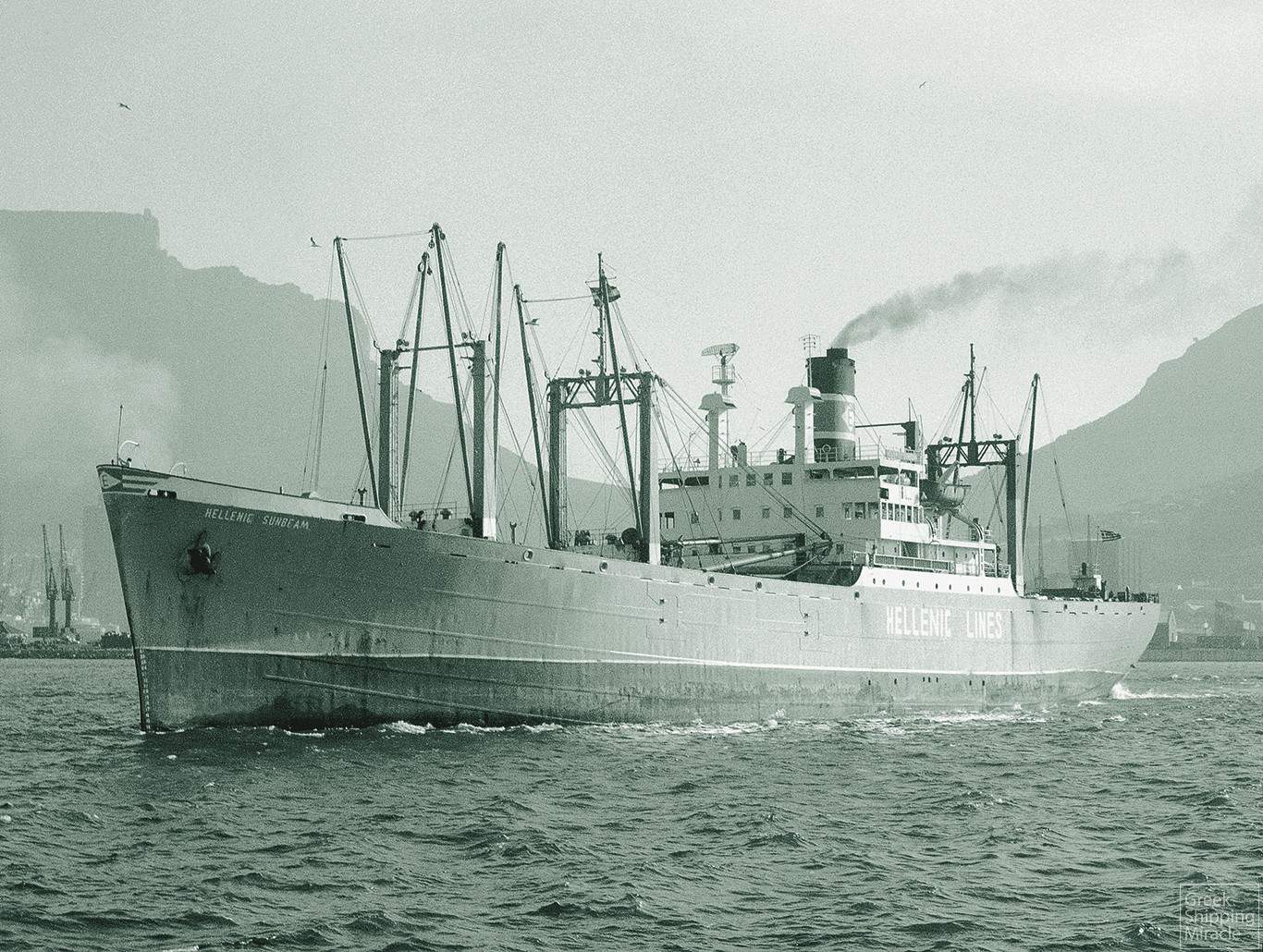

HELLENIC LINES

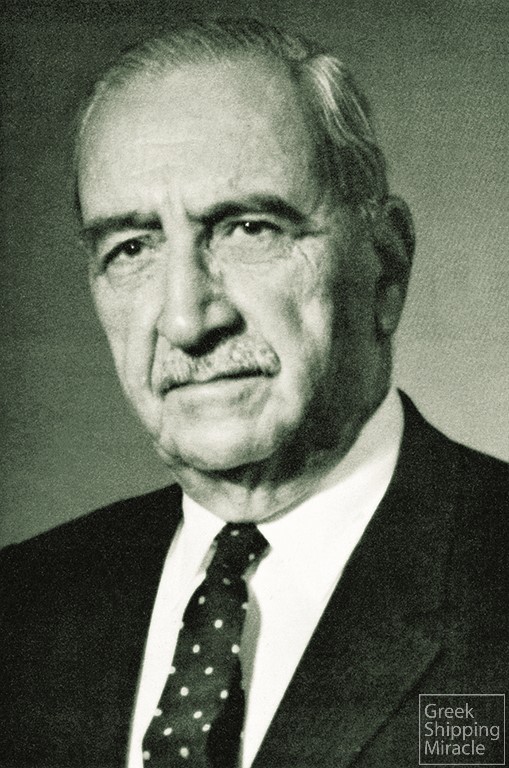

Hellenic Lines S.A. was established by Pericles G. Callimanopulos, a prominent figure in Greek shipping. He was one of the few Greek shipowners who ventured into the particularly demanding sector of liners at a time when every new “interloper”, especially one from the Southeastern Mediterranean, was met with a negative reaction by Northern Europe’s traditional big players. Thanks to a strong personality and unwavering commitment to his vision, he managed to go against the times, founding and heading Hellenic Lines, a group which, for over half a century, provided exemplary services to international maritime transport and, by extension, to the global economy. All of the ships of the Hellenic Lines fleet flew the Greek flag and were always manned by the finest Greek seafarers.

