operations to other geographical destinations and markets such as the transportation of coal from the United Kingdom to Italy, and mostly to South America, where ships were returning to Europe with grain cargoes. This important change was facilitated by the presence of Greek offices in London, whose number began to increase during the post-war years, after many Greek owners decided to settle in the British capital.

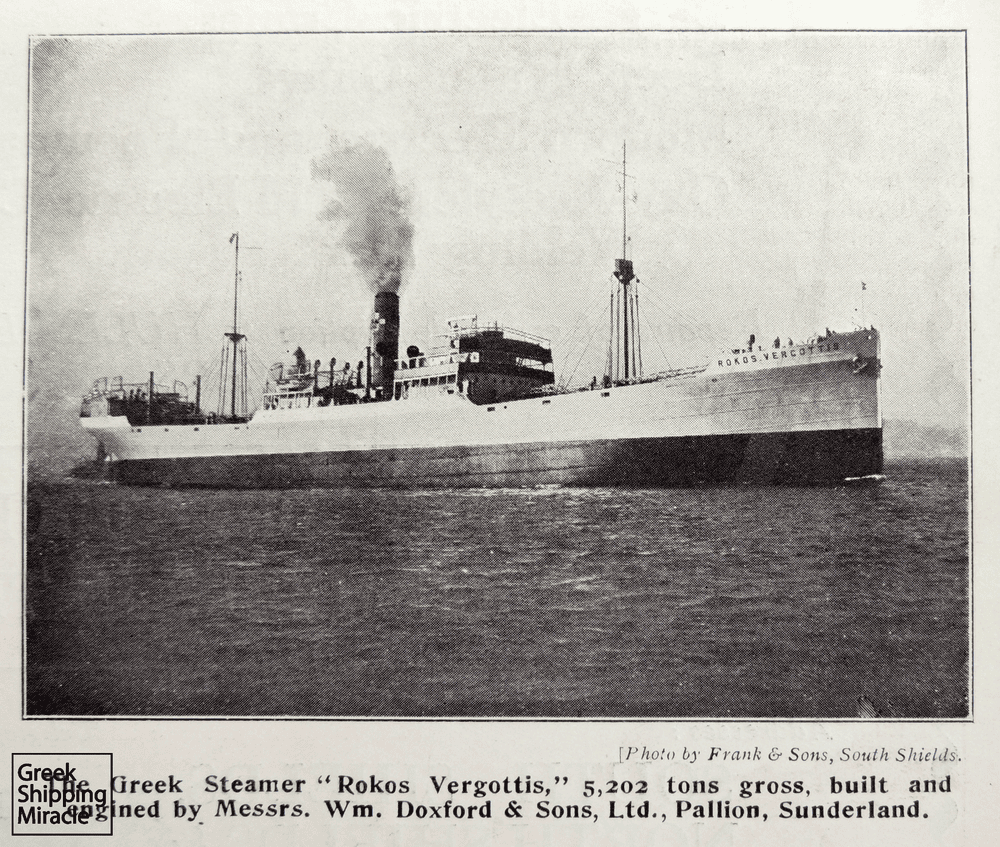

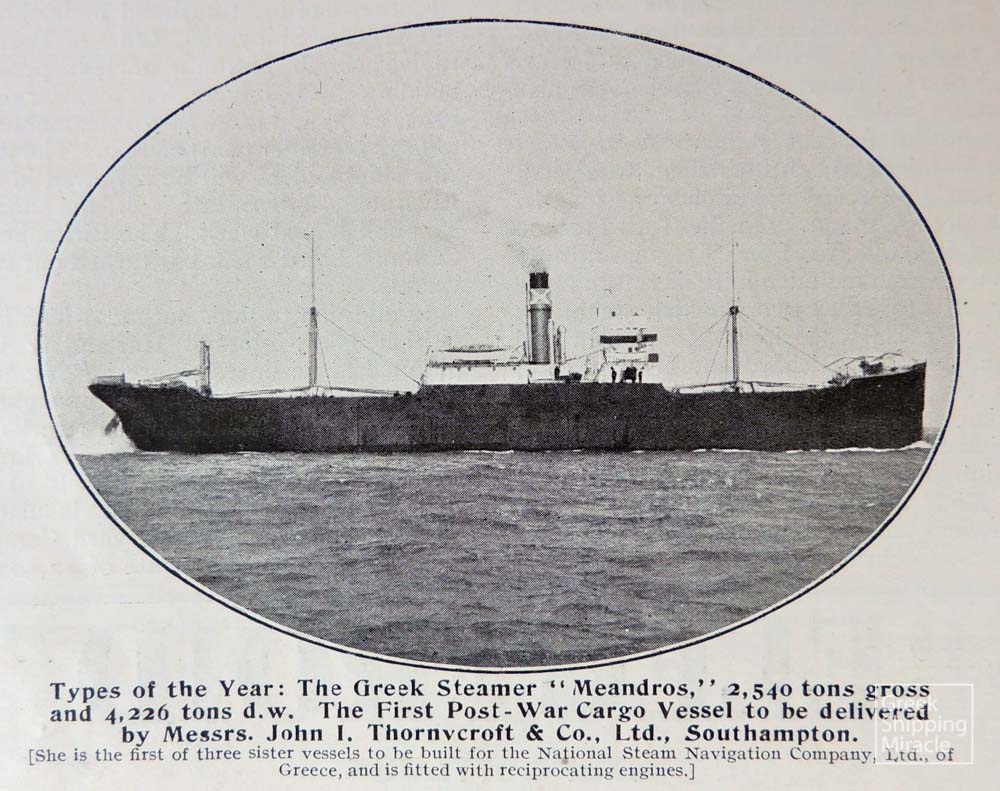

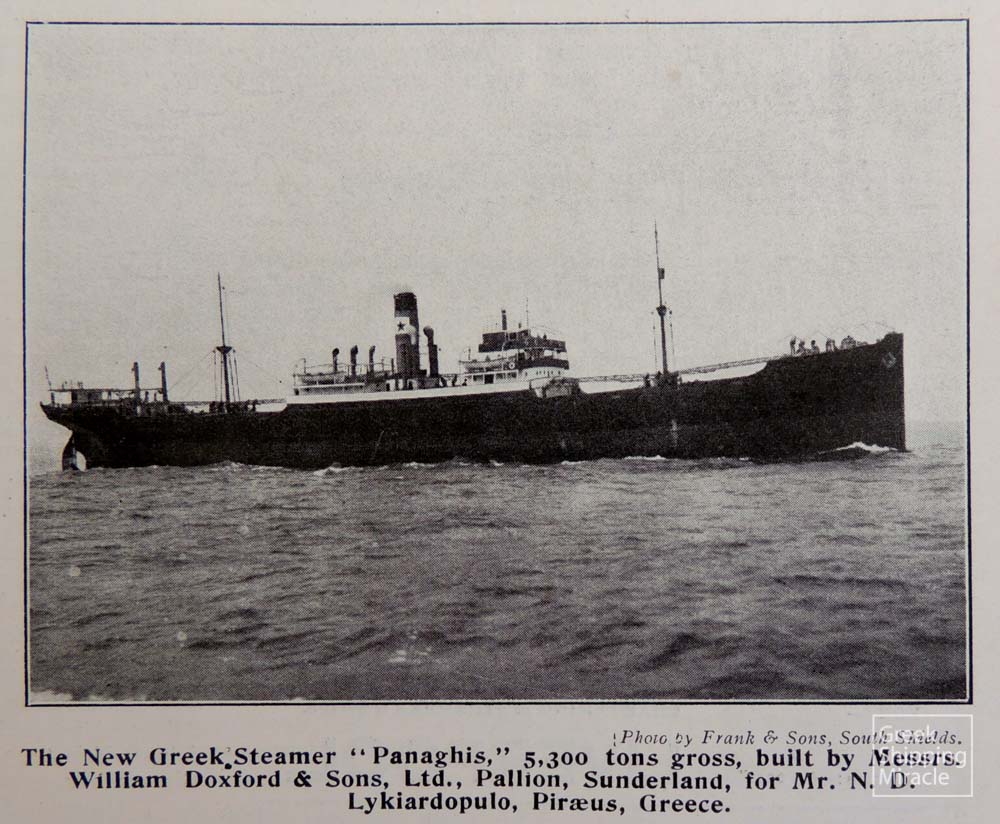

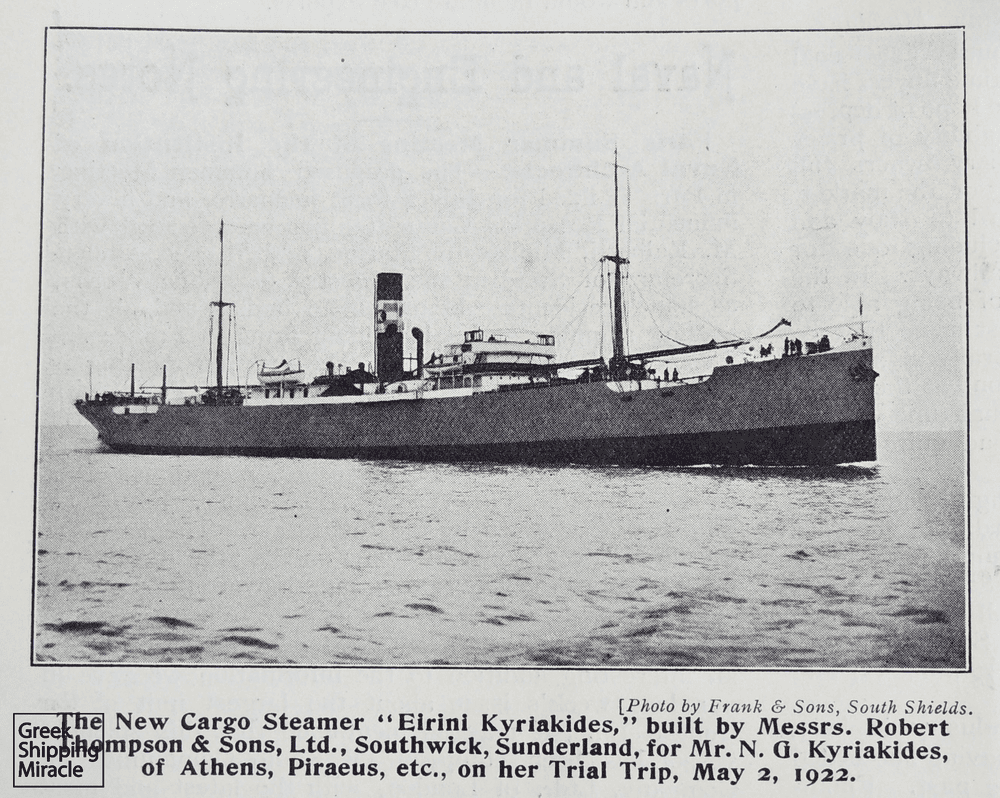

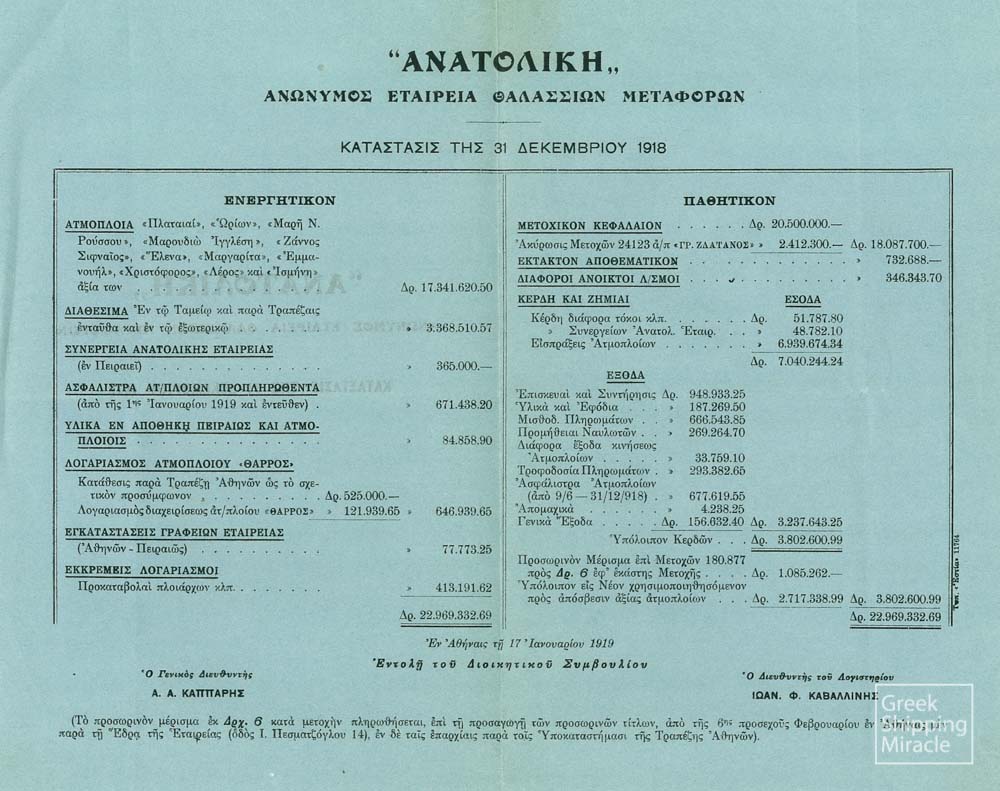

