Decimation of the Fleet (1940-1945)

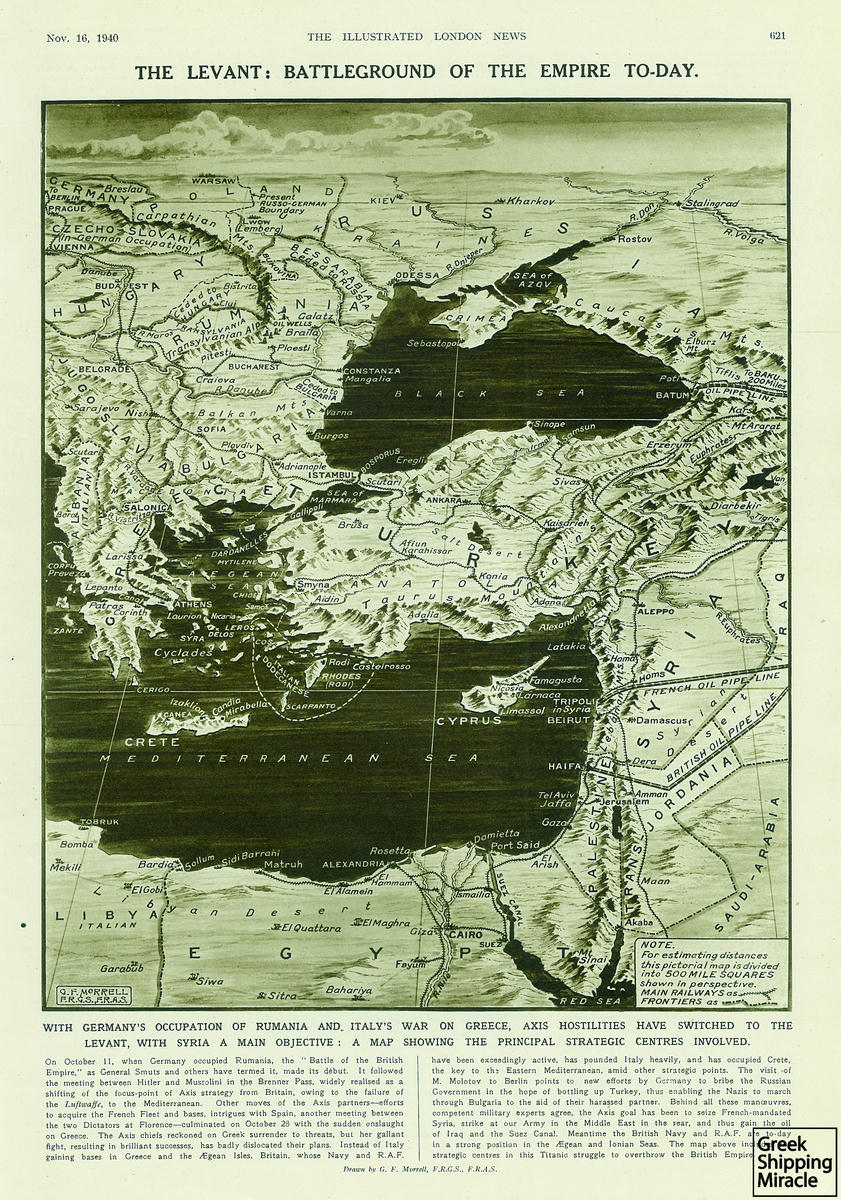

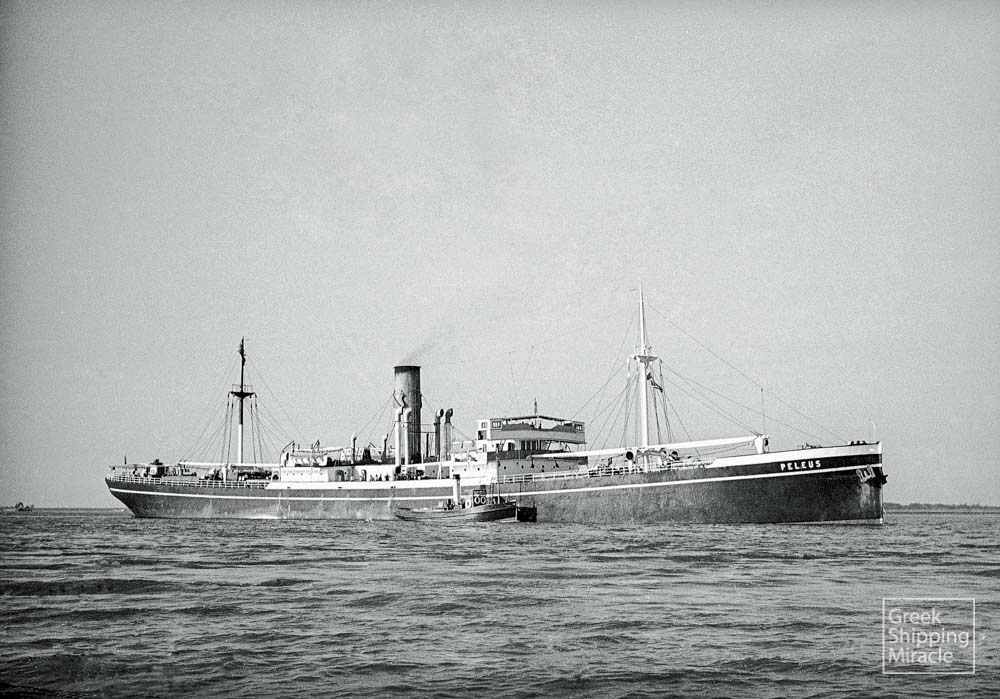

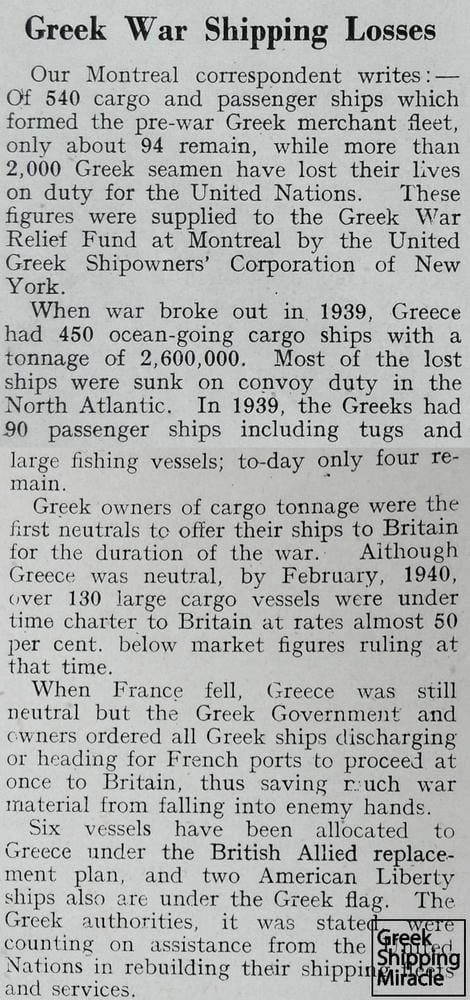

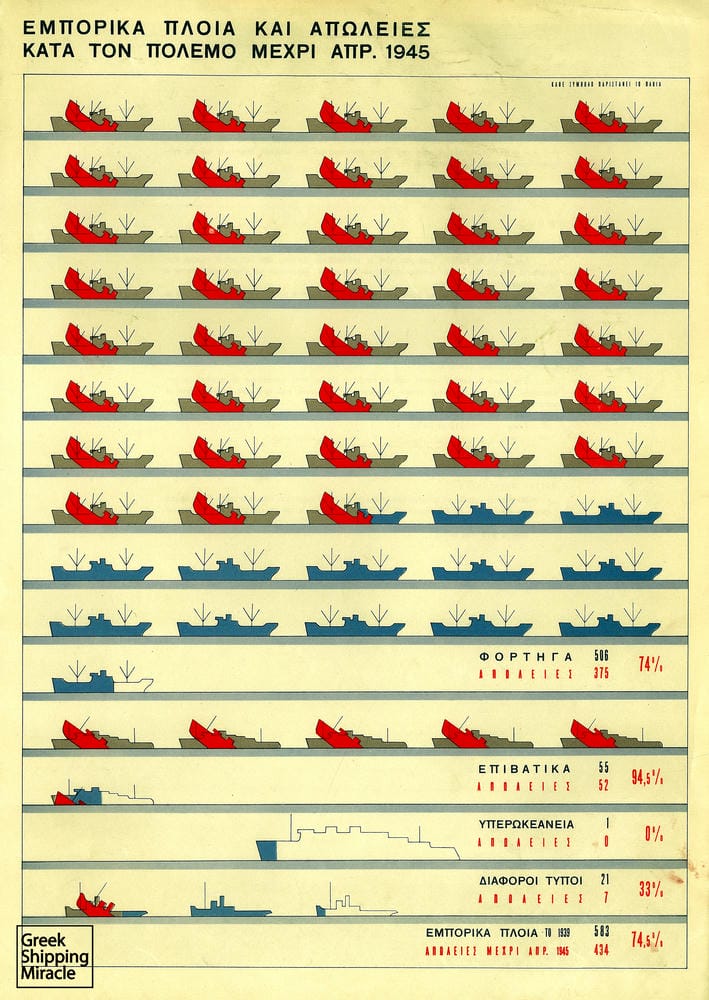

Despite Greece’s neutral stance during the first year of the war, the informal engagement of Greek shipping was evident ever since the declaration of the war in September 1939. This resulted in the loss of about 90 Greek steamers due to acts of war, even before Greece gave its resounding answer to Mussolini’s ultimatum.