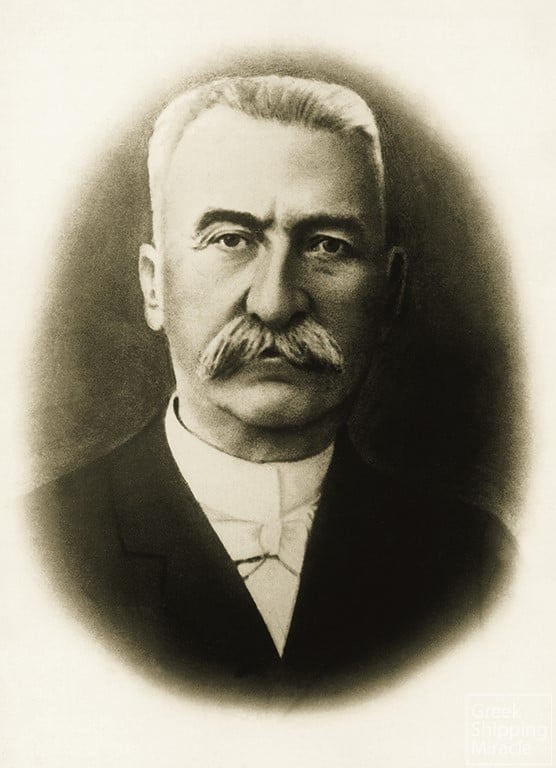

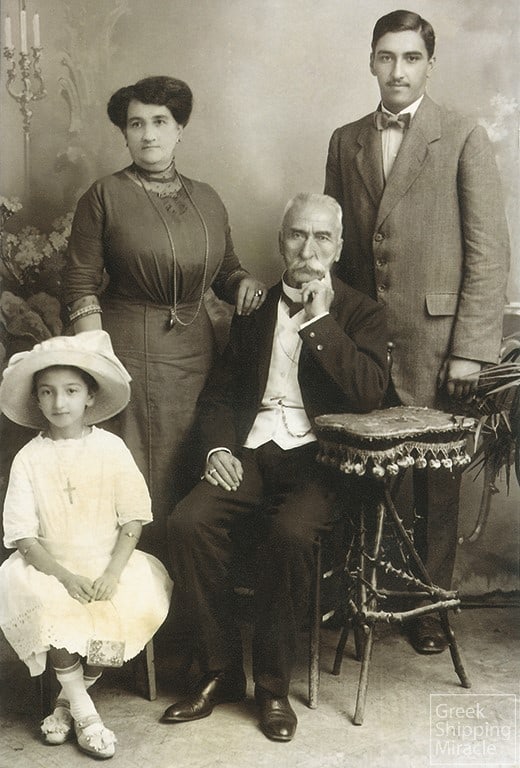

Born in Patras in 1892, he was one of five children of customs officer Gregory Callimanopulos – a grandson of chieftain Kallimanis, one of the leading figures of the 1821 revolution in Kalavryta, in the struggle for Greece’s idependence from Ottoman rule.

After graduating from the Patras Gymnasium and studying accounting, Pericles Callimanopulos, who was already fluent in three foreign languages – English, French and German – emigrated to Egypt at the age of 19. He worked there for a short time before returning to Piraeus where he was hired by the Koulis shipping agency, which represented liner companies. The agency also maintained offices in Egypt, the management of which was soon taken on by the young Callimanopulos.

His stay in Egypt was inevitably cut short by his recruitment during World War I. After the end of the war, he decided to pursue an independent career in shipping. At first, he worked as a freight broker but soon became an agent for foreign liner companies as well as a coal merchant with his own warehouses, barges and tugboats, dealing mainly in ship coaling.