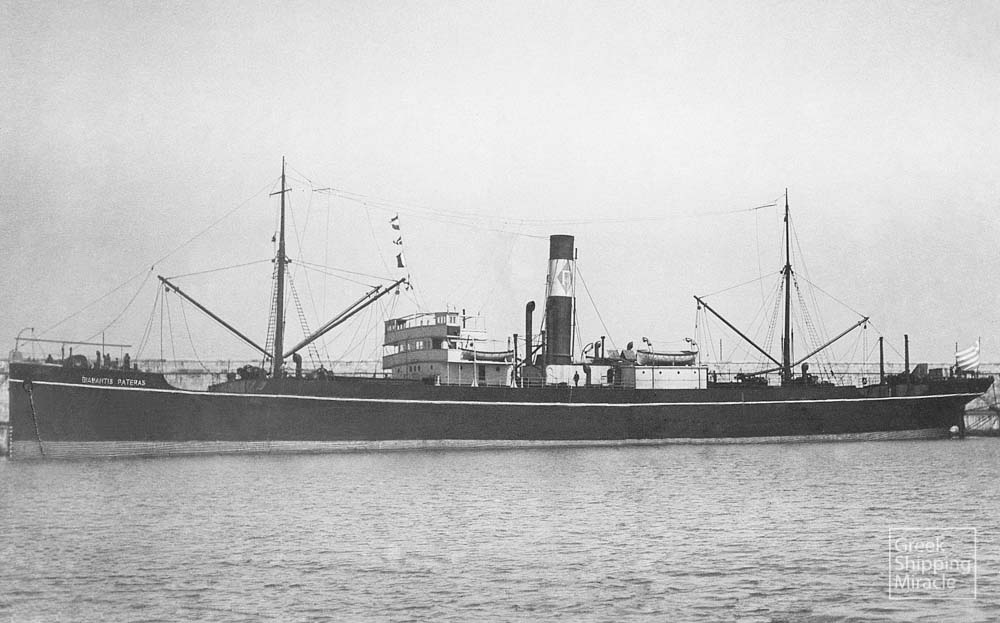

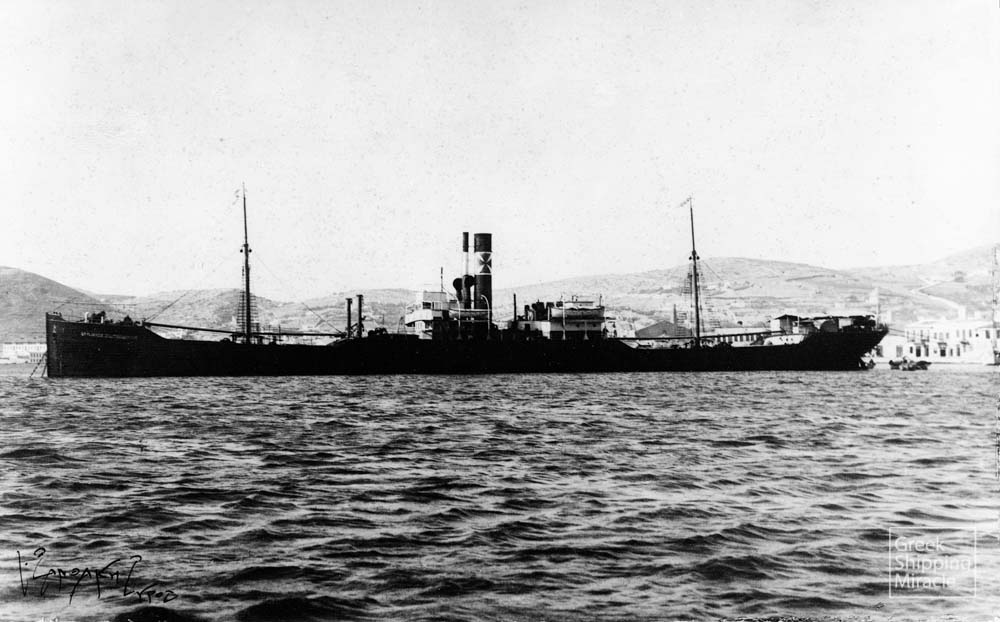

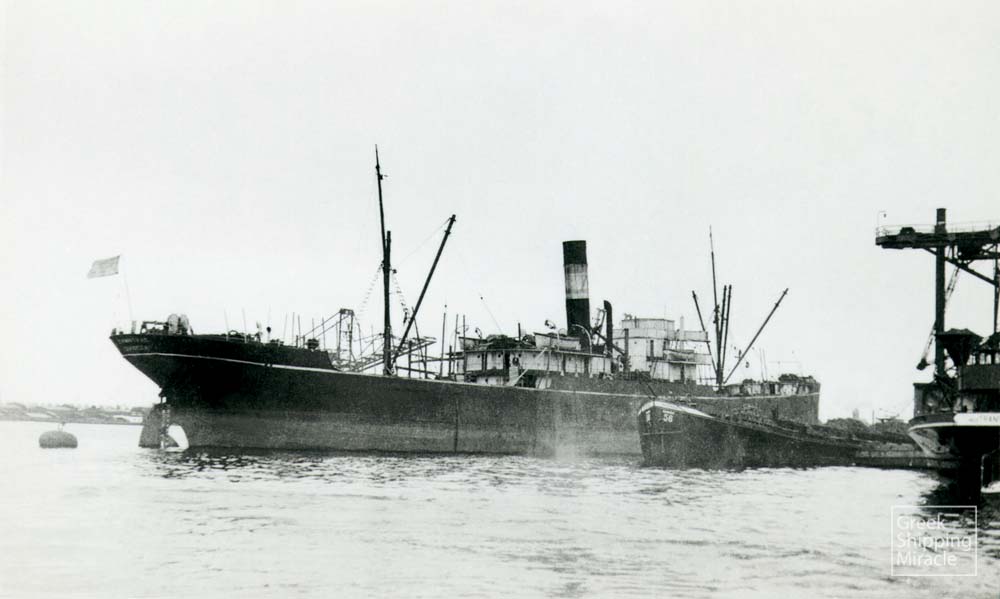

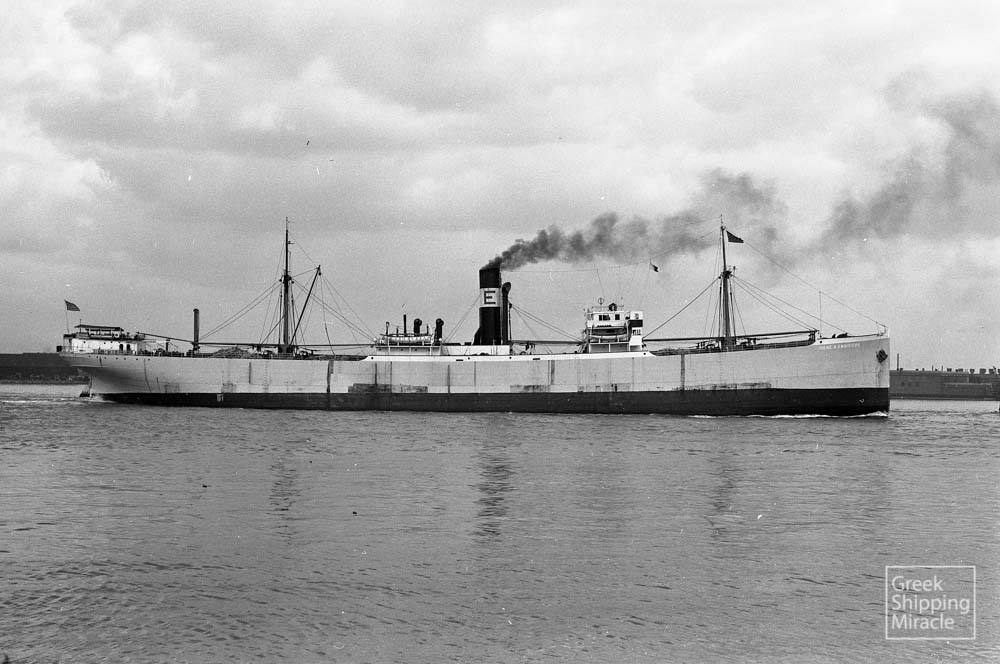

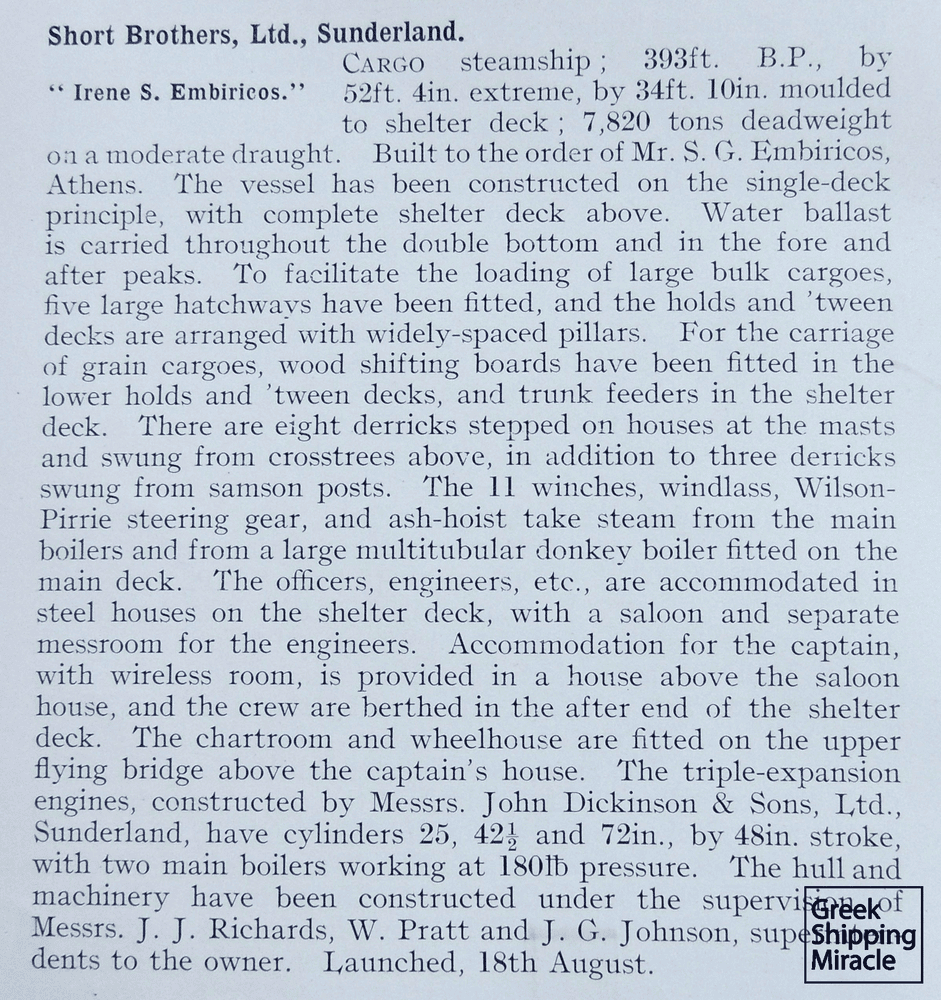

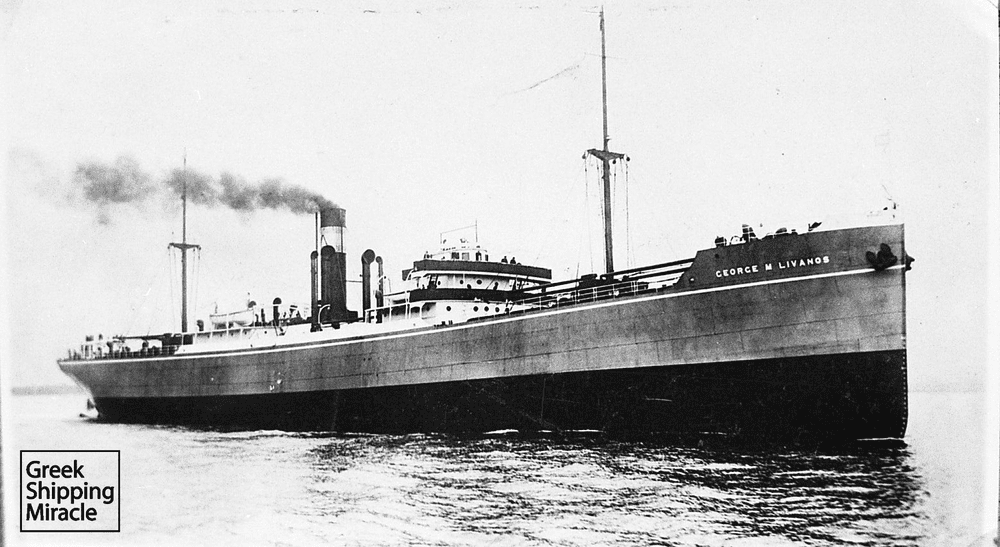

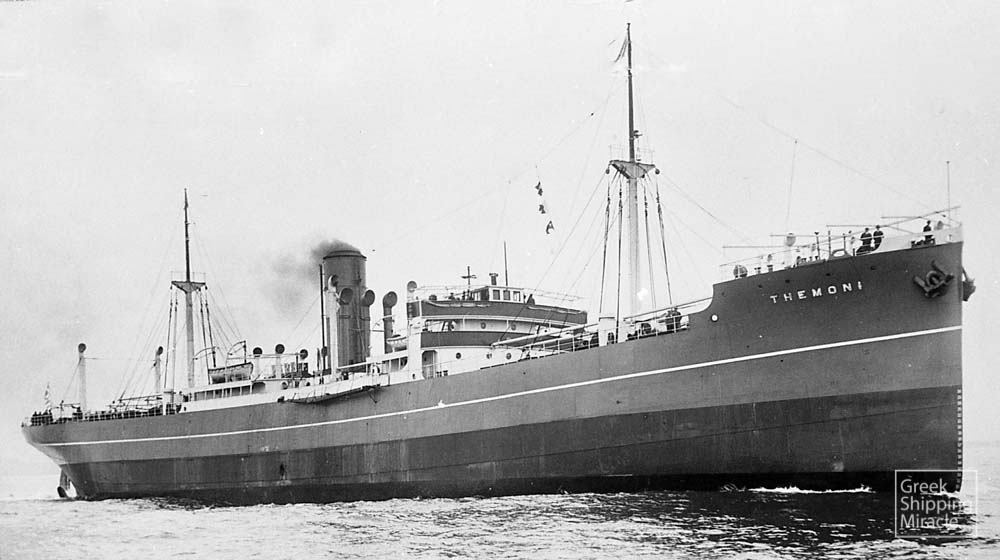

The strict time limits set by the government for the replacement of lost tonnage, in its effort to motivate owners by offering exemption from the retrospective taxation imposed on all wartime shipping revenues, had adverse results. Greek shipowners rushed to acquire second-hand steamers at the exorbitant prices that were established during the War and maintained after its termination due to continuous demand. Even worse, some of the most prominent and financially strong Greek shipowners turned to British shipyards to place orders for the construction of new vessels.

The period of prosperity for the shipping market did not last long. By late 1921, the value of steamers started dropping at an extremely fast pace. Most of the vessels that had been acquired just after the War, either newbuildings or second-hand, lost up to 90% of their value. Many shipowners saw their business in ruins. Others were forced to cancel orders and consequently had to pay substantial compensation to shipyards. It is estimated that about 15 million pounds were invested by Greeks at the time for the acquisition of new or second-hand tonnage, of which 12 million was eventually lost.

However, there were those who benefitted from this situation. These were either prudent owners, who correctly anticipated that it was not the right time to invest in the immediate post-war period, or others who could not afford to buy vessels at the highly inflated prices after the War. This enabled them to be in an advantageous position a few years later when ship prices radically changed again.