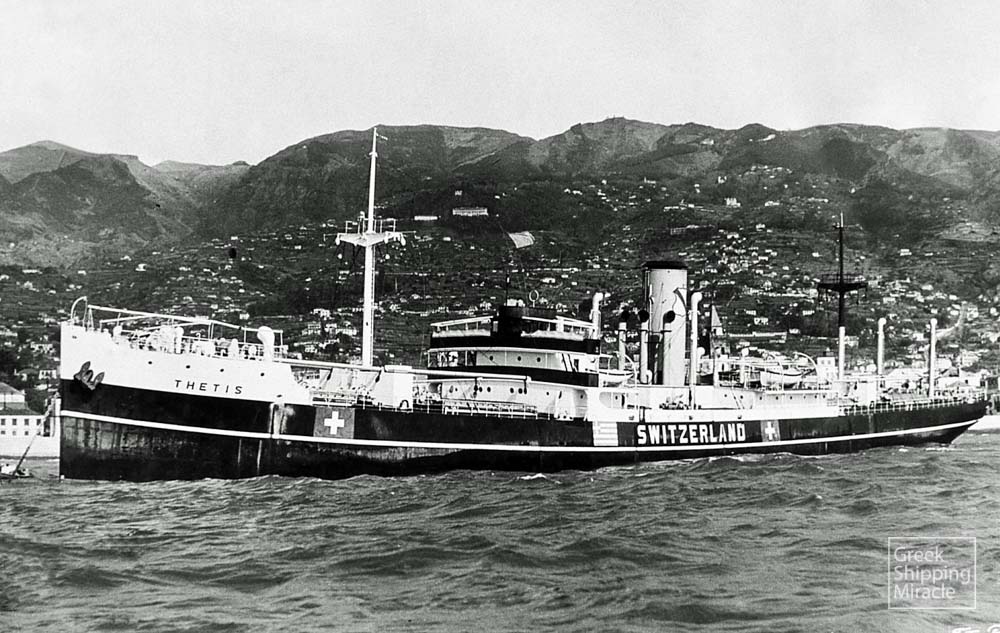

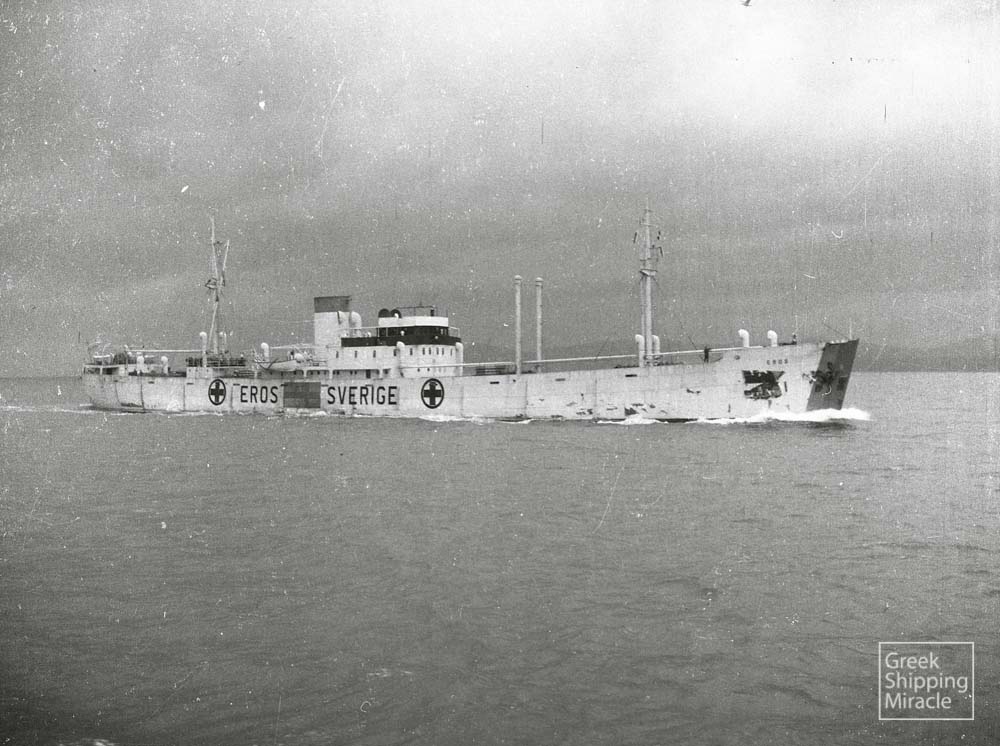

With the exception of 15 cargo ships chartered to the Swiss government before the outbreak of the War, the entire Greek merchant fleet fought and transported goods alongside the Allied Forces throughout the War. Its contribution to the successful outcome of the crucial Battle of the Atlantic was decisive.

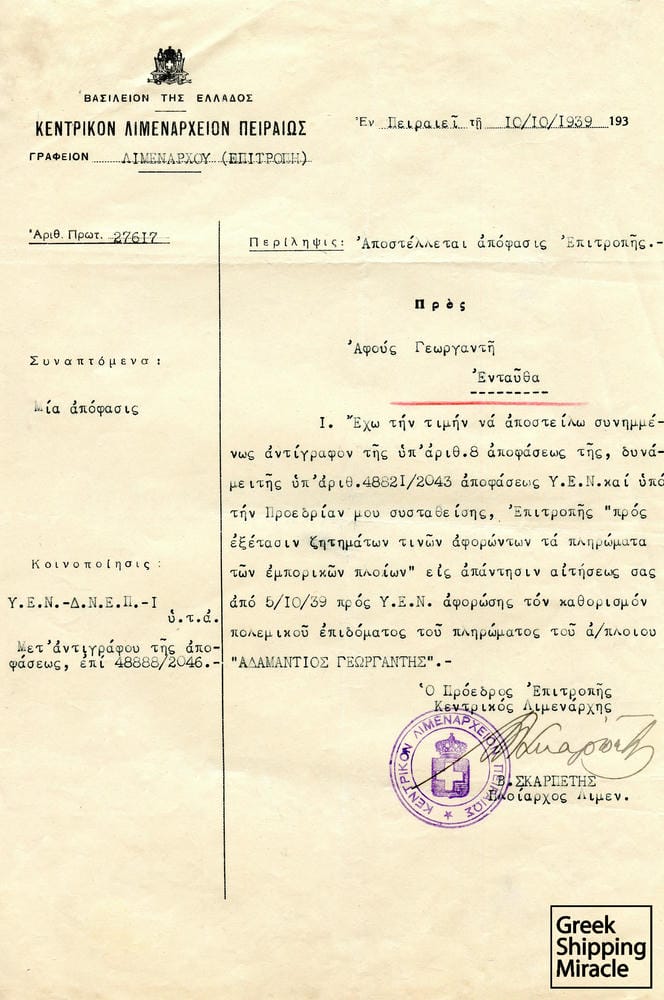

Back in Greece, the Metaxas government tried to adopt measures to manage the situation. The sale of ships to foreign interests was prohibited while penalties for rioters among seafarers were imposed. The government also introduced an emergency tax on profits and on the overvaluation of cargo vessels. At the same time, the Wartime Risk Insurance Agency was established, making the coverage against risk for ships’ crews mandatory.