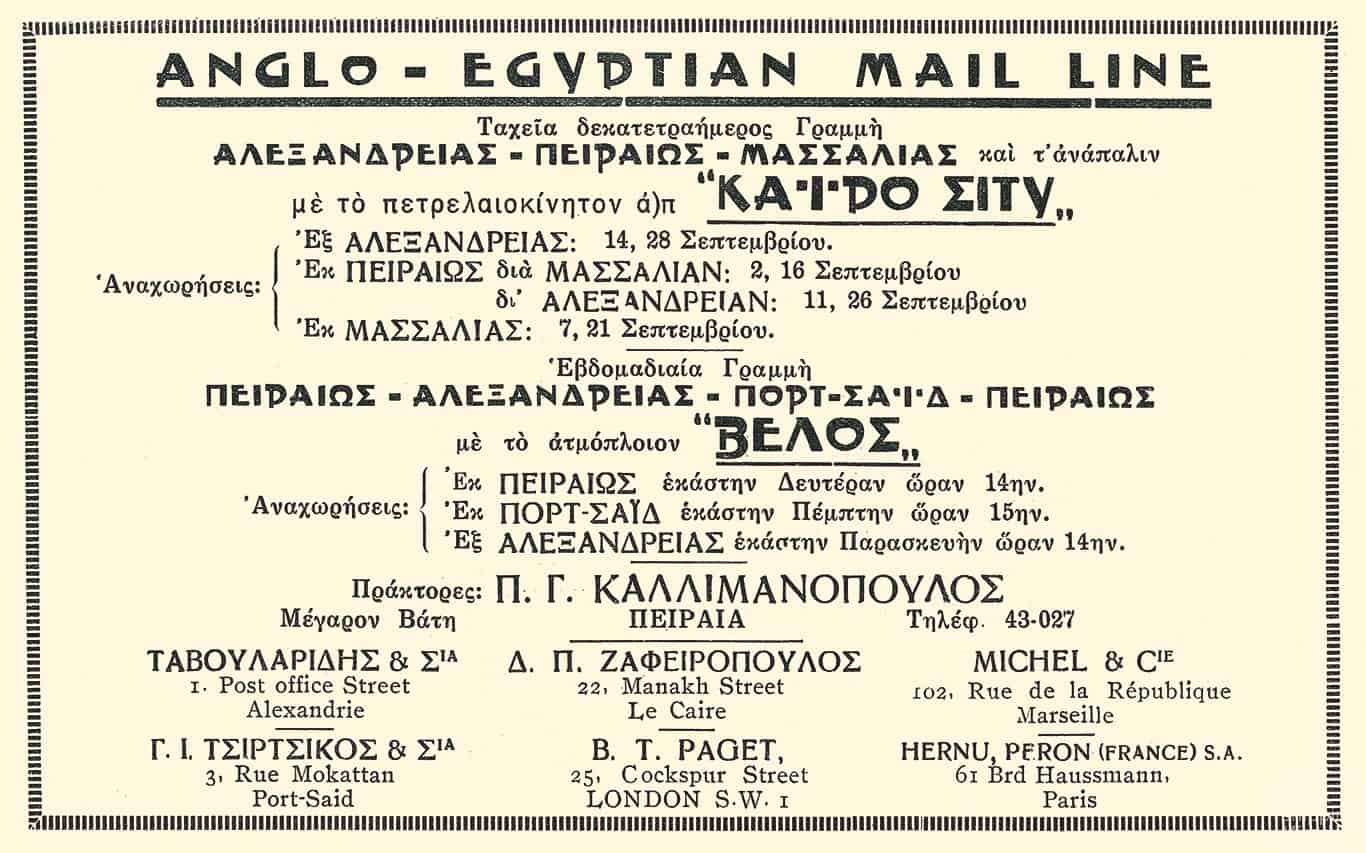

In 1924 Callimanopulos began his career as a shipowner with the acquisition of a 34-year-old steamer, renamed GRIGORIOS C. in honour of his father. This was followed by the purchase of another steamer, the EKATERINI C., in 1926. By the end of the 20s, he also acted as a third-party steamship manager. Among these steamers were two Greek-flagged British ships, which were auctioned by their owners’ creditors during the crisis that followed the 1929 Wall Street Crash and were eventually bought by their manager, Pericles Callimanopulos. One of them, after undergoing necessary repairs and renovation work, was renamed CAIRO CITY, remained under the British flag and came under the ownership of the Fenton Steamship Company Ltd., which was controlled by Callimanopulos and acted as a representative of Hellenic Lines in London in the post-war years. The CAIRO CITY served the Marseilles-Piraeus-Alexandria route known as the Anglo-Egyptian Mail Line and successfully travelled until the outbreak of World War II when it was requisitioned by the British Admiralty. After the end of the war, its owners received considerable compensation by the British government both for the use of the vessel and the damage it had suffered, while the ship itself – which never sailed again – was eventually sold for scrap in 1949. The same route was served by another British-flagged ship, the VELOS, starting in the mid-1930s.

In 1930, Pericles Callimanopulos married Anna Sismanoglou, with whom he had four children – three daughters and one son. Four years later, in 1934, the time had come for him to realise his dream of creating a liner company.

Callimanopulos had a very different mentality compared to all his fellow Greek shipowners. His experiences up until then had turned him more towards liner shipping, a sector in which he detected increased business stability vis-à-vis the dramatic reprecussions he observed in tramp shipping.

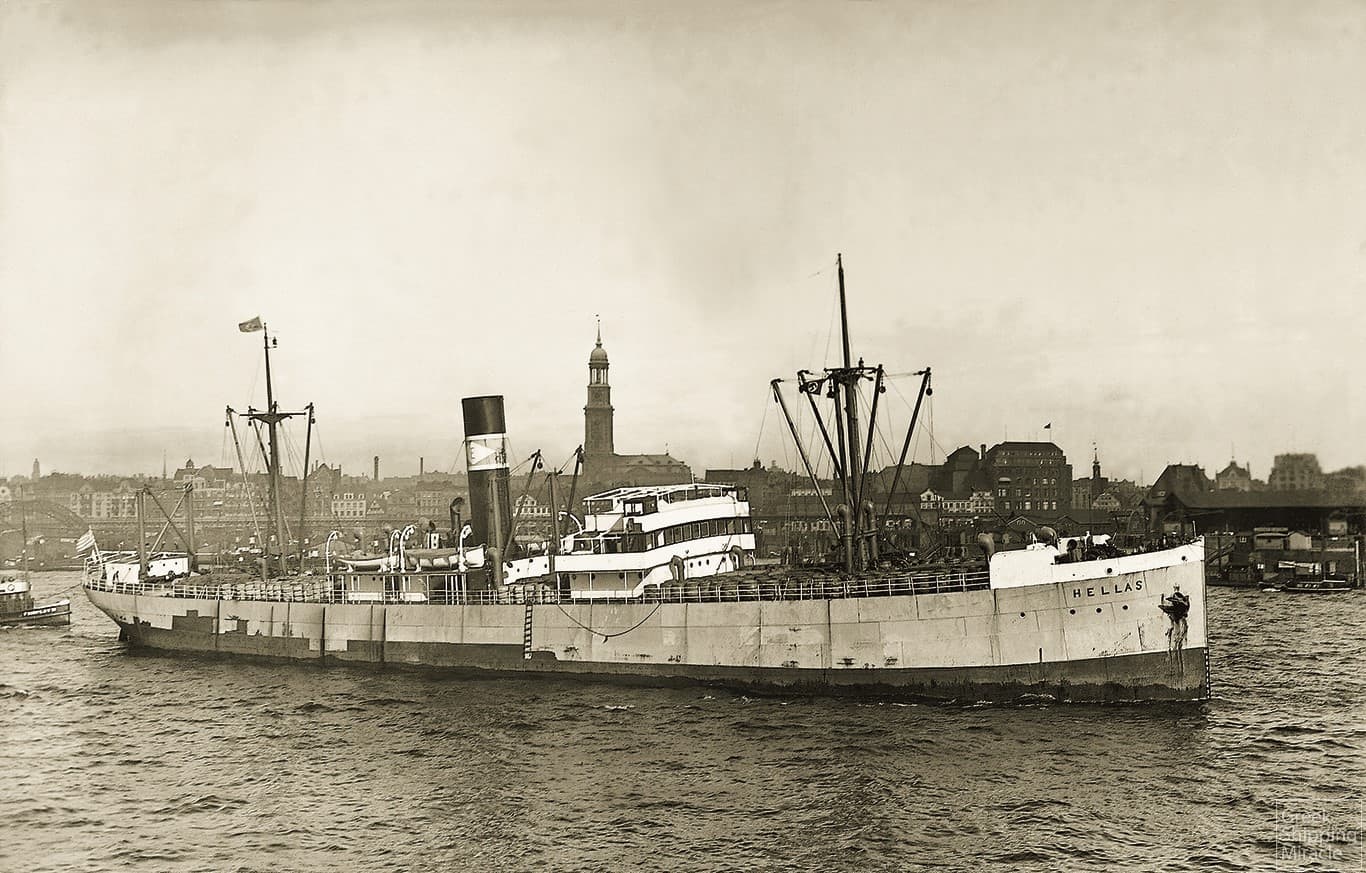

The establishment of Hellenic Lines was announced in 1934, and by the end of that year the first steamer to make up the fleet of the newly established company had been acquired. It was a Swedish freighter, built in 1916 and renamed HELLAS. A few weeks later, a British steamship, built in 1919, replaced the first steamship by the same name, the GRIGORIOS C. II, which had recently been sold for scrap.