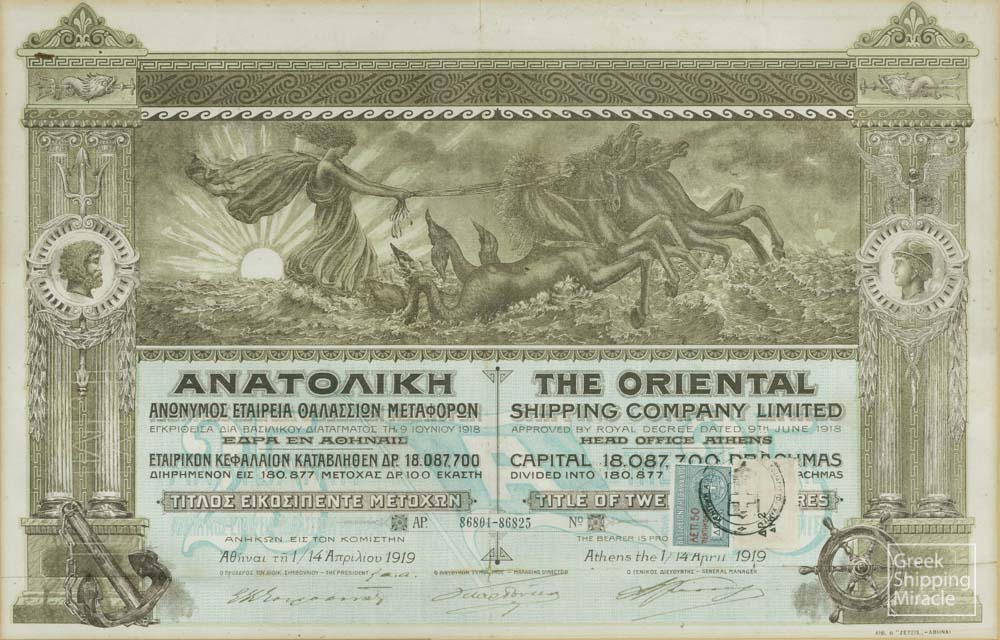

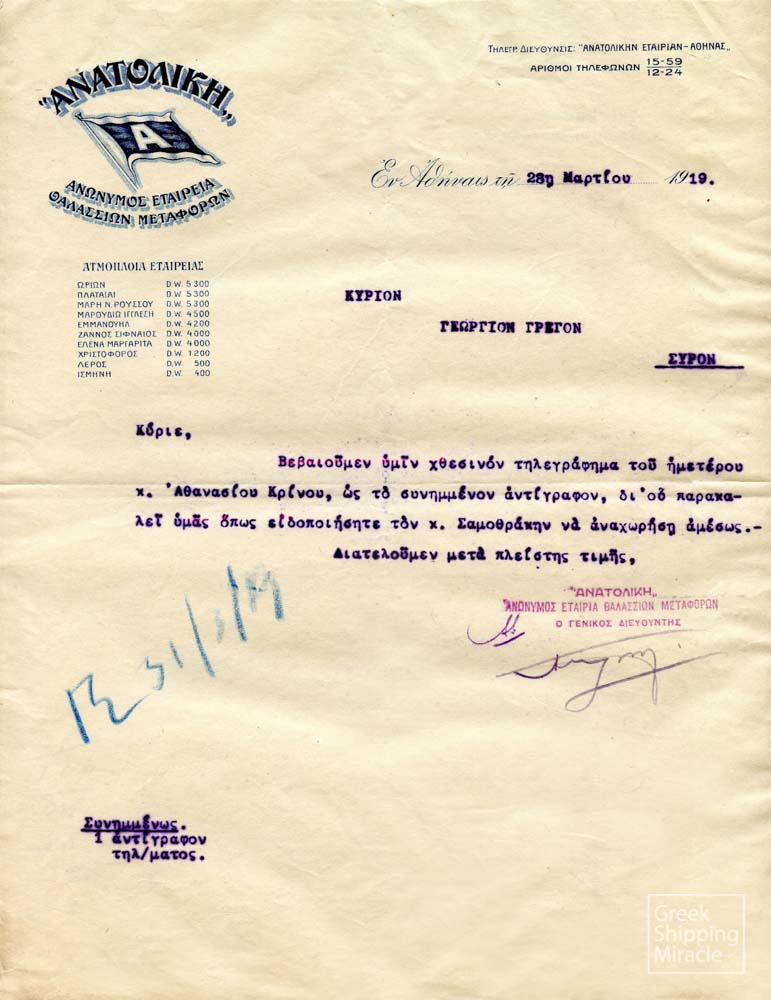

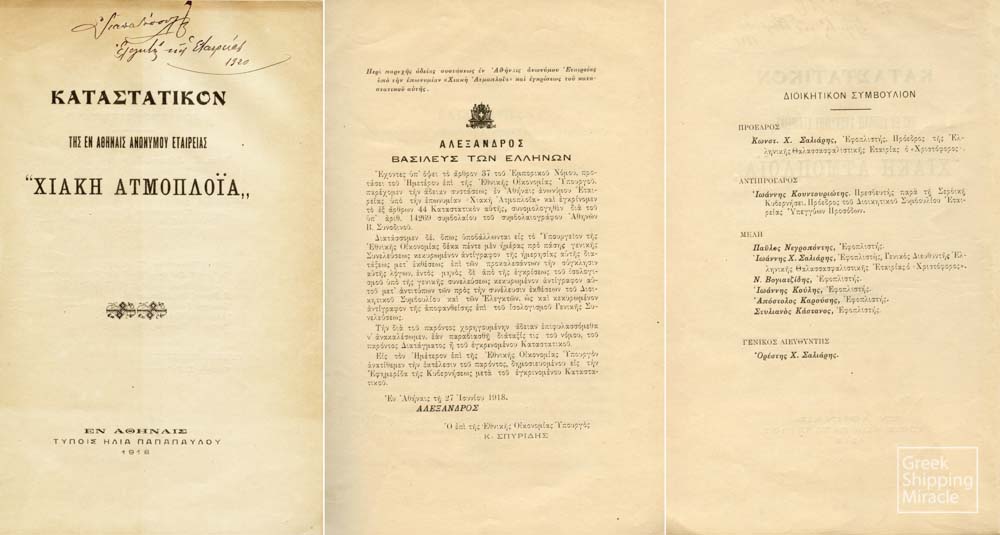

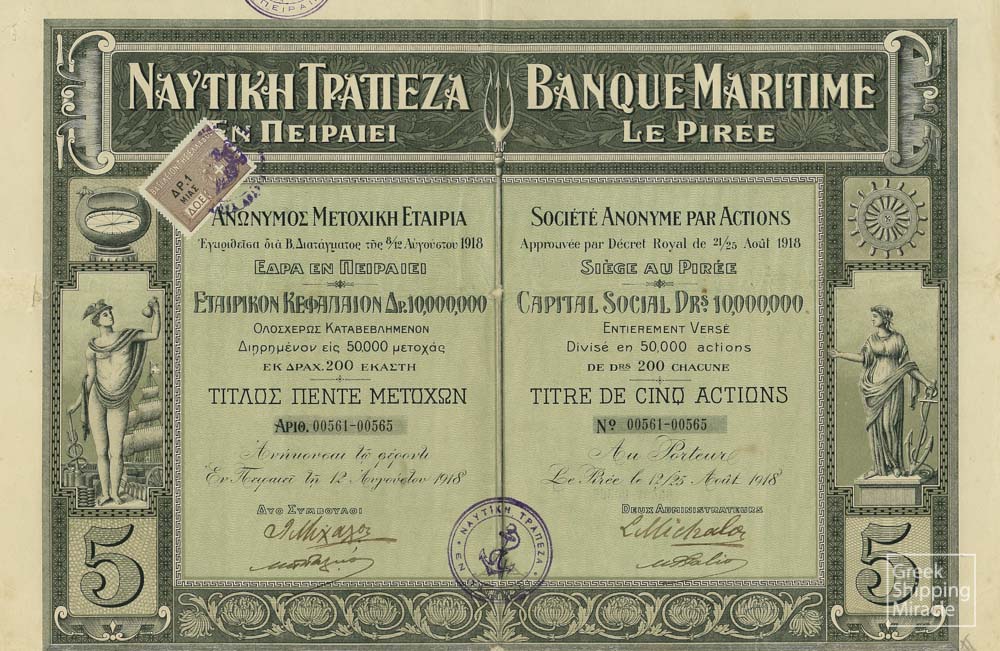

Throughout this time and even before the War ended, the Greek owners tried to address the needs of the industry at home, through the establishment of various enterprises within Greece, especially banks and insurance companies. However, these establishments ended up supporting land enterprises rather than shipping. This occurred because the political developments in the country and the instability in the economy inevitably led many Greek shipowners to maritime centres abroad, especially London. Even the board of the Union of Greek Shipowners ceased meetings following the fall of Venizelos, who despite his heavy tax policy had left a positive mark on the industry with his initiative of establishing the Hellenic Coast Guard in 1919.

The political tension and the rather indifferent attitude of the State towards the shipping industry led to further side effects, damaging the foundation of the industry; the relations between shipowners and seafarers. Several of the latter’s Unions began to be involved in the selection of crews, demanded increases in the number of crew members of steamships as well as other requests. When these were rejected, seafarers reacted with protests and strikes, which caused concern to shipowners, who were struggling at the time to maintain the operation of Greek ships at competitive levels.