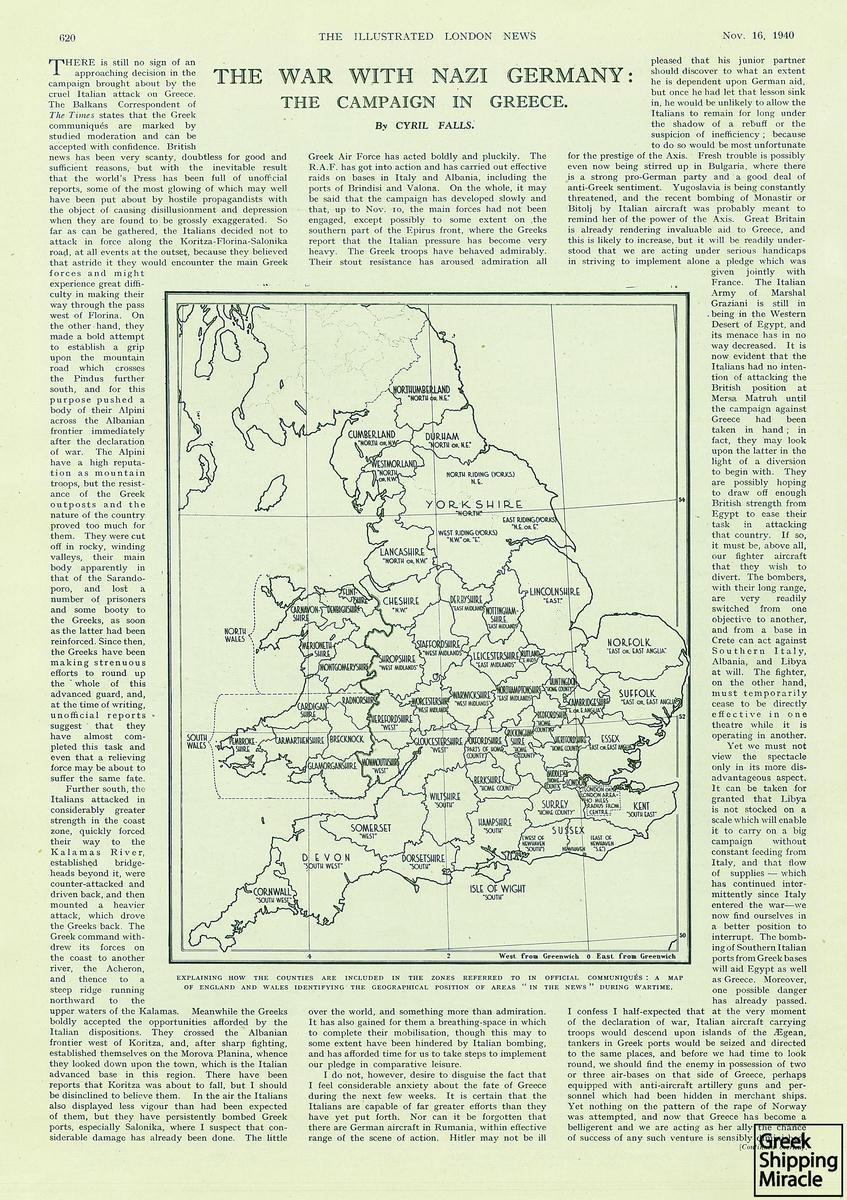

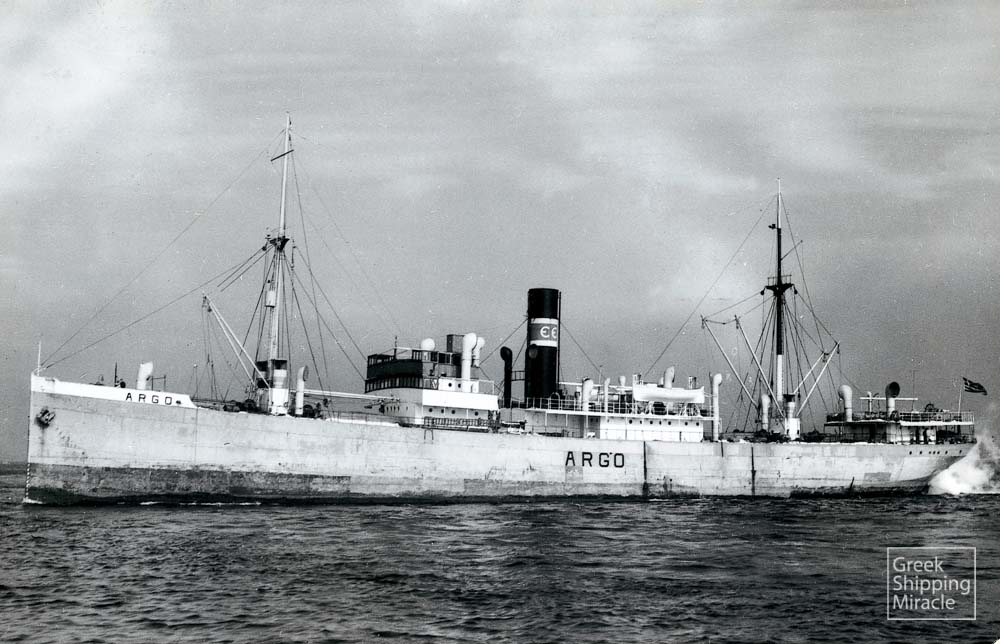

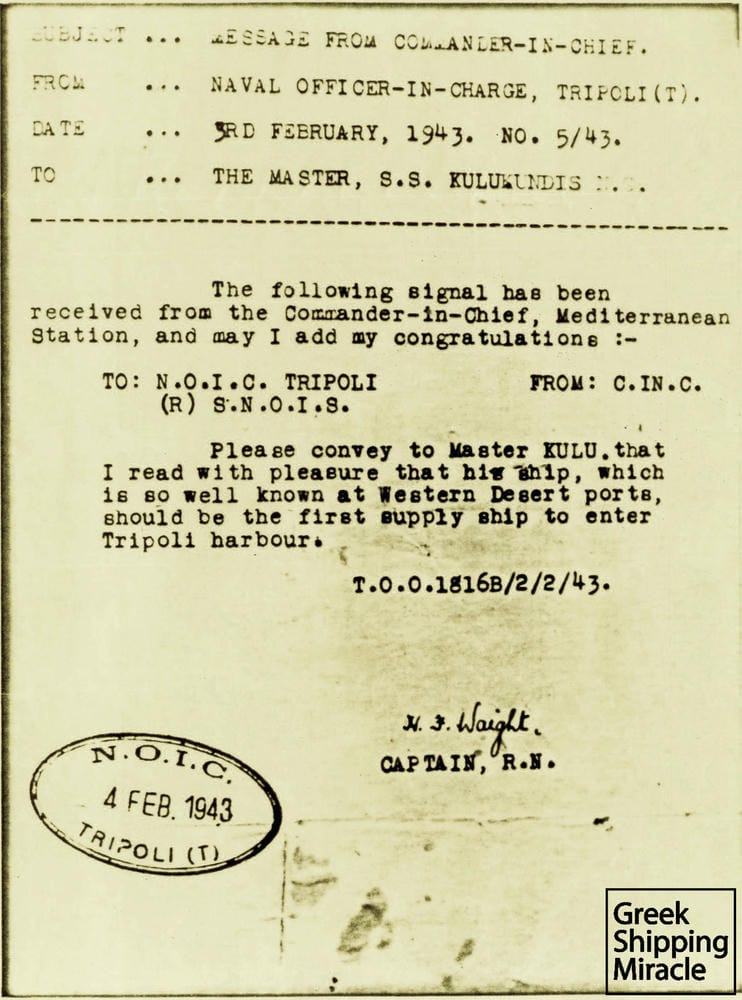

By the end of 1939, the Greek-flagged fleet numbered about 500 vessels, while about 100 additional Greek-owned steamships were sailing under British and Panamanian flags. With the outbreak of WWII, the British authorities attempted to charter a large number of Greek steamers. The offer was extremely low, and, despite the pressure exerted by having the advantage of controlling the insurance and bunker markets, it was categorically rejected by Manuel Kulukundis, who was leading the negotiations. In addition to the above, the Greek ambassador in London, Charalambos Simopoulos, expressed his strong objection to such a proposal, as it bore the risk of exposing the neutral status of Greece, and consequently avoided the chartering of almost half the Greek merchant fleet. Greek ships continued operating in a fast-rising free market until April 1940 when a deal was eventually reached, under which 150 vessels were chartered to the British over a period of six months.