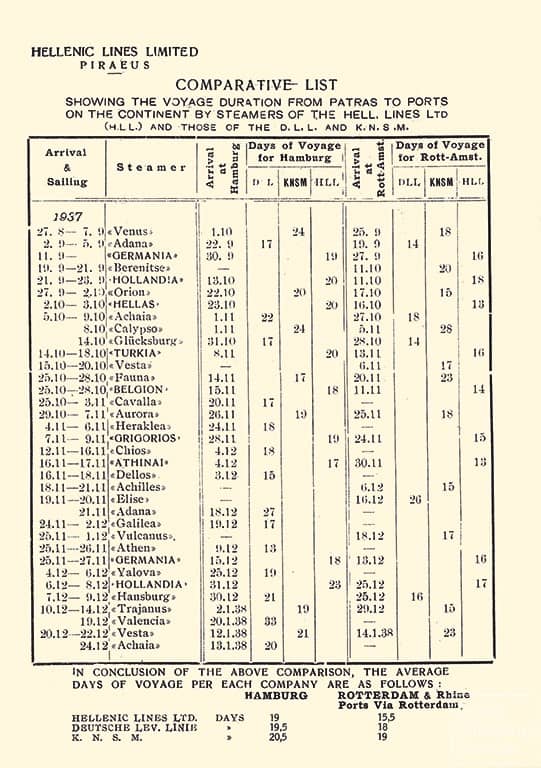

Over the next few years, particularly between 1935 and 1938, the Hellenic Lines fleet was reinforced by six additional steamships, thanks to which the newly formed company was able to make its presence felt, from the outset, in Mediterranean and Northern European liner shipping. At the same time, however, it also experienced a fierce backlash by the coalition of big Northern European companies which now faced the prospect of a new competitor from the Eastern Mediterranean claiming his share of cargo, the transportation of which it had considered its own prerogative for decades.

Without having contributed in the least to the creation of the new company, the Greek state immediately gained significant benefits from its operation. Besides helping to reduce the cost of transporting imported and exported goods and benefiting the national economy by not having to pay significant amounts of foreign currency to third parties to cover the cost of transport, a smooth transfer of military material to Greece was also ensured.

Despite the furious reaction of the Coalition of foreign companies, the progress of Hellenic Lines continued unabated in the years that followed. Its sailings grew more frequent, and any need to increase the shipping business that had now extended across the Atlantic was met by steamships of mainly Greek interest, which were chartered by Hellenic Lines for that purpose. Τhe company used at least 16 steamships in its pre-war voyages, in addition to the eight that made up its fleet.

However, not long after that, World War II broke out in September 1939 and changed everything in marine transport. The Hellenic Lines fleet, managed by its founder, who remained in Greece with his family throughout the war, offered invaluable services with regard to the transport of national cargo until the country was occupied by German forces. At the end of the war, Pericles Callimanopulos, like most of his Greek fellow shipowners, had to start again almost from scratch. The only surviving vessel from the Hellenic Lines fleet was the HELLAS, which happened to be the steamship that had marked the beginning of the company exactly one decade earlier.

Although commercial shipping played a crucial role in national affairs throughout World War II, the Greek state paid very little attention to its post-war reconstruction, since that period coincided with a fierce civil war (1946-49). Having the experience of operating the North American-East Mediterranean line in the early years of the war, Pericles Callimanopulos decided to attempt to rebuild his group based in the United States. He moved there in late 1945, with his family joining him the following year. Greenwhich Connecticut became his new home, and there he stayed until the end of his life. He would commute to his office in New York every day, and on many weekends many of his fellow shipowners as well as Greek businessmen, politicians and artists would visit him and enjoy his and his wife’s hospitality.

In his new place of residence, Callimanopulos also became involved in various social and religious activities. Together with shipowner Captain Nicholas Kulukundis, he headed an initiative to build a new Greek-Orthodox church in the nearby town of Stamford Connecticut. At the same time, he made sure his children attended the best American schools and universities.

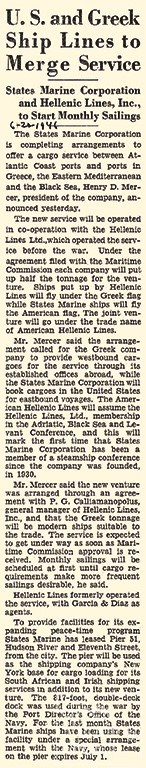

In mid-1946, he entered into an agreement with the US company States Marine Corporation to establish a regular service between the ports of North America and the Eastern Mediterranean / Black Sea. The new line would operate under the name of American-Hellenic Lines and would be served alternately by vessels of each company. Hellenic Lines also applied to the Ministry of Merchant Shipping for the chartering or management of five vessels which had been granted to the Greek government as part of German war reparations. The government agreed to authorise the management of two of the five vessels, the RODOPI and the VORIOS HELLAS, to Hellenic Lines. Around the same time, in the United States, final discussions were under way on the sale of 100 Liberty-type vessels to Greek shipowners. Among those who had applied for the acquisition of a number of ships was Pericles Callimanopulos, who in fact played an important role in the success of this deal which proved crucial to the future of Greek shipping.

In November 1946, Hellenic Lines launched its new North American-Eastern Mediterranean line, co-founded with the States Marine Corporation. This joint venture continued until 20 November 1947 with the participation of five vessels owned by the American company and five Liberty-type vessels owned by the Greek company, the latter five being part of the 100 that were bought by Greeks between December 1946 and April 1947. After the end of the collaboration, the line continued to be operated exclusively by the five vessels owned by Hellenic Lines. Soon afterwards, its fleet was expanded through the acquisition, in public auction, of the two ships which it was already managing, as well as another vessel it acquired through its British subsidiary, the Fenton Steamship Company Ltd.

Despite the constant and persistent efforts of its founder, the company still faced major obstacles in its operation, since even cargo which was to be shipped from the USA to Greece was loaded mainly on US-owned ships. This state of affairs led Callimanopulos to set up American companies, the Transfuel Corporation and Drytrans, Inc., which acquired five US-flagged Liberty-type vessels that were employed in the open market. This parallel business activity continued until 1957, by which time the volume of Hellenic Lines’ business had already grown significantly. Meanwhile, a large shipbuilding program had begun in 1956.