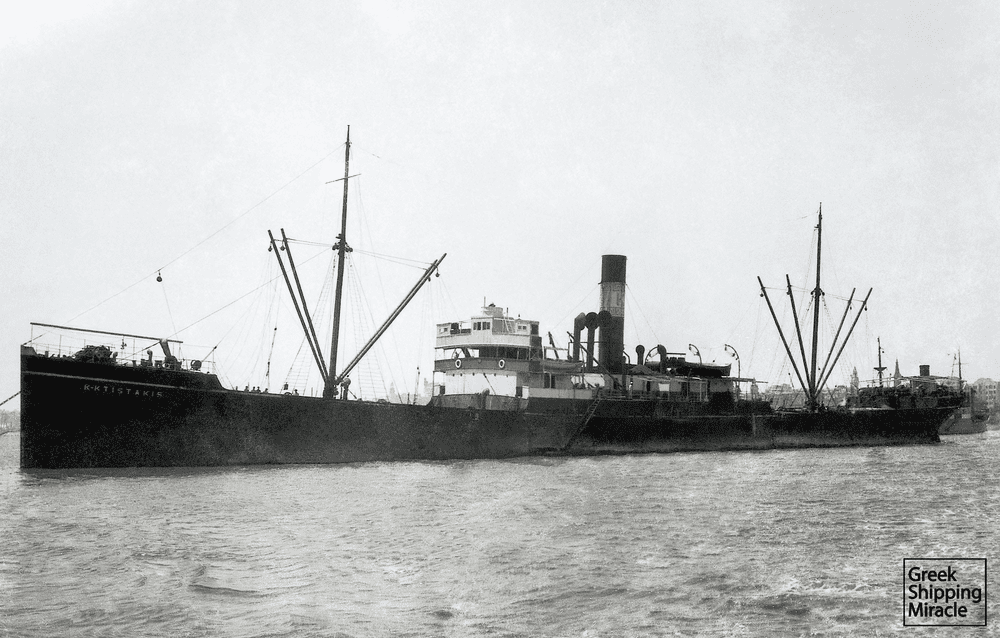

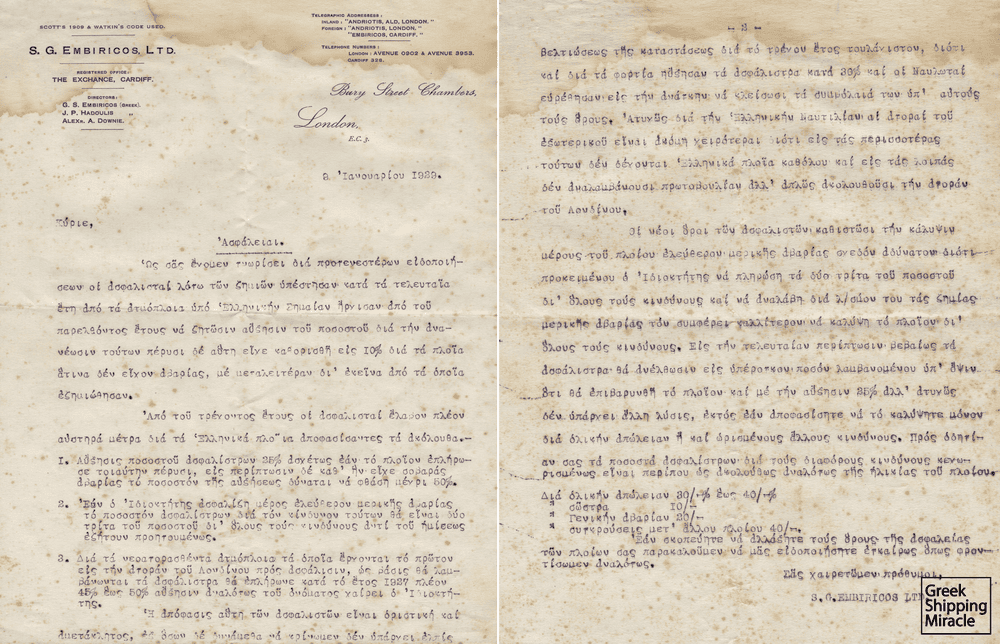

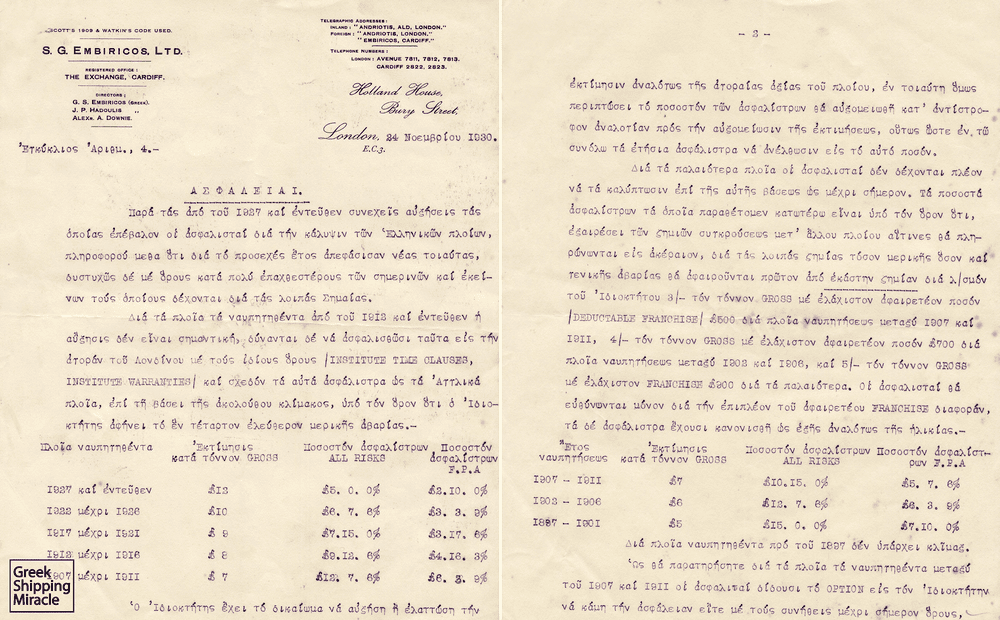

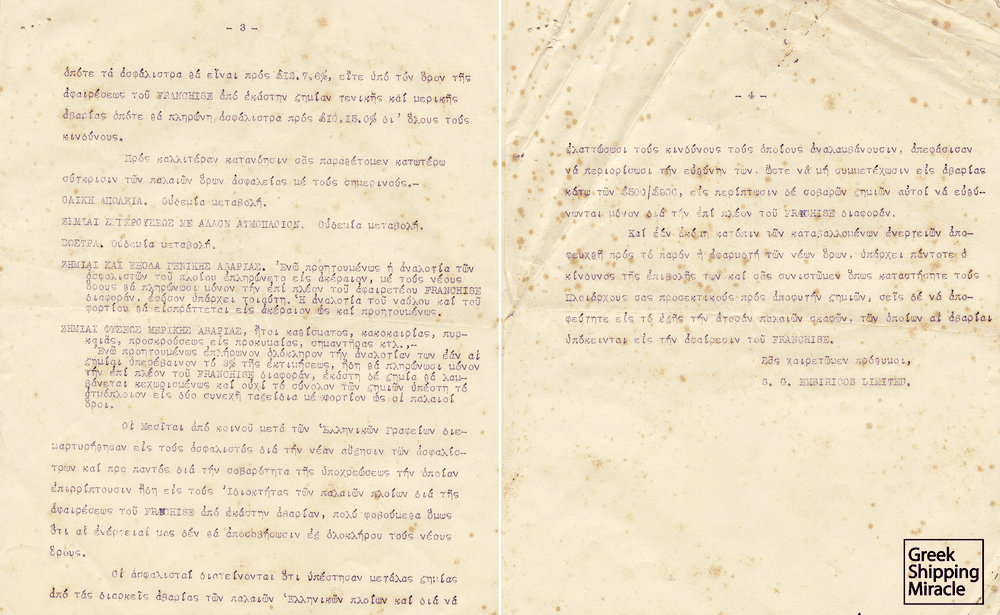

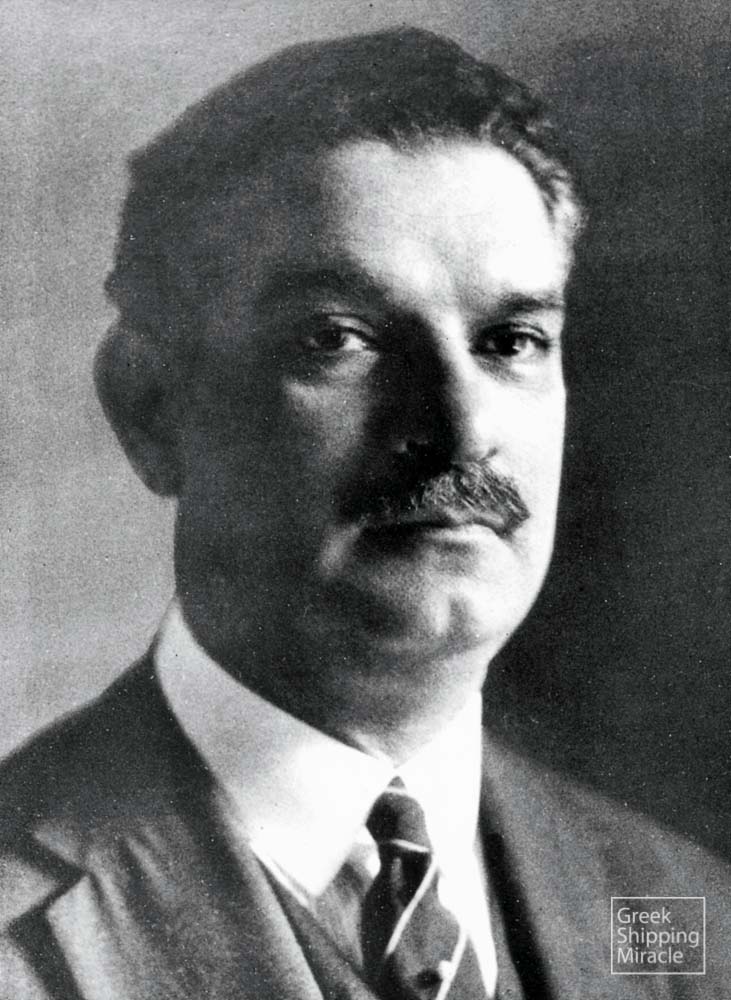

The image of the Greek shipping industry was spoiled even further during 1920-1921. This was due to the actions of several newly established shipowners, who had acquired very old steamers at extremely high prices and eventually lost them under suspicious circumstances. This resulted in the total discrediting of the industry, despite the fact that none of these incidents were related to traditional shipping families. However, this did not prevent British insurers from blacklisting Greek shipping, which took many years and efforts to overcome. At the same time, shipowners realised the need to reactivate the Union of Greek Shipowners. Its operations were resumed in 1924 under the leadership of one of the most respected personalities within the industry, Stamatis G. Embiricos.