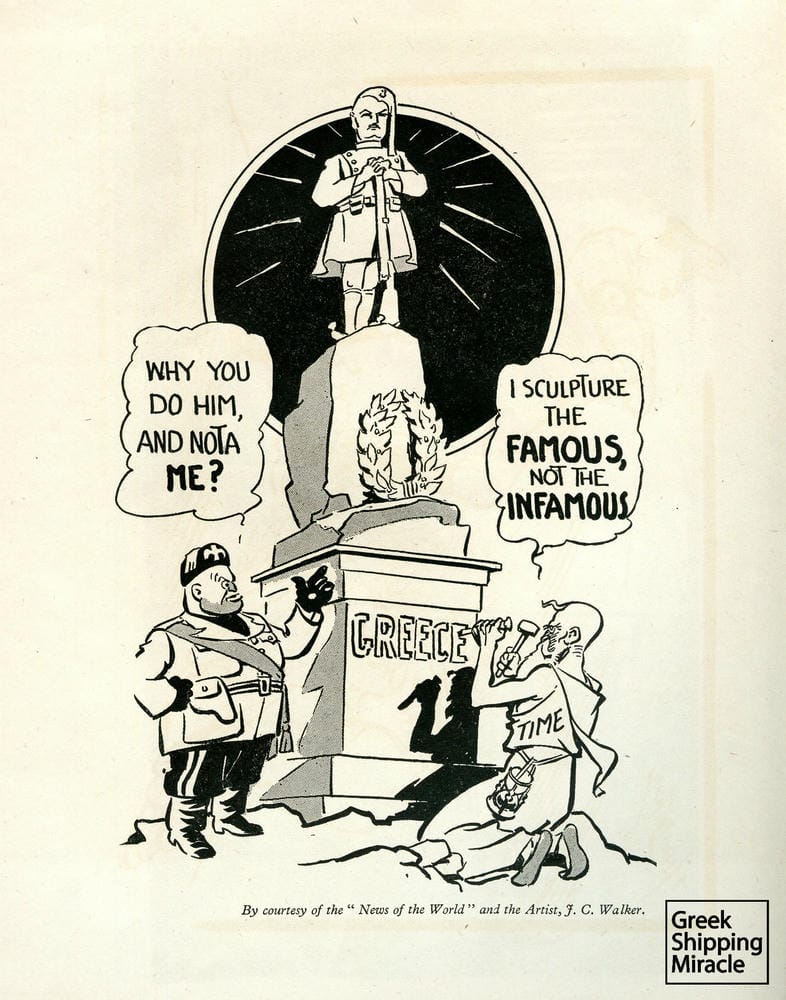

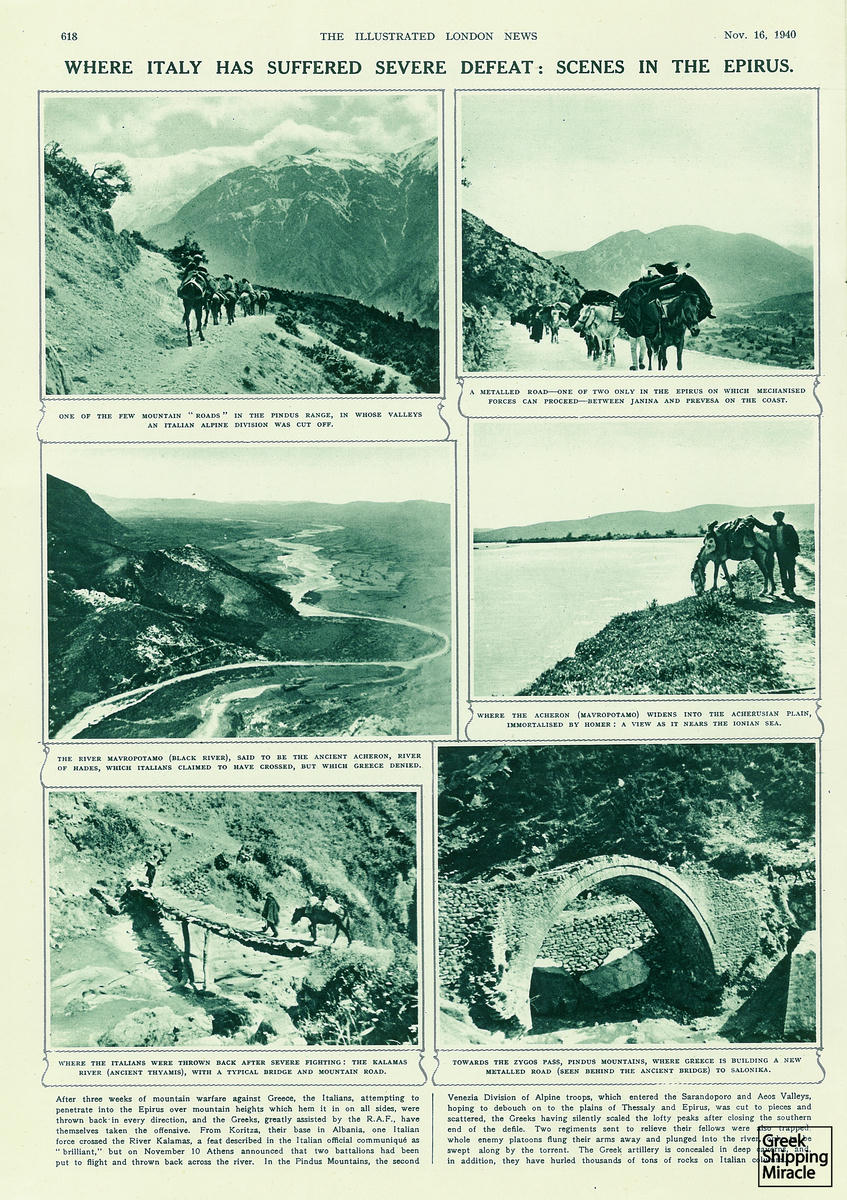

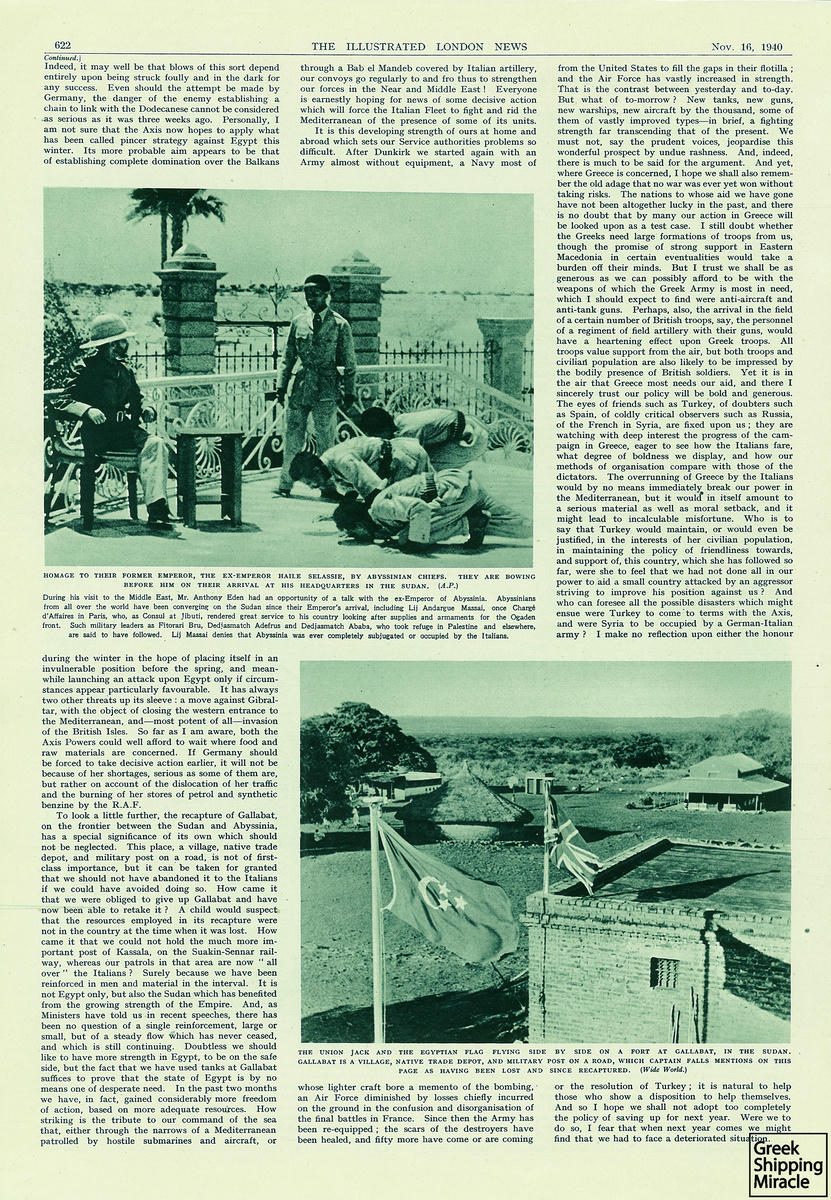

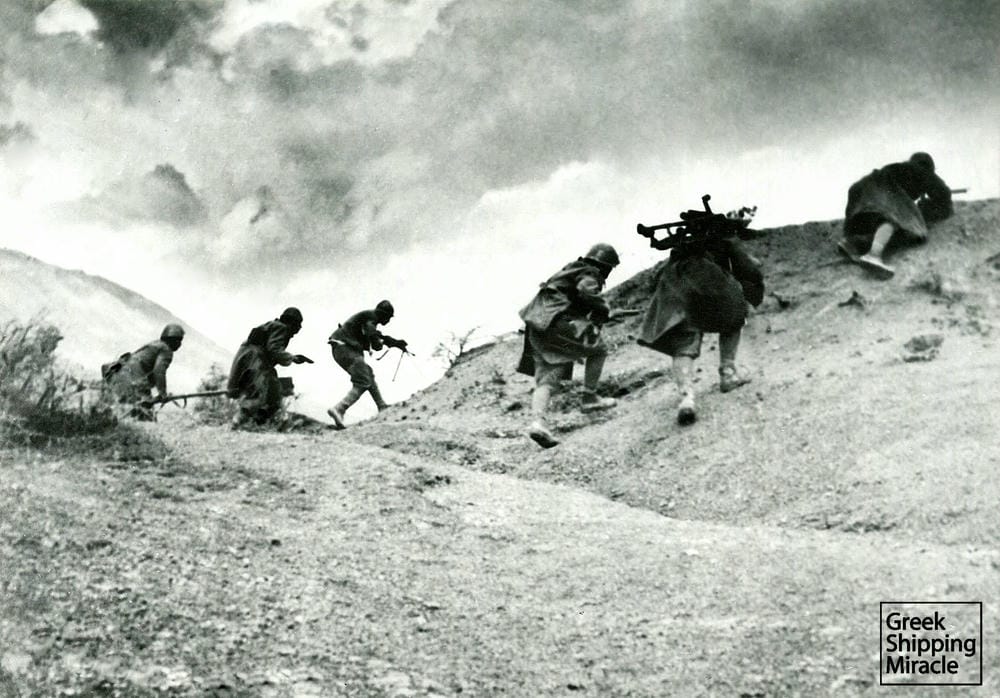

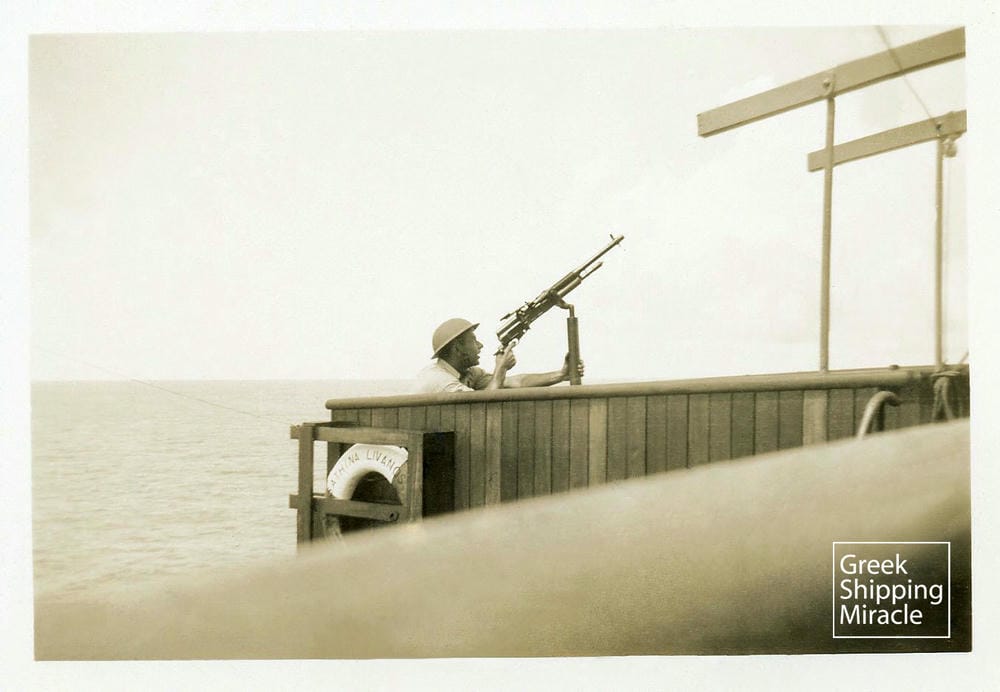

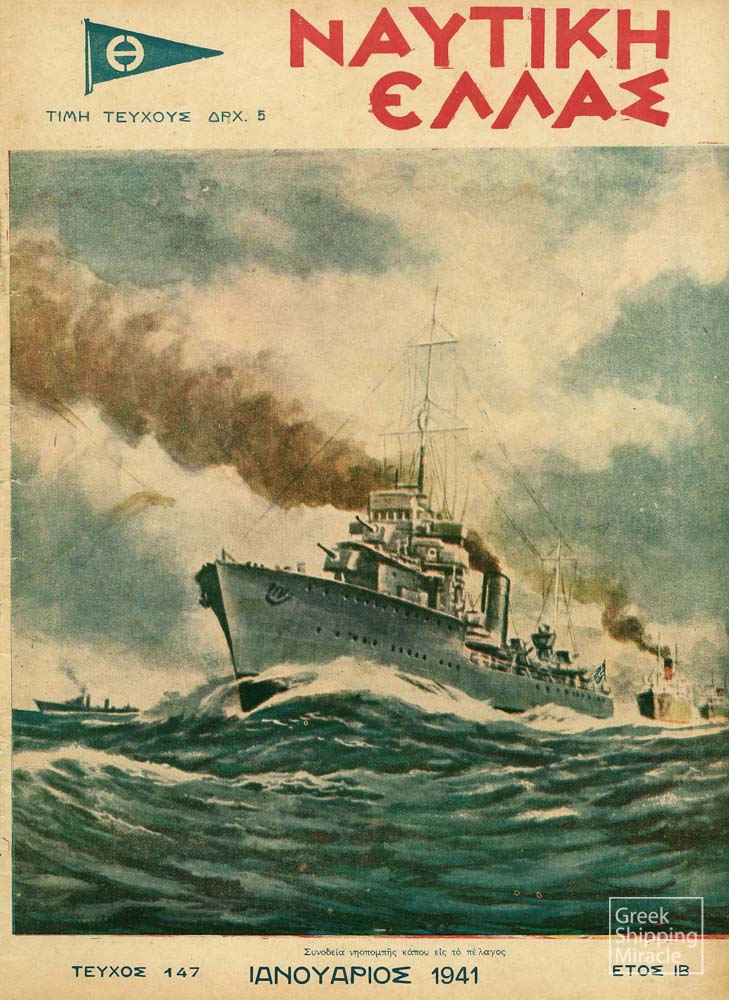

The Italian attack against Greece on 28 October 1940 marked the entry of Greece into WWII. Greek cargo ships played a crucial role transporting about 4/5 of supplies and troops bravely fighting on the Albanian front. At the same time, Greek merchant ships, apart from the service offered operating alongside the Allied forces, continued serving the country’s supply requirements.

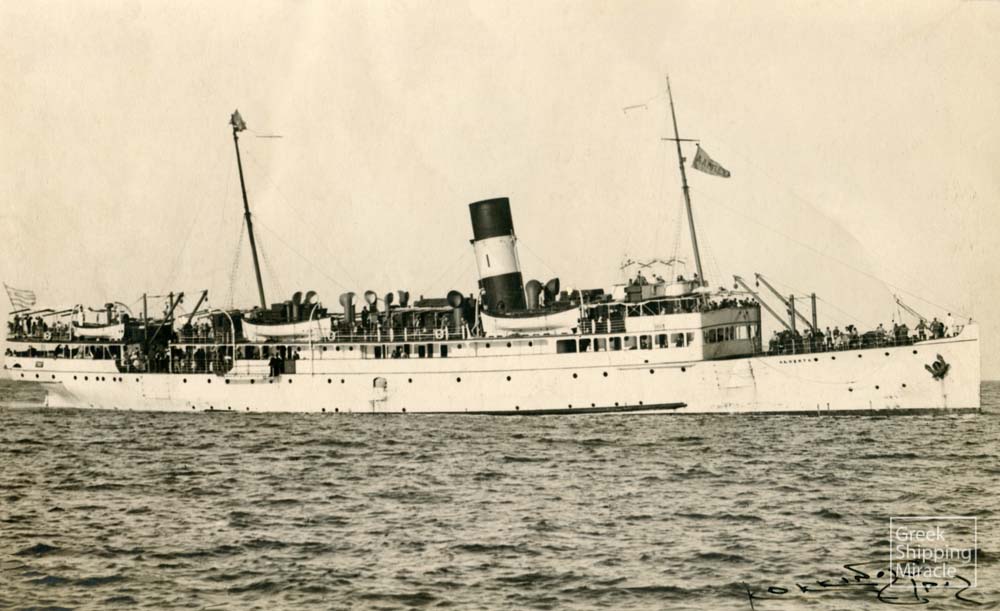

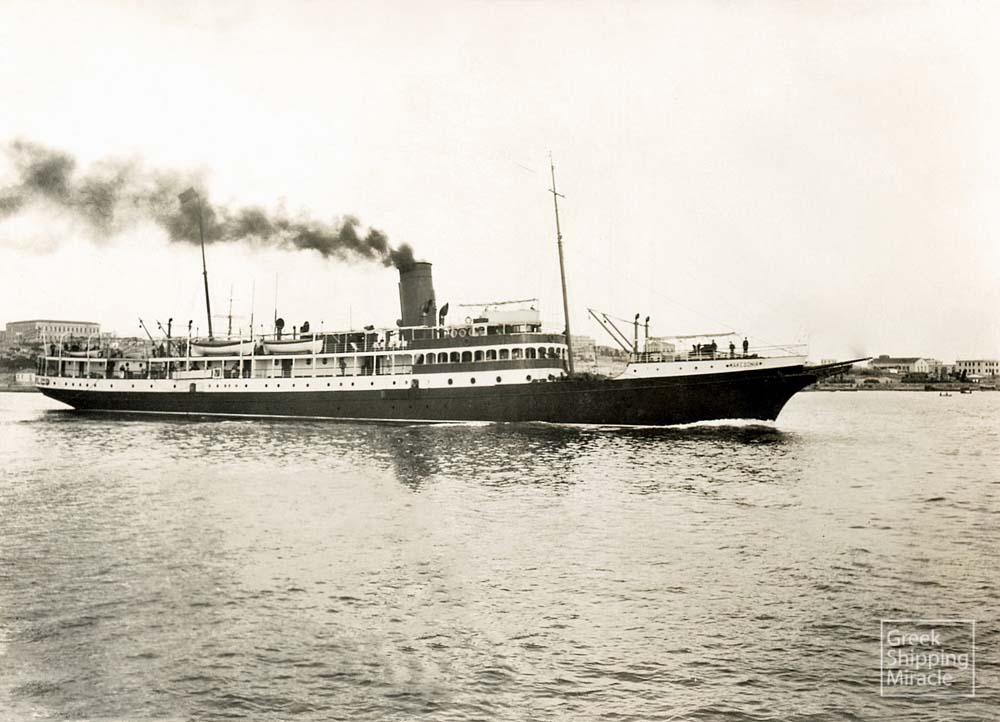

Following the Italian defeat, Germany had no alternative but to occupy Greece with its own forces. On 6 April 1941, the Germans invaded the country from the Greek-Bulgarian borders and due to the power of their air force managed to move further south. Following successive air strikes, almost 120 Greek vessels, including the entire passenger fleet and five hospital ships were hit and sunk in Greek waters. Only four passenger vessels managed to survive escaping to the Middle East.

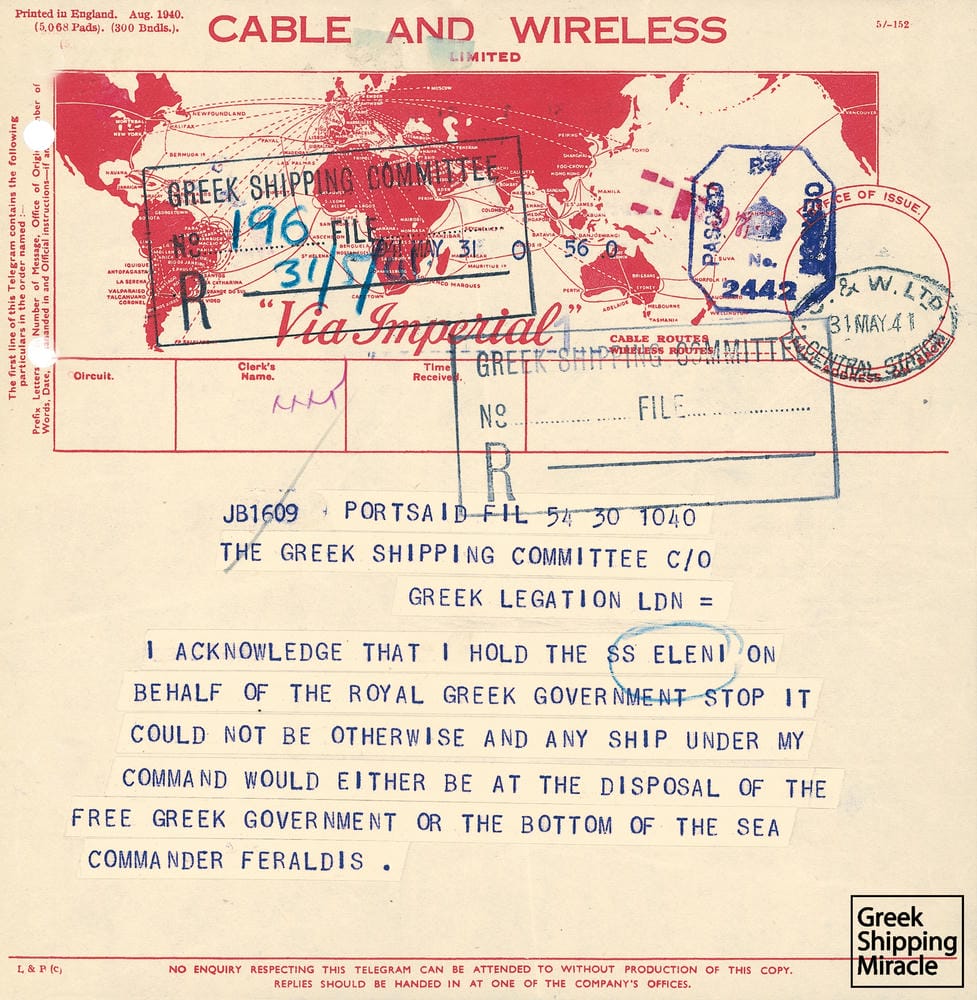

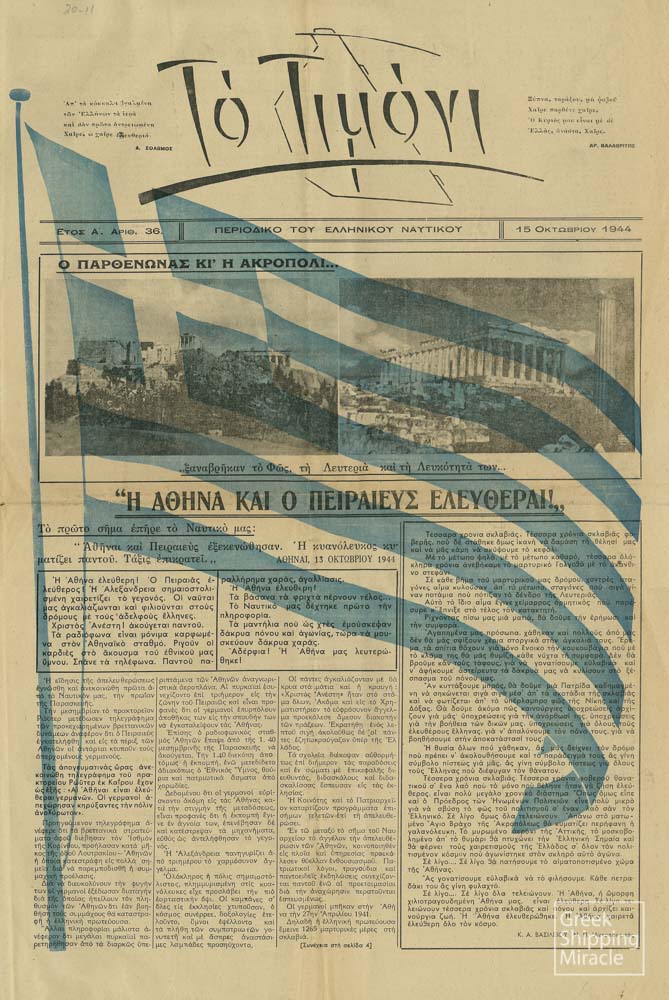

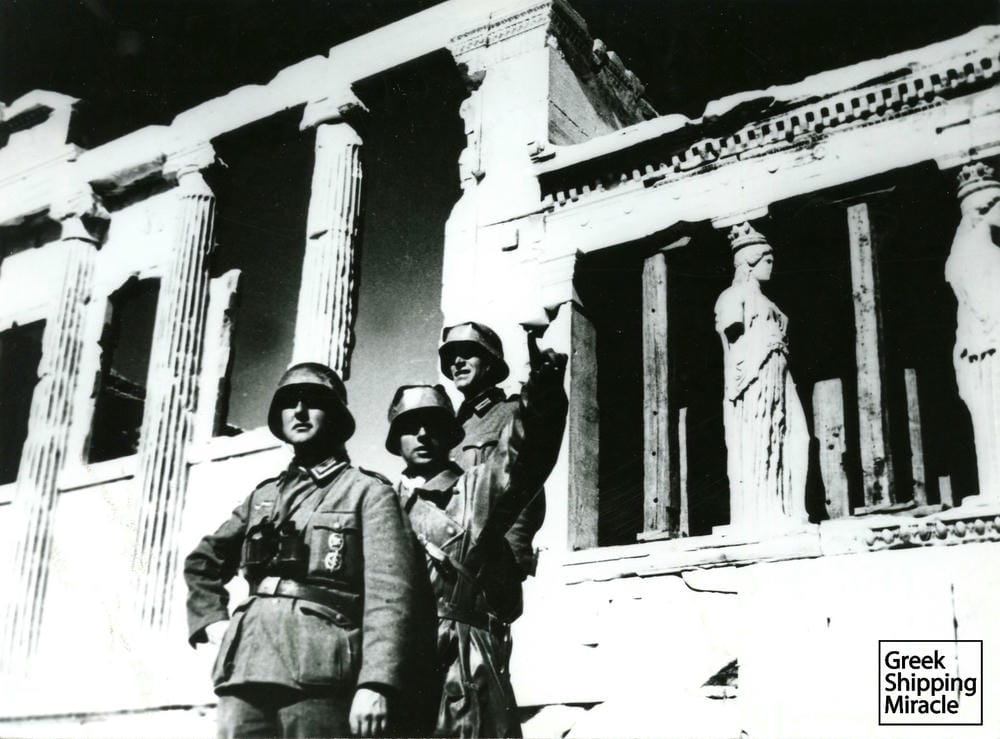

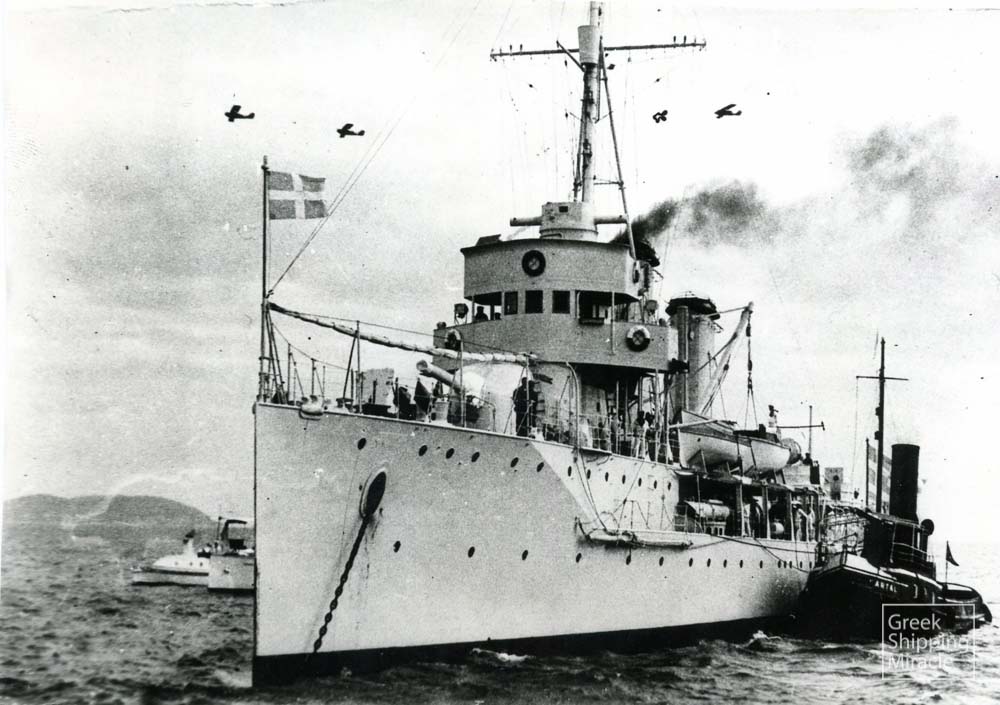

On 27 April 1941, the German swastika was raised on the Acropolis, the symbol of Athens, formalising the occupation of the Axis powers in Greece. However, no matter how the country’s conquerors tried, they never succeeded in imposing the total lowering of the Greek flag. The Greek seafarers did not allow at any point any other flag but the Greek to be raised on Greek registered vessels, the latter being official Greek territory.

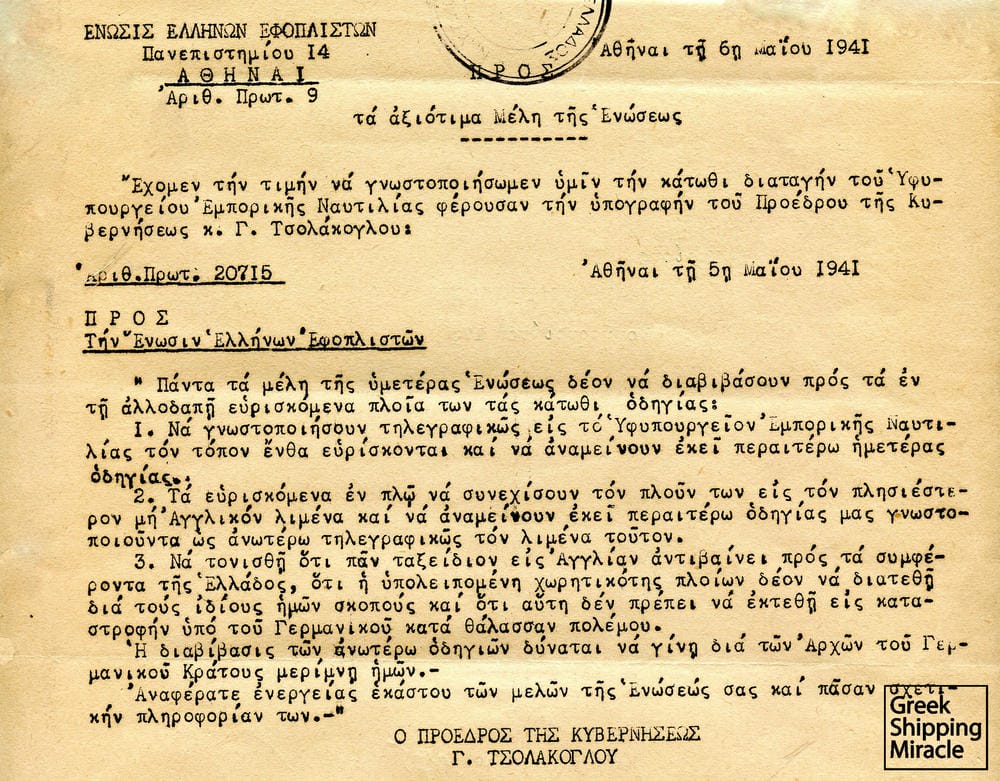

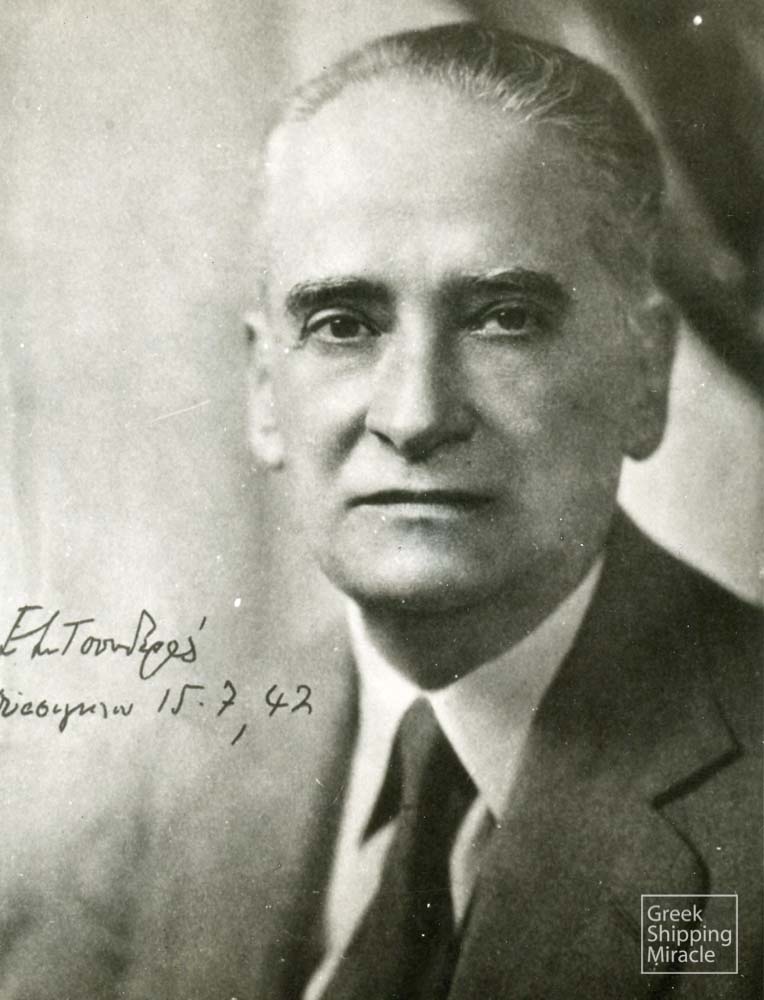

Among Germany’s first priorities following the occupation of Athens was to secure the control of Greek cargo steamers still in service outside the Greek borders. The Prime Minister of the puppet government Georgios Tsolakoglou dispatched a letter to the Union of Greek Shipowners on 5 May 1941, requesting all its members to convey to their ships the orders, according to which all vessels would be placed at the disposal of German forces. However, a few days before the occupation of Athens, the Union of Greek Shipowners’ legal advisor, Georgios Daniolos had taken the initiative to burn all relative files that could link the ownership of ships with individuals in order to prevent the transfer of ownership of the vessels.

This action did not stop the Germans who were eager to control the Greek fleet. Employing another tactic, they offered to acquire Greek ships with official memorandums of agreements, stating that under British control they were useless to the Greeks anyway. The offer was tempting as most shipowners would have been able to support themselves with the funds. However, when they realised that by doing this the Germans would be able to demand delivery of all Greek ships calling in neutral ports, they pretended they were only managers and that the real owners were based abroad. The Germans continued to press and threaten with imprisonment in order to achieve their purpose, but failed to break the owners’ resolve. The conqueror’s plan to take control of the Greek merchant fleet was permanently shelved.

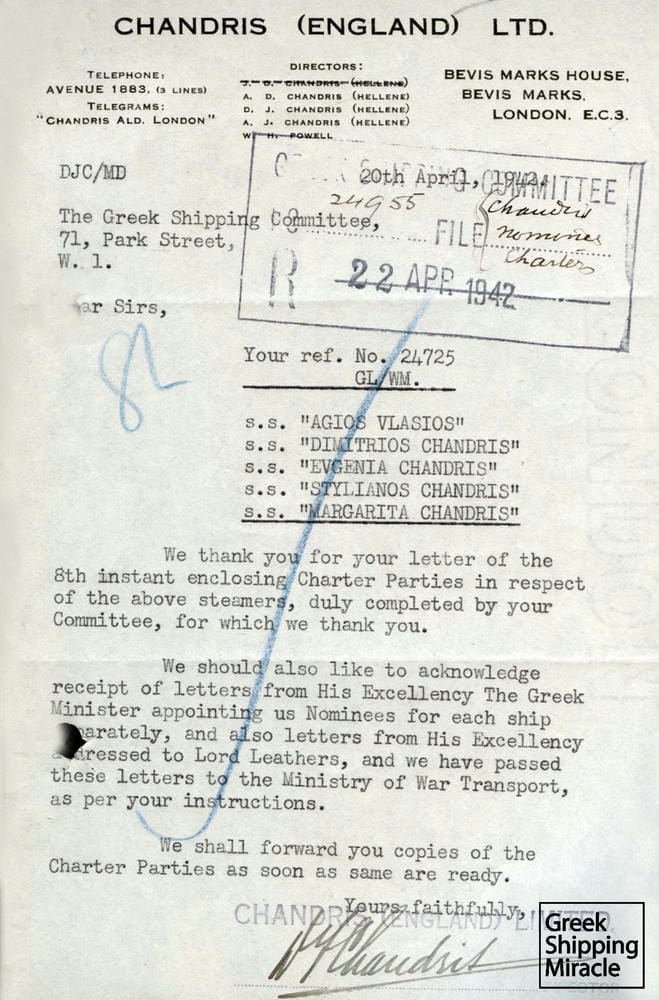

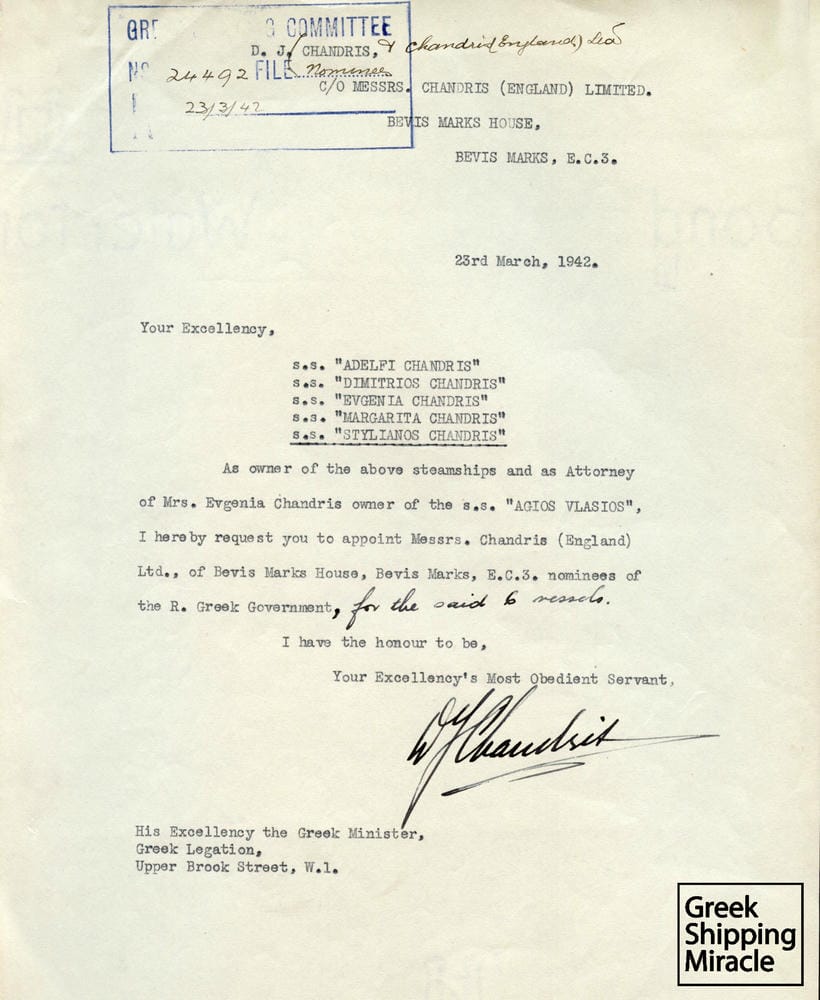

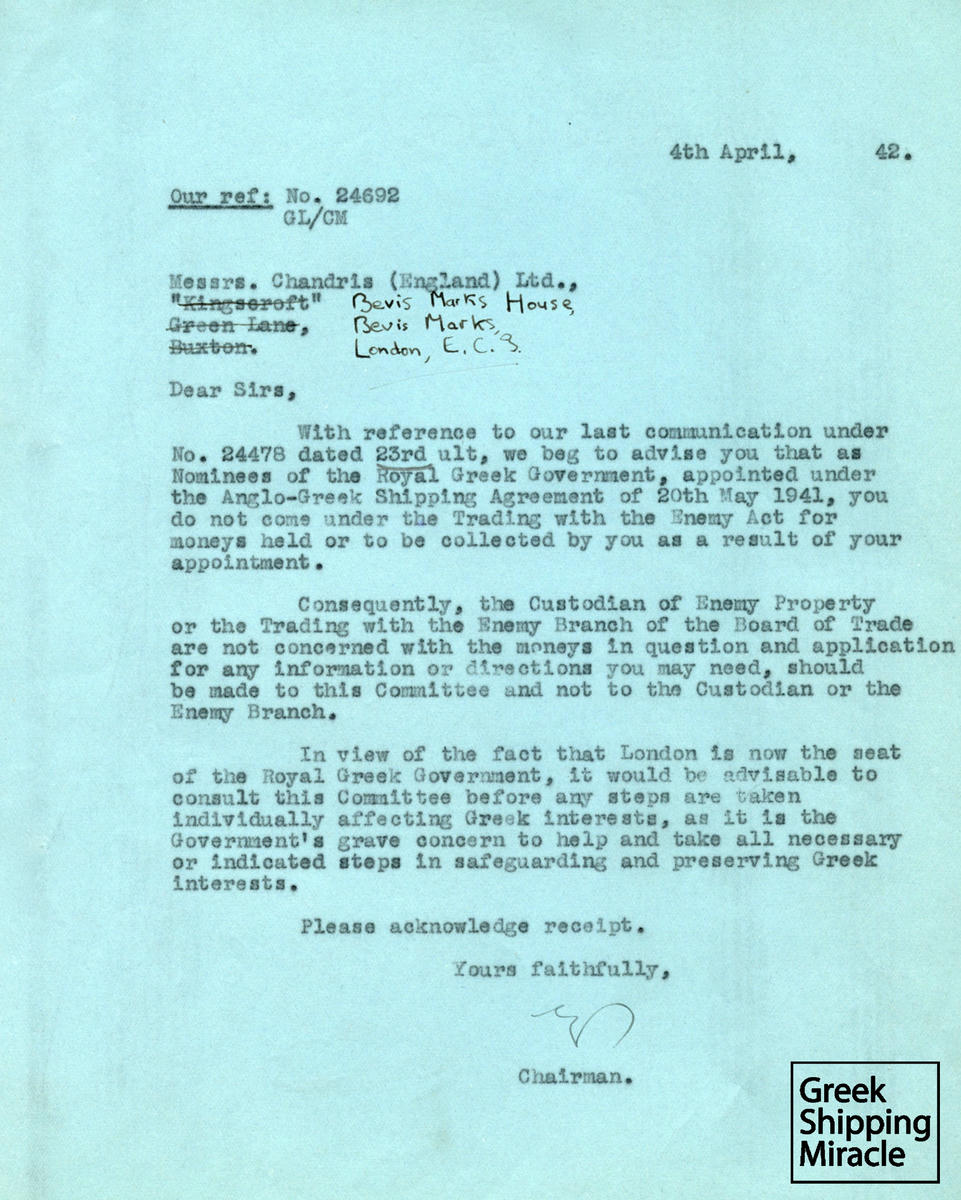

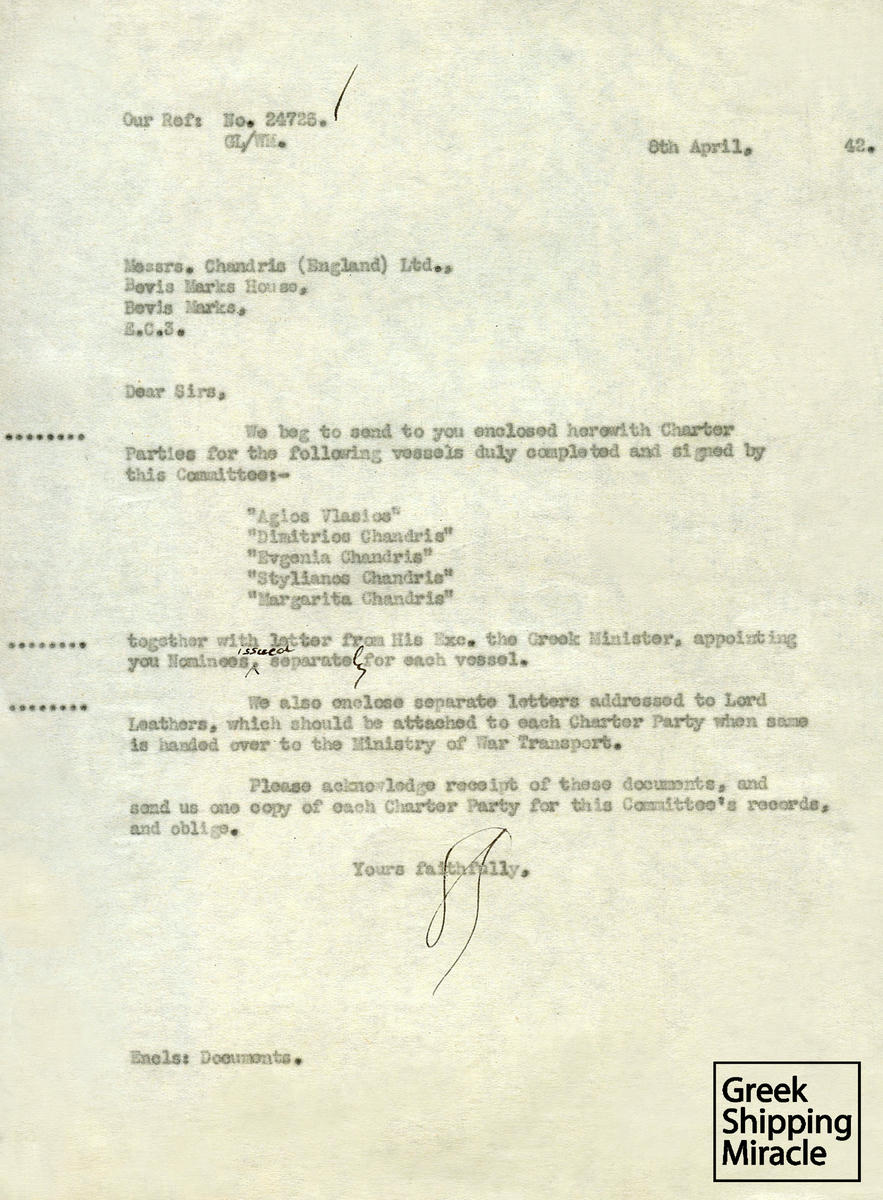

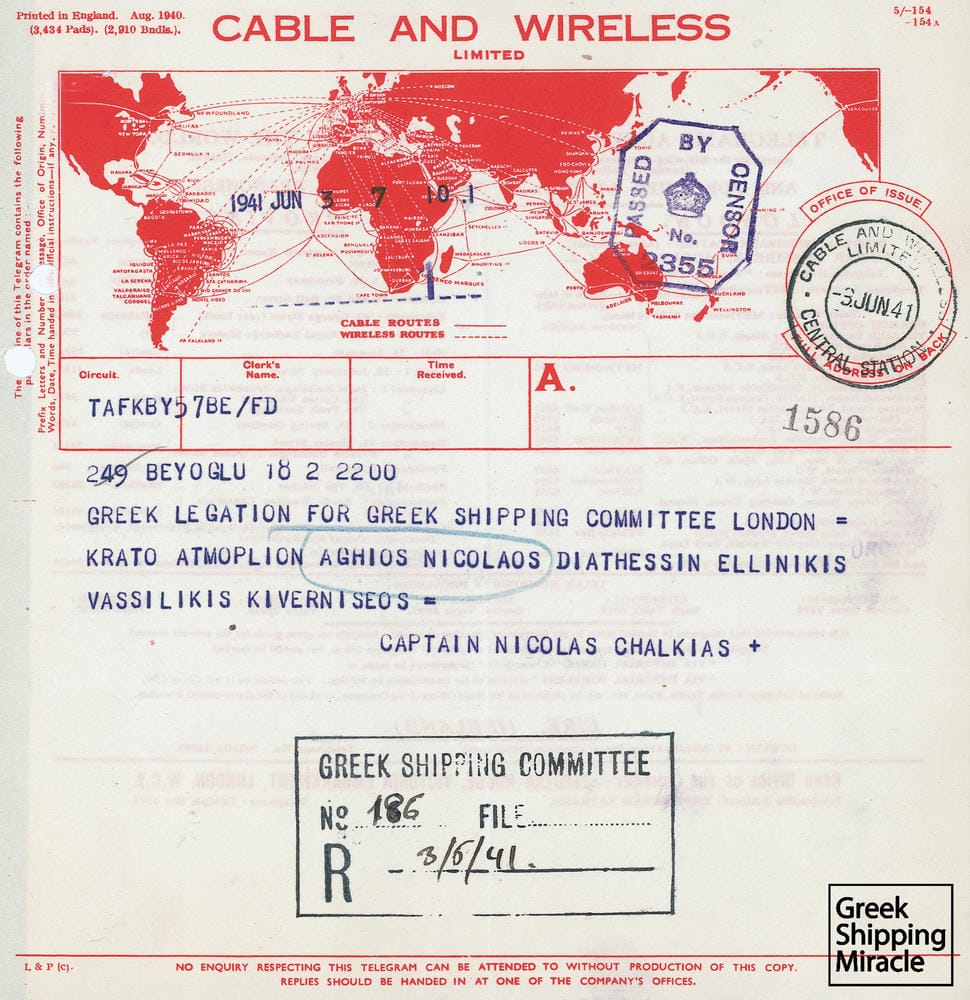

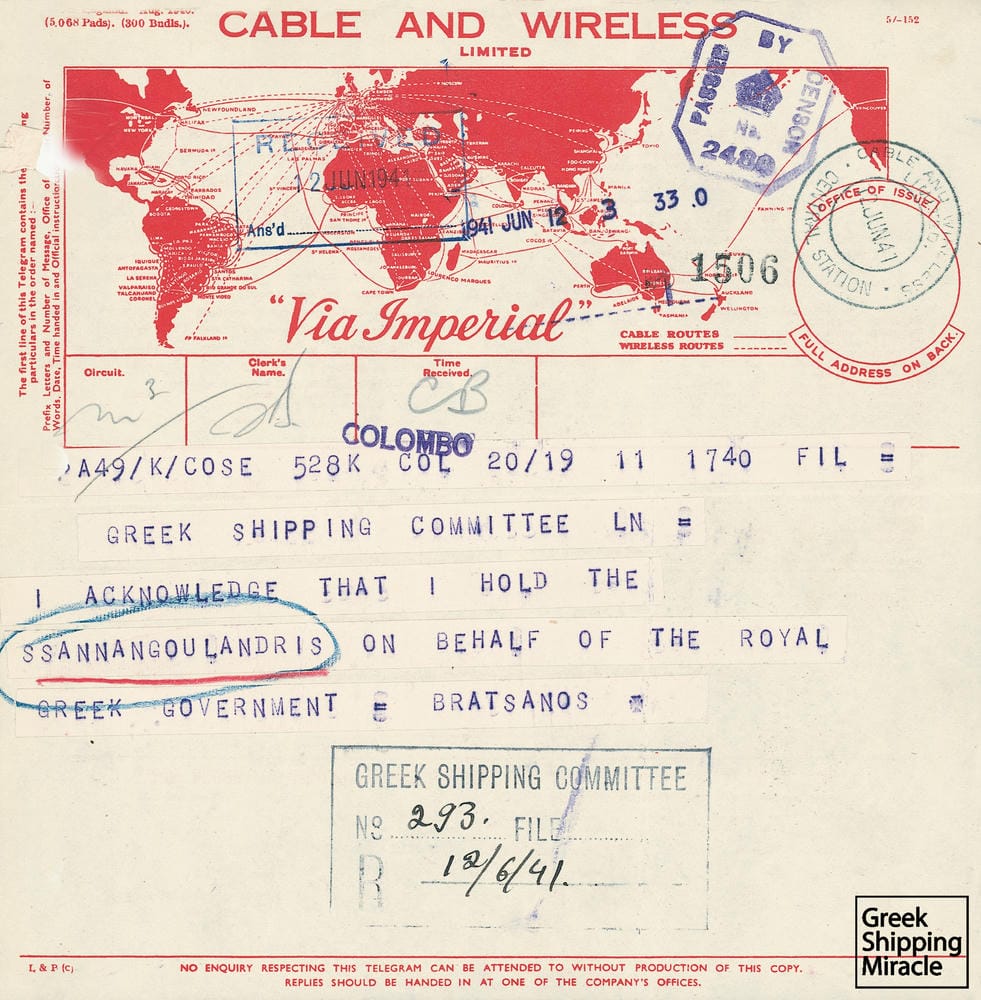

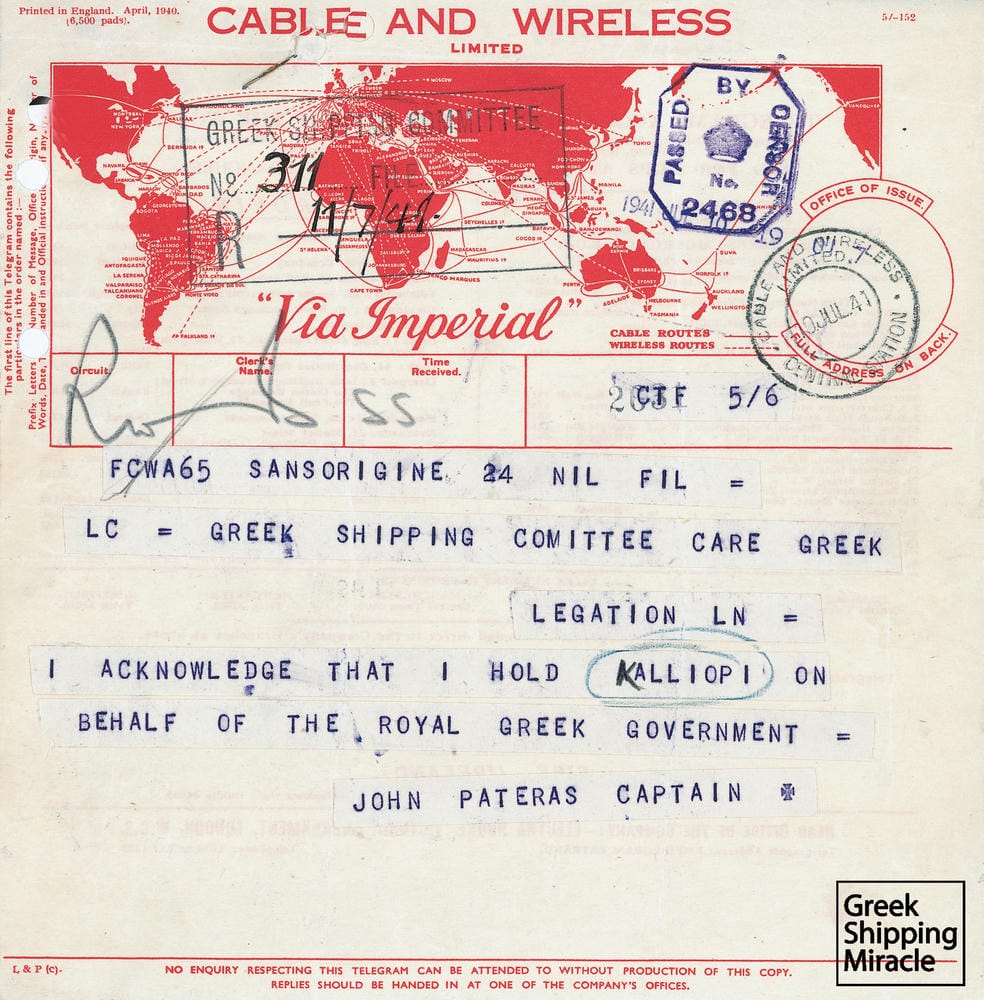

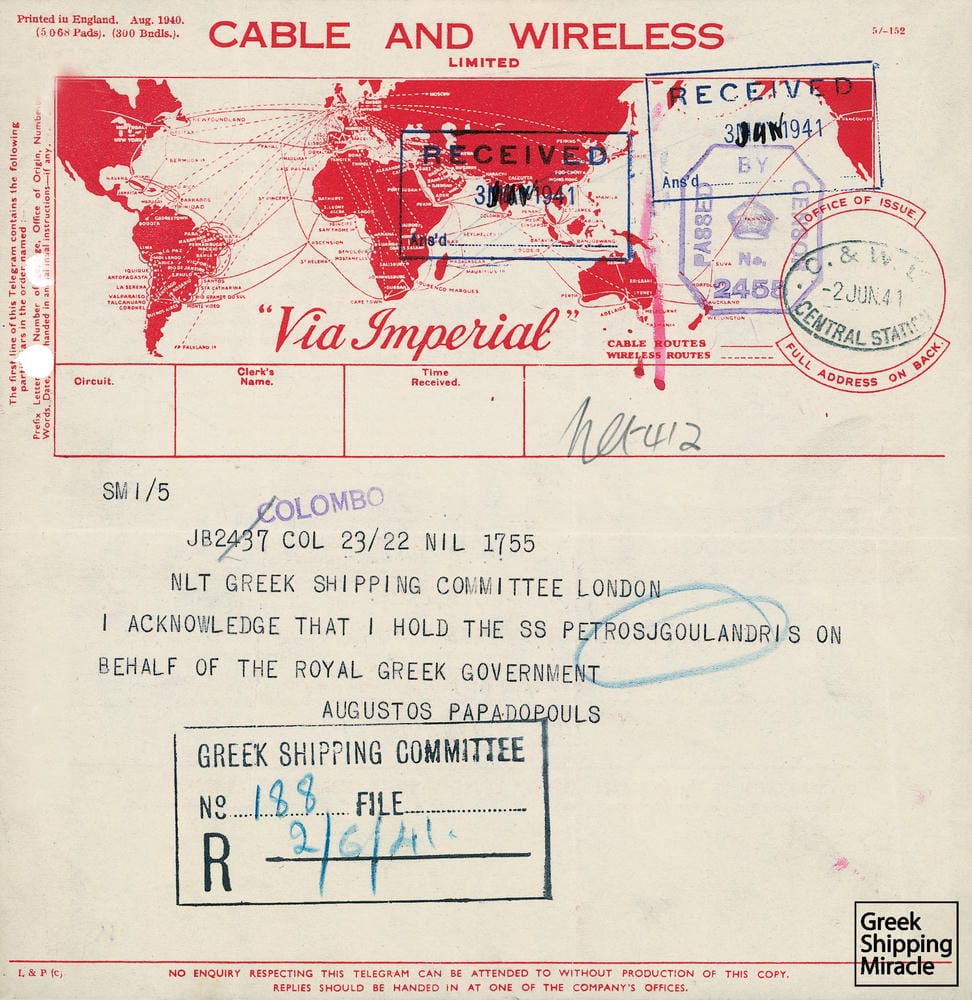

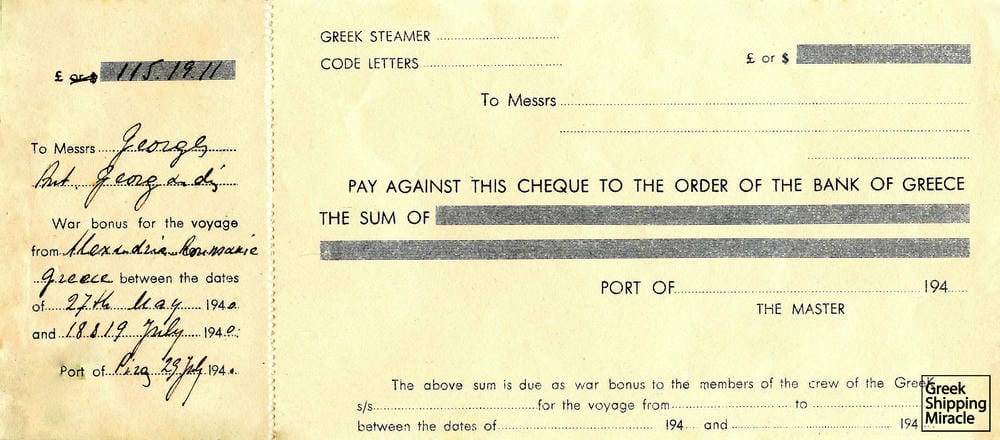

Meanwhile, the remaining Greek ships were requisitioned by order of the official government of Greece, headed by Emmanuel Tsouderos. Formed under tragic circumstances with the support of the British when the German forces were approaching Athens, the government had eventually moved to Crete. Following the requisition order, all ships were placed under the control of the British forces throughout the War plus an additional six-month period after its termination, according to the Anglo-Hellenic Agreement signed by the government. This agreement was made in the absence of shipowners, depriving them of securing more favourable terms. Thus, the Greek merchant fleet, despite offering invaluable services to the Allies by carrying a total of 40 million tons of supplies, and suffering the tragic loss of over 2,000 Greek seafarers as well as the decimation of about 70% of the fleet’s pre-war capacity, was left devastated after the War with its owners lacking the necessary funds for its reconstruction. It must be stated that throughout the War, shipowners acted as managers of their own ships, appointed by the Greek Maritime Commission that was set up in London under the control of the Greek ambassador. Their income was restricted to a monthly hire, equal for all ships and basically covering operating costs, which were unfortunately constantly rising. This was due to excessive demands by seafarers, whose requests were readily met by the Greek government, residing at that time in Cairo.

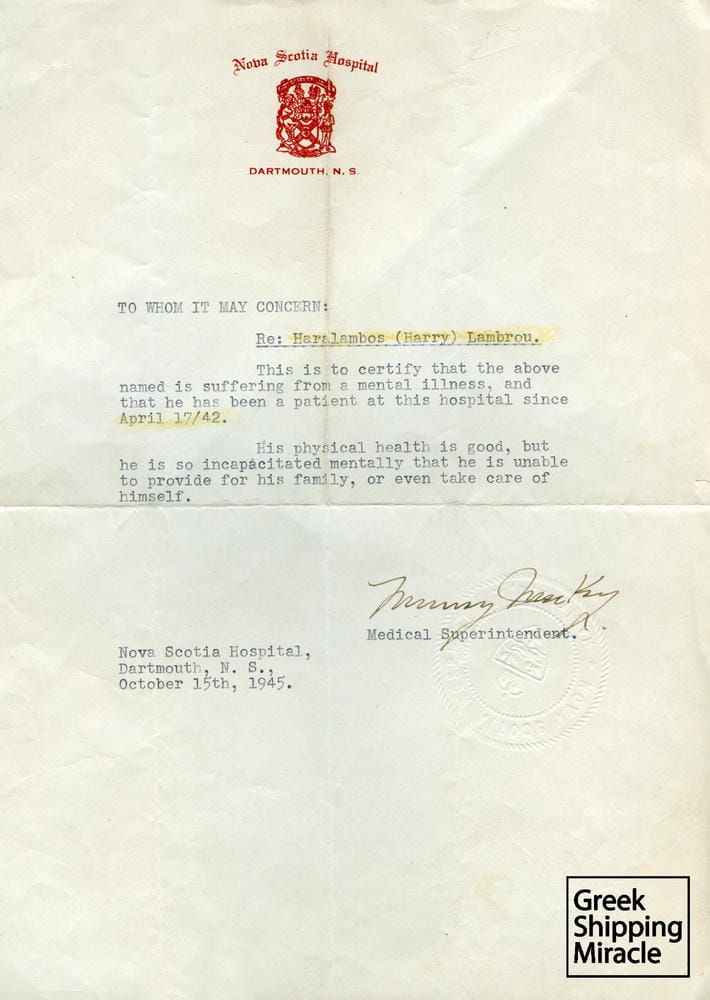

Unfortunately, the epic performance of Greek shipping during the War was marked by several problems created among seafarers following the fall of Greece in April 1941. Under these conditions, many Greek sailors were driven to the United Kingdom and especially to Cardiff where the Panhellenic Seamen’s Federation (PNO) first set up offices followed two years later by the communist-controlled Organization of Greek Seamen’s Union (OENO). The latter, with the support of local leftist unions and under the tolerance of the Greek government in Cairo, managed to take control of the situation onboard many Greek ships and put forward its views to many seafarers who were physically and mentally exhausted by tragic conditions created by the War. Ships were constantly torpedoed at the time, while seafarers were concerned about the fate of their families and relatives in Greece, since they were practically unable to arrange for money to be sent to them. At the same time, the government in exile was not able to address these serious issues at hand. This situation led many seafarers to desperation, disturbing the order onboard the ships and even reaching the state of mutiny in a few cases. Despite the fact that the entire Greek seafaring family demonstrated heroism and self-sacrifice throughout the War, such behaviour and excessive demands by seafarers led to unpleasant results. By the end of WWII, Greek-flagged ships had lost their competitive status, as their operating expenses were less only compared to those of the US-flag fleet. On the other hand, the state of harmonious co-operation between owners and seafarers, which had served as the cornerstone for the evolution of Greek shipping, was seriously shaken.

At the end of the War, the Greek-flagged fleet had been reduced to a mere 150 ships, less than those that had survived WWI. The task of reconstruction was now even harder because of the Greek government’s agreement to charter the entire fleet to the British authorities at a relatively low hire. This had deprived the industry of sufficient funds to rebuild the fleet in post-war years.

Thus, the only significant financial compensation from the enormous sacrifice of the Greek fleet was some 12,000,000 pounds transferred to the Greek government in Cairo, constituting surplus money from the chartering of the Greek fleet. These funds were used to cover the costs of the government’s operation during the War and were thus never returned to the Greek shipowners.

On the other side of the coin, despite the shipping industry’s economic losses, a significant development came to be in 1944. In acknowledgment of the invaluable contribution of the industry, the government had the status of the under-ministry of Merchant Marine upgraded to Ministry.