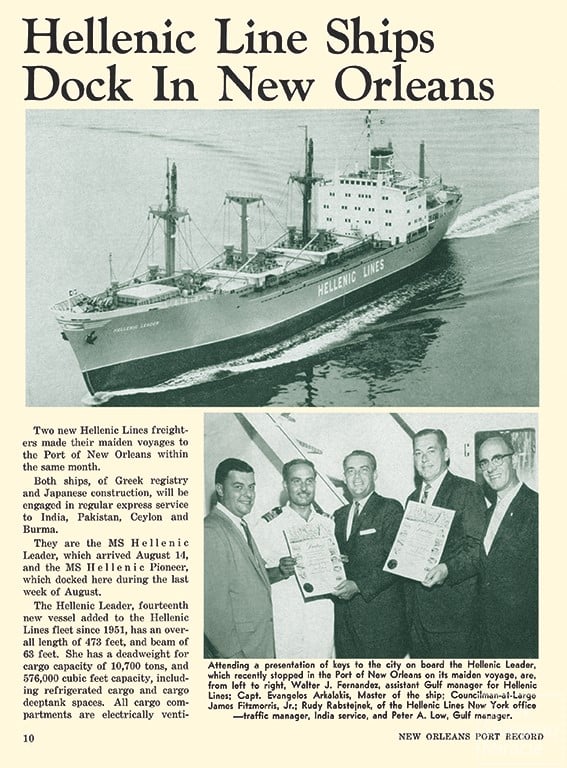

The hostile treatment Hellenic Lines encountered on almost all fronts was not enough to sap its founder’s morale. Throughout the first half of the 1950s, the company expanded its routes by constantly seeking new destinations that would allow it to grow further. By mid-March 1950, it had inaugurated a new route from the ports of the Gulf of Mexico to the Eastern Mediterranean. Furthermore, by taking advantage of the different climate prevailing in the way conferences operated in the United States, it expanded the network of its regular routes beyond the Mediterranean destinations which it was already serving, through the Suez Canal to the Red Sea, the Arabian Gulf, Pakistan, India, Burma, Bangladesh and Ceylon.

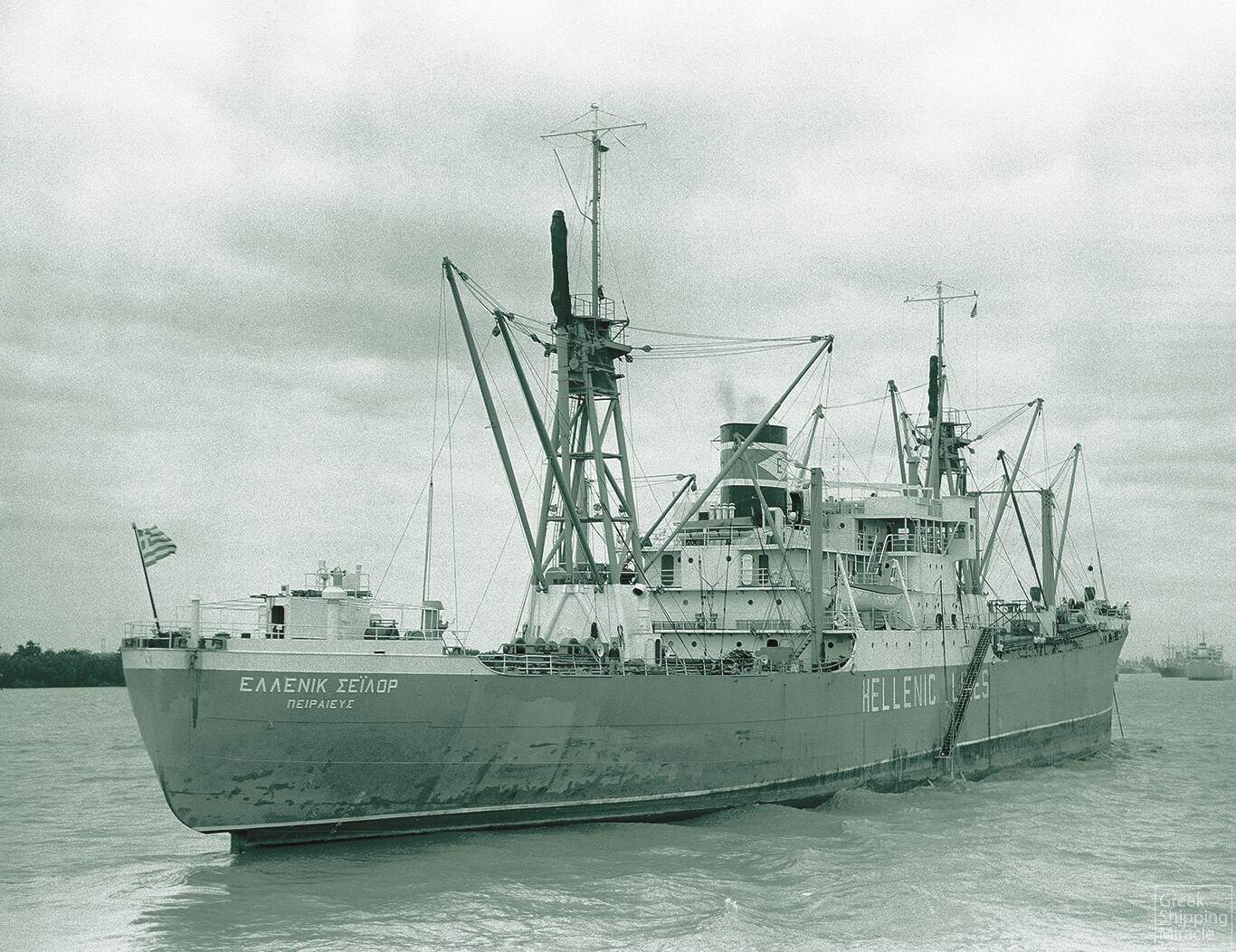

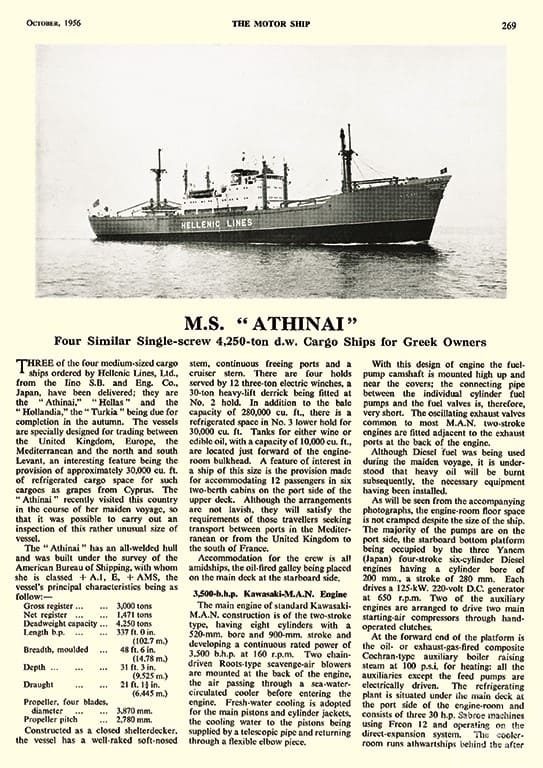

At the same time, owing to its founder’s desire to provide more and more quality services, in addition to acquiring other units from the second-hand market, the company implemented a shipbuilding program, a large one for its time. As part of this project, between 1956 and 1962, 13 newly built ships were delivered to Hellenic Lines by British, Japanese and West German shipyards.

While Hellenic Lines displayed spectacular growth through successive additions of new ships to its fleet, global shipping was already experiencing the side effects of a major crisis. Many ships were being laid up and several shipping companies were on the verge of bankruptcy. Thanks to its involvement in the liner business and the stability of its organisation, not only did Hellenic Lines not have to lay up any vessels, but it continued to grow despite the constant belligerence of its European competitors. In the early 1960s, it launched a new route from the Great Lakes and Eastern Canada to the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Arabian Gulf and India. That year, Hellenic Lines also established the South Levant route, which connected Cyprus to the major port centres of Europe and America.

An important milestone in the company’s development was the purchase of a dock in New York Harbour in April 1962. The dock, which was the largest in the harbour, allowed the simultaneous berthing of up to five ships, enabling Hellenic Lines to serve the ever-increasing needs of its routes.

And while the company was making remarkable progress, enjoying growing acclaim internationally, Greek officials remained unconcerned by the fact that the overwhelming majority of imports and exports were being carried out by foreign ships. This led the company’s management to severely restrict its services to and from Greece, at a time when the needs of the other routes made it imperative to further strengthen the fleet. Thus, during the following years, eight more ships were added to the fleet from the second-hand market. In the late 1960s, Hellenic Lines served its numerous routes with 38 privately-owned vessels.

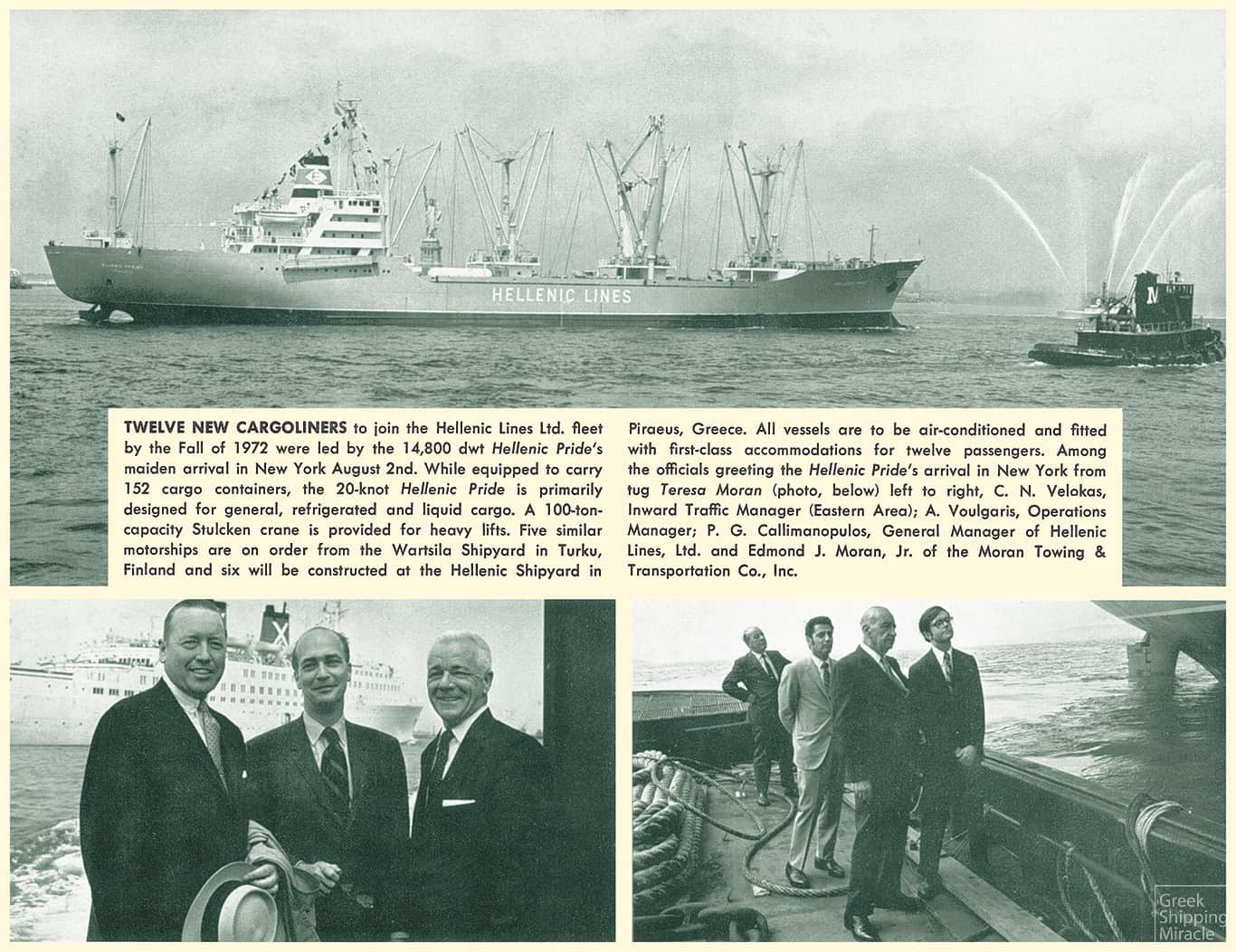

Always looking to the future and despite his advanced age, Pericles Callimanopulos had already decided to radically renew his fleet with new, high specification ships, capable of improving the services offered to his clients and also capable of meeting the demands of growing international competition. In order to accomplish these objectives, a new shipbuilding program was developed. On 18 December 1968, a $30 million contract was signed in New York with the Finnish shipbuilding company Wärtsilä Marine for the construction of six 13,800-ton, 21-knot freighters, which would be delivered from 1971 to 1972. A significant advantage of these ultra-modern ships was that three of their holds would be specifically designed for the transport of containers, an innovation which had already appeared in maritime transport. A few months later, on 31 July 1969, a contract was signed with Hellenic Shipyards S.A. worth $22 million for the construction of six improved, 15,000-tonne and 16.5-knot SD-14 vessels, to be delivered between 1971 and 1972.

Spearheaded by its 12 newly built ships, the company continued a steadily upward course over the following years. In the meantime, significant developments and events affecting his home country prompted Callimanopulos to support the national effort in various ways. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, which forced many Greek Cypriots to flee their homes, led to the decision on the part of Hellenic Lines to transport aid for Cypriot refugees free of charge. In addition, the company also incurred the cost of placing this cargo in containers for safe transport.

In mid-1977, Pericles Callimanopulos visited the Minister of National Defense of Greece Evangelos Averoff and handed him a cheque for $400,000 in support of the Hellenic Navy. This amount, which corresponded to the cost of building a patrol boat was added to the account created to cover the cost of building six ships of this type, to be constructed at Hellenic Shipyards S.A. for the Hellenic Navy.

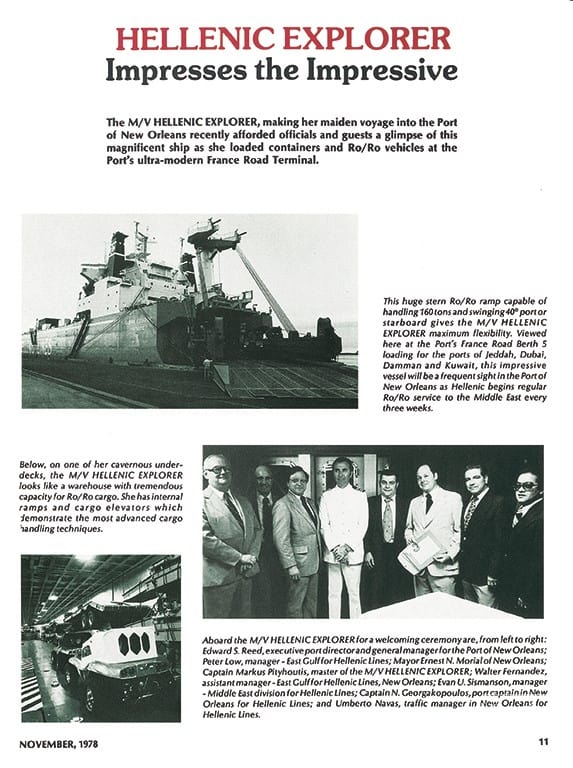

It was already known at the time that Hellenic Lines had placed an order with Japan’s Sasebo Naval Arsenal shipyard for the construction of roll-on/roll-off (RORO) ships, designed to carry wheeled cargo and containers. The order was for three ships worth $18.5 million each, to be delivered in 1978. This initiative signaled the company’s move into container ships, which had begun to take over cargo routes, pushing out conventional freighters.

In late 1978, Belgium awarded Pericles Callimanopulos the Order of Leopold II for the services the Hellenic Line ships had provided for more than 40 years to Belgian commerce via the port of Antwerp. It was one of the many high honours he received in his lifetime from Greece and other countries. One year later, on 20 September 1979, Pericles Callimanopulos died while at work in his New York office – exactly as he had said he wished to pass away.

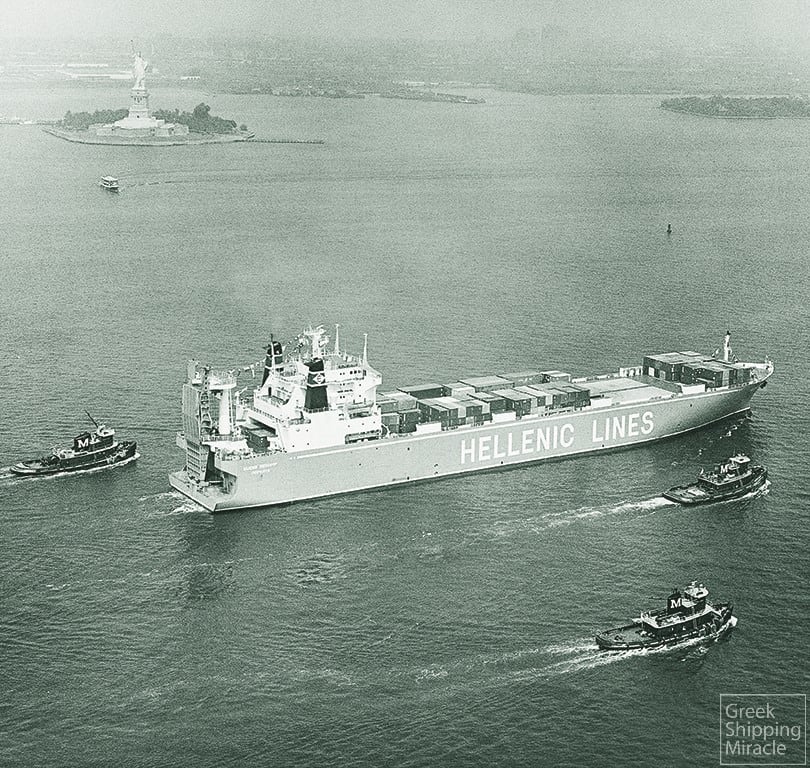

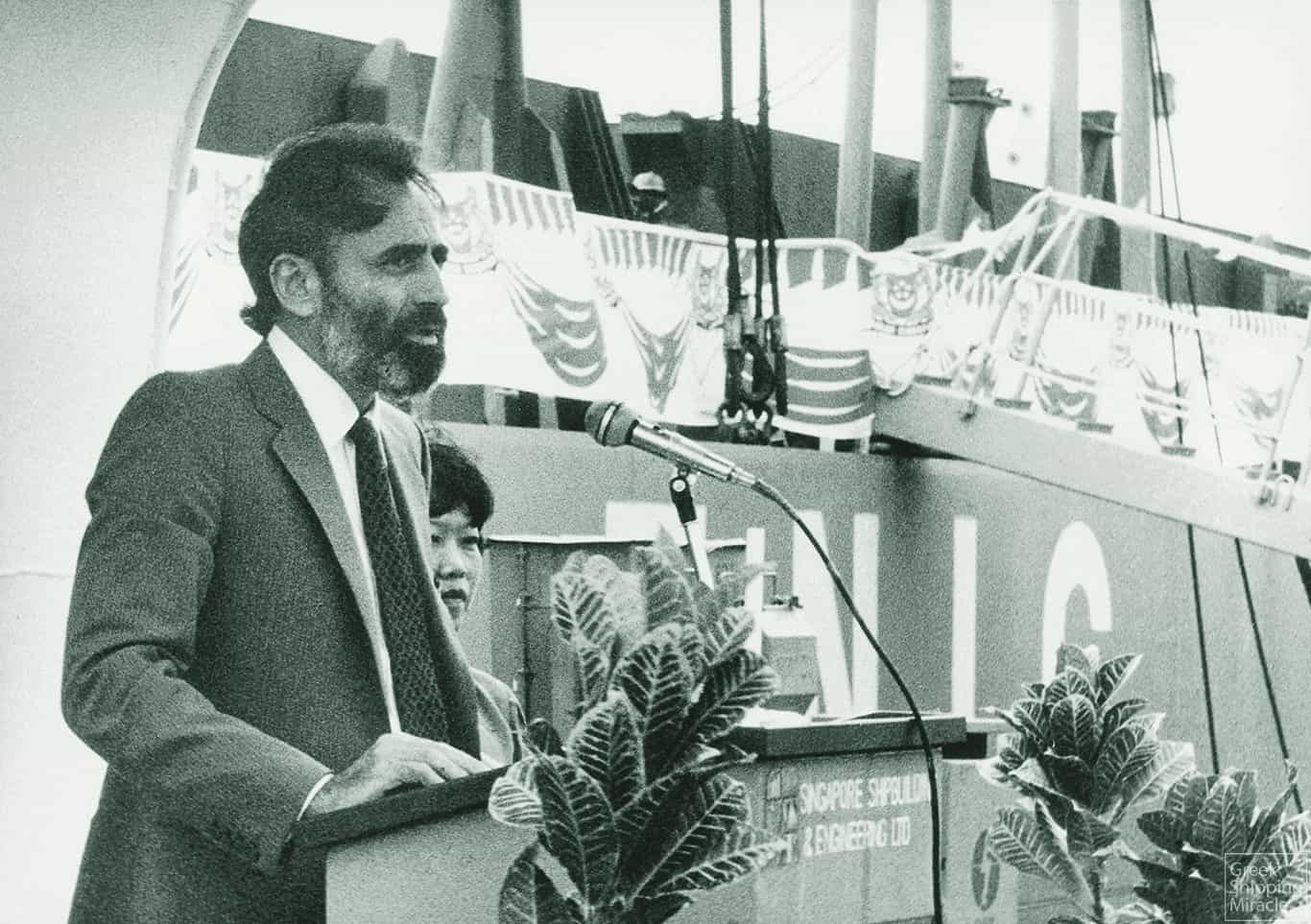

On 2 November 1979, the position of managing director of Hellenic Lines was assumed by the son of its founder, Gregory P. Callimanopulos, who had run an independent business, Trade & Transport Inc., since the mid-1960s. The new head of the company followed the strategy his father had set out, with the aim of modernising the fleet and gradually changing the company’s profile to one dealing exclusively in container ships. Accordingly, three vessels of this type were acquired from a French company, and an order for the construction of three such ships was also placed with Singapore shipyards. These were delivered in 1981 and 1982. An important step in completing the transformation of the fleet was also the conversion into full cellular containerships, at the Italian Cantieri Navali Riuniti SpA shipyards, of four of the six cargo ships which had been built in Finland in 1971. These were delivered in 1983.

With the aim of further strengthening its containership fleet to meet the ever-expanding needs of its routes, Hellenic Lines had already acquired two more second-hand vessels of this type in 1982. Within a short time, the company had made a huge step towards fully modernising its fleet with container ships. This change was at the time imperative not only for the survival but also for the development of any liner company. Hellenic Lines had acquired 15 ships, which it had managed to integrate into its fleet in the same way it had advanced for nearly half a century – under its own strength alone. But it was under this same strength that it would now have to face a new, formidable opponent, which was much tougher and, crucially, more unpredictable than the closed conferences: a major crisis – the biggest since World War II – affecting international shipping.

In October 1983, the sharp drop in oil prices adversely affected the Arabian Gulf market – the core of Hellenic Lines’ activity. At the same time, the global shipping crisis was worsening day by day, causing hundreds of ships to be laid up. At the same time, in an interview to an American magazine, the new head of Hellenic Lines, Gregory Callimanopulos, described the situation as “blurry”. He went on to express his concern about the emphasis placed on the construction of large ships, in combination with the fact that the cargo that would justify their construction did not exist. He compared this phenomenon to that of the previous decade involving tankers, and argued that the best market at that particular time was the one his company did not serve, namely Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia in general.

With the global shipping crisis deepening and in the face of growing problems with all their clients, international banks had begun to take drastic action. In early December 1983, Hellenic Lines’ creditors, who had financed part of its large investment plan, presented insurmountable demands that the company was unable to meet. Unlike most liner companies which were backed by their home governments and their traditional bankers, Hellenic Lines was literally left to its fate. At the most difficult moment in its history, it received absolutely no help. It was faced with the harshness of its traditional financiers who, while supporting other European companies, did not deal with the group’s difficulties with the same understanding. Even though Hellenic Lines asked for it, it did not receive the slightest support from the Greek state either, whose name and flag it had honoured and carried across the globe for half a century. This marked the end of a major company which, throughout its existence, was a model for how private initiative can develop significant international activity without state subsidies or other protectionist measures.