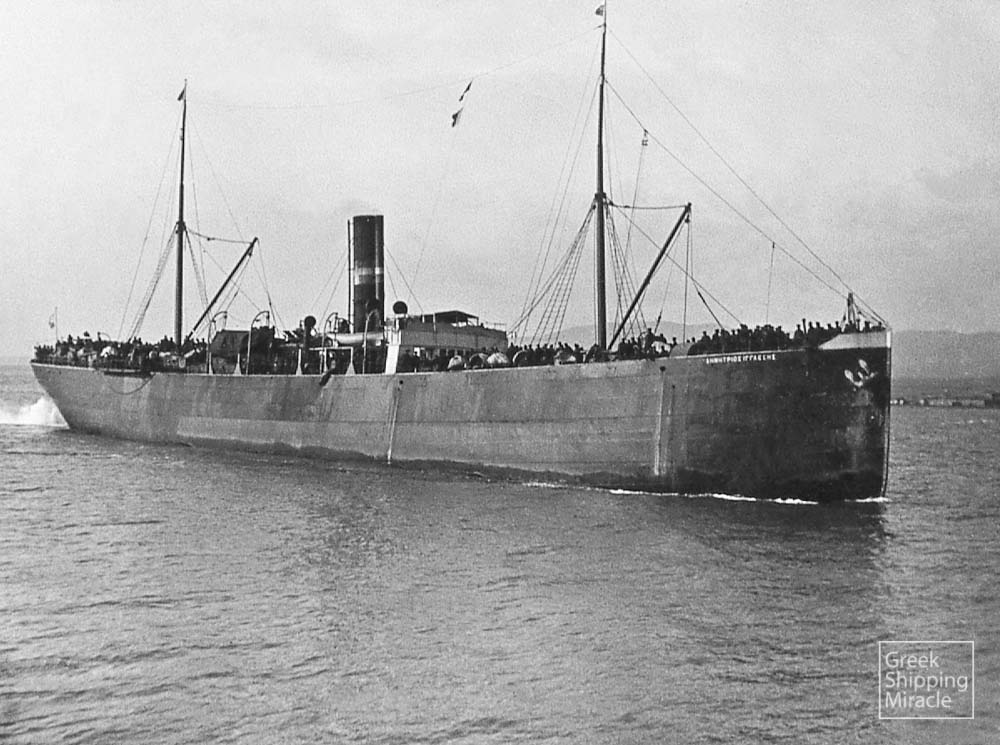

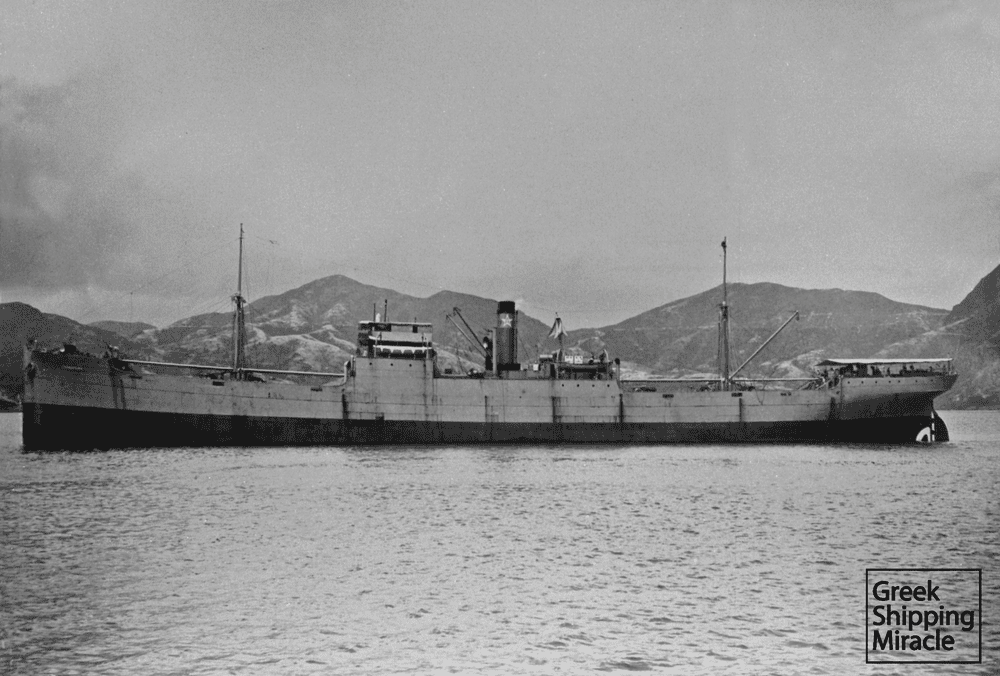

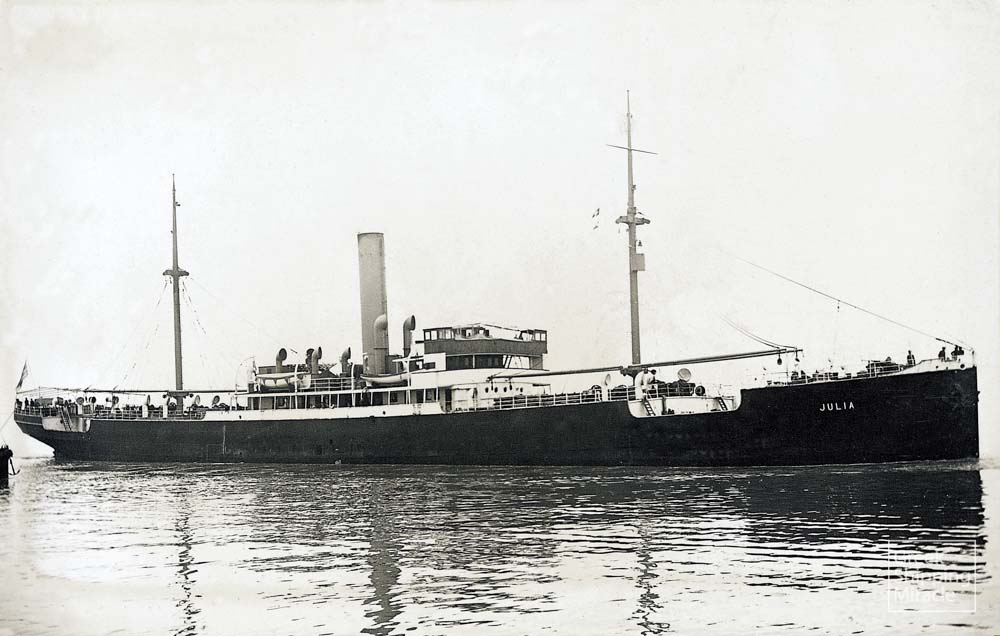

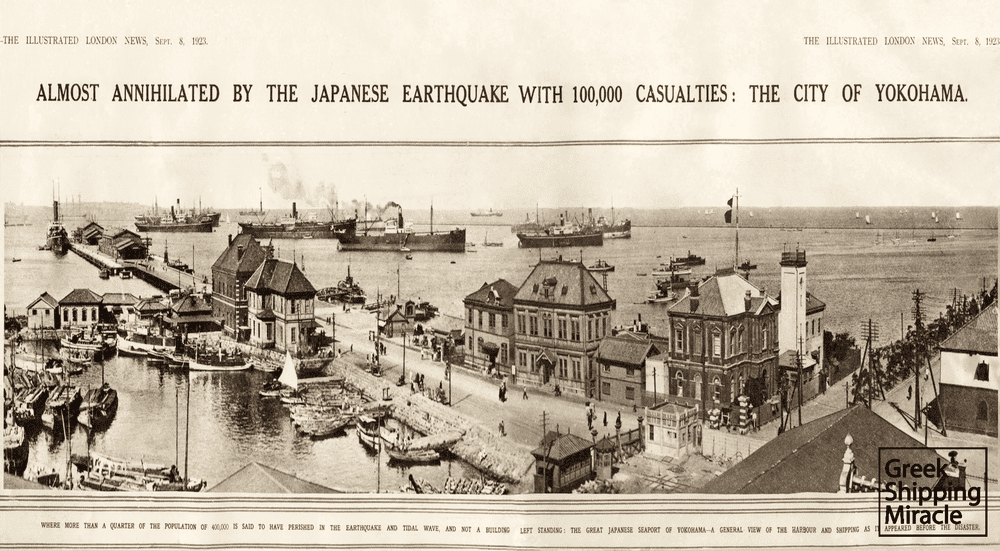

The devastating earthquake in Tokyo on September 1, 1923, and the increase in demand for the transportation of cargoes due to this tragic event, had a positive effect on the market. This led many Greeks to gradually begin investing once more in second-hand tonnage. In 1925, the Greek fleet surpassed the size of the pre-war fleet for the first time; however, it still differed vastly in terms of quality and average age of ships.

Another unexpected development, the British miners’ strike in 1926, led to the disappearance of British coal from the market. This allowed other market players to dynamically develop their production in order to meet the demand of the specific material, which was the main source of energy at the time. Many newcomers in the industry took advantage of the rising market and, with the financial support of their compatriots operating shipping offices in London, managed to acquire steamships, most of which started operating under the command of their new owners.

The continuous progress of Greeks in the industry, and their increasing ability to enter more competitive markets, began to cause concern amongst other competitors. British insurers decided to place higher premiums on Greek vessels carrying grain cargoes from the Argentinian Plate. This problem was overcome after several efforts from a leading personality, Manolis E. Kulukundis, co-founder of the Rethymnis & Kulukundis Ltd., who had significant connections in the London marine insurance market. At the same time, the Greeks returned to British yards. The delivery of several newly built vessels between 1927 and 1930 enhanced the Greek fleet, bringing down its average age.

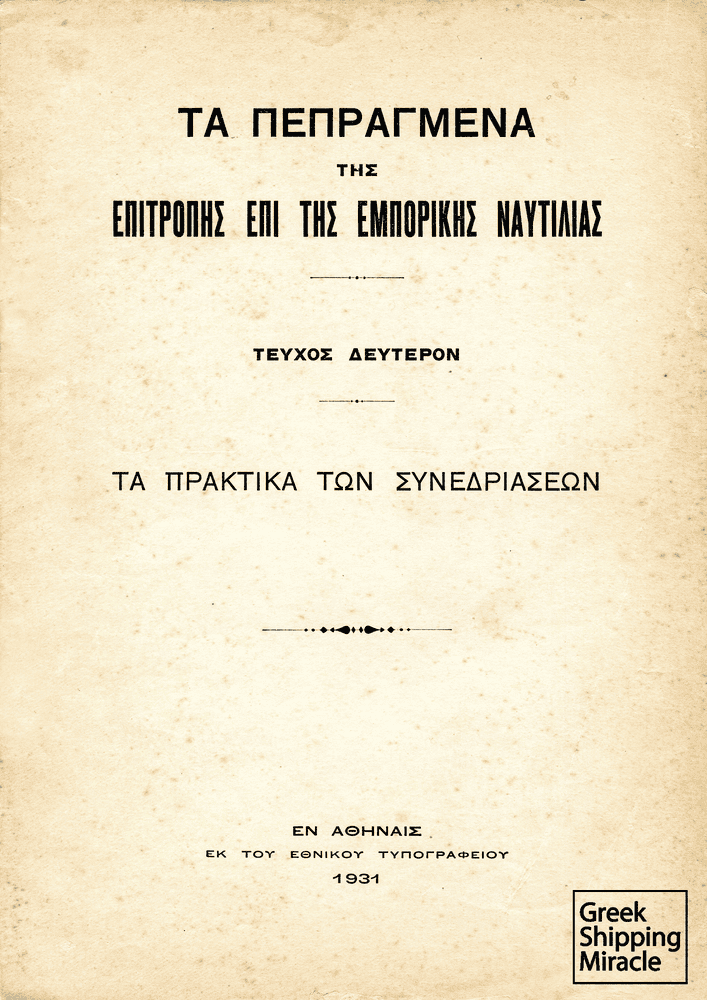

During a time when Greece was trying to find stability after years of devastating civil unrest and divisions, Venizelos found himself once again at the helm of the country in July 1928. Shipowners met with the Prime Minister to brief him on the overall situation of the shipping industry that had diverted the core of its operations to London for some time. Venizelos responded immediately by setting up a committee with members from all political parties, headed by Vice President Andreas Michalacopoulos, in order to study the industry’s problems. Among these were issues arising from policies adopted by the state on seafarers, putting at risk the competitive status of Greek-flagged vessels. In that memorandum, submitted by the owners in September 1929, the possibility of massive re-flagging of Greek ships was mentioned for the first time.

The Committee’s work was a lengthy process. Its conclusions were issued in 1931, but failed to serve anything more than a mere record of the problems encountered at the time. The developments were extremely rapid, as only a month after the submission of the shipowners’ memorandum, the Wall Street Crash on Black Tuesday, 29 October 1929, brought chaos to global economy and consequently to the shipping industry at